As I mentioned in this previous post, I am working through feedback from my students. All quantitative data, as well as links to all previous blog posts (since 2011), are available here. ALERT! This post has become extra ridiculously long. Writing it is helping me think and process this overwhelming year, so I’m just going with it.

Last round I focused on PSYC 217 Research Methods. For this installment, I focus on PSYC 218 Advanced Statistics for Behavioural Sciences, in which I have taught over 1000 students across 11 sections since 2012. Like 217, it’s