Choice, made problematic

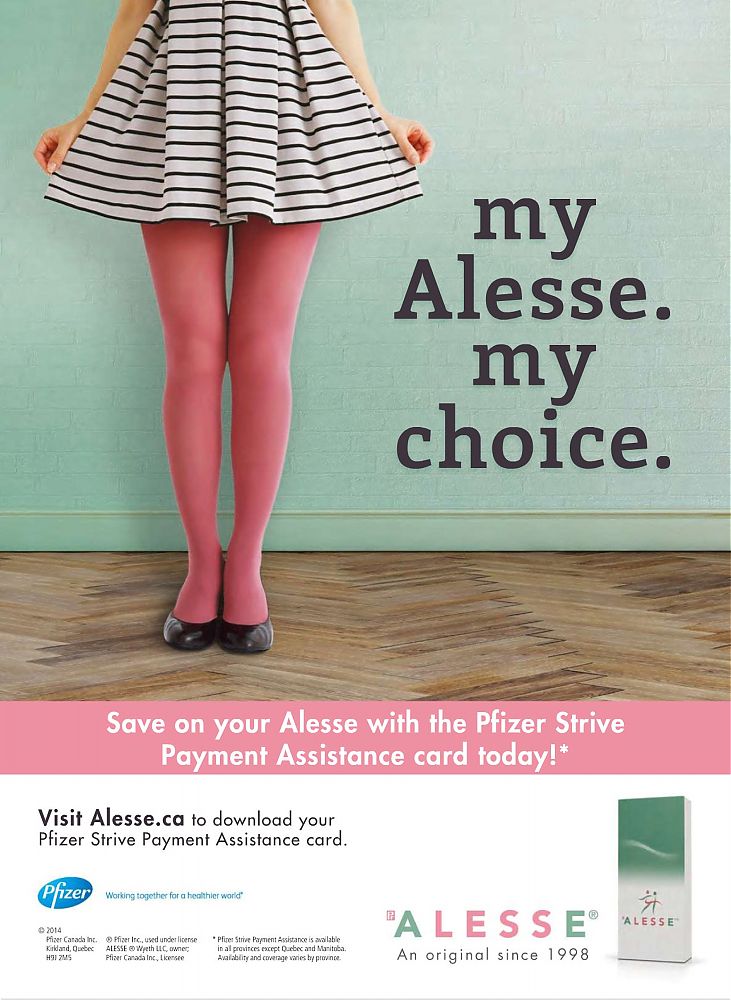

The original Alesse ad.

Pfizer has advertised birth control drug Alesse to Canadian women for years, even at UBC, as student Natalie Morris (2017) notes. In this ad, Canadian women receive yet another dose of messaging about their reproductive health. It features a photo of the lower half of a nondescript woman’s body, with her unique personality conveyed through bright stockings and a striped skirt. Her light skin tone indicates that she is white. To the side, bold text transmits the ad’s key message: taking Alesse enables women to take control of their reproductive health by choosing when pregnancy is appropriate for them. The pastel colour scheme perhaps conveys a sense of freshness, but the ad has unintended side effects: the underlying message perpetuates ongoing problematics with women’s reproductive health in Canada.

The increased marketing of birth control products in Canada has been accompanied by choice-centred language, leaving dangerous implications for women. As Ford and Saibil (2010) suggest in their description of Canadian reproductive medicine in a contemporary neoliberal context, “concepts such as choice and empowerment, language used by feminists to describe specific goals, are co-opted and distorted to mean personal responsibility for preventing or managing disease” (p. 10). In this ad, the wording “my Alesse. my choice” places the burden on Canadian women to protect their own health, failing to mention the “feminization of poverty” (Ford & Saibil, 2010, p. 9) caused by a trend of states retreating from social safety nets. The World Health Organization’s (2015) structural determinants of health model argues that states and transnational organizations must address societal contributors to health, such as education and poverty, to improve the well-being of individuals. This holds especially true for racialized or otherwise marginalized women, invisible in this ad, who face increased structural barriers to health. This ad offers a window into the neoliberal Canadian phenomenon where marginalized women are increasingly tasked with defending their own reproductive health in the face of lacking governmental support.

Jamming the blame

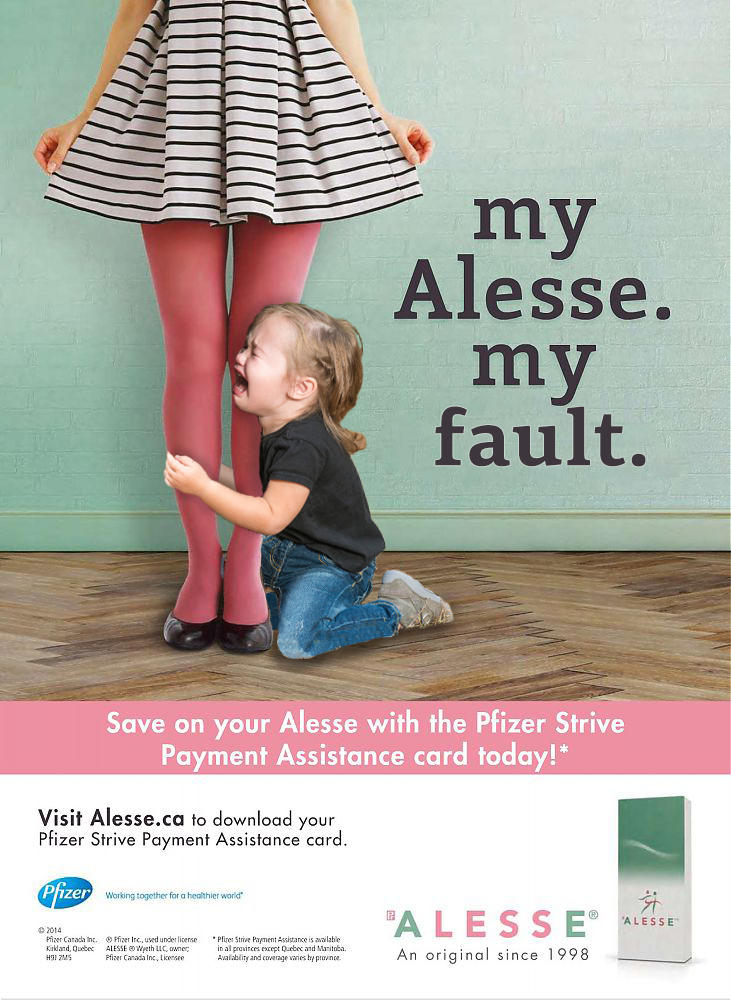

The jammed ad.

With crosscurrents of structural determinants and individual reproductive health in the ad, I aimed to exaggerate the alarming effect that choice-centred language has on shifting the responsibility of women’s reproductive health to women themselves. A significant change I made was the replacement of the phrase “my choice” with the more sinister “my fault.” While the ad encourages women to purchase Alesse to empower their health decisions, Ford and Saibil (2010) assert that women’s choices among birth control options are “seriously constrained by social policies and societal structures that underlie the determinants of health and well-being” (p. 10). The absurdity that women can choose to transform their health landscape through the small act of taking a brand of birth control without any governmental action is made clear by removing the word “choice,” and if women choose not to take the pill, it is their “fault” for being irresponsible. The reality remains that women are encumbered with having to fend for their health, particularly marginalized women who often lack access to culturally sensitive birth control. In a push to sell more medication, Pfizer’s reductionist framing obscures the role government policy plays in supporting structural determinants of Canadian women’s health.

The other alteration I made was the addition of a crying child clinging to the woman’s legs. With the ad’s peaceful colouration as a backdrop, I intended for the child’s acute distress to disrupt Pfizer’s narrative. The child represents the burden Canadian mothers face of maintaining both their own and their children’s health, with structural determinants contributing additional hardship. Further, the child’s emotion represents the unmet need of marginalized families for this very structural support. Morris (2017) writes that Alesse ads call on women to purchase the branded drug over its cheaper generic forms. For women experiencing poverty, affordability challenges with putting food on the table and caring for children are only exacerbated by this harmful messaging. Through these changes, I highlighted that the reality of women’s reproductive health is complicated by structural health determinants and neoliberal individualism, something that the advertisers may find a tough pill to swallow.

References

[Alesse ad]. (2015). Adpharm. https://adpharm.net/_Alesse_brand.htm

Ford, A. R., & Saibil, D. (2010). Introduction: The steering committee of women and health protection. In A. R. Ford & D. Saibil (Eds.), The push to prescribe: Women and Canadian drug policy (pp. 1-13). Women’s Press.

Morris, N. (2017, October). Op-ed: A little less Alesse, please. The Ubyssey. https://www.ubyssey.ca/opinion/A-little-less-Alesse-please/

World Health Organization. (2015). Health in the post-2015 development agenda: Need for a social determinants of health approach. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/advocacy/health-post-2015_sdh/en/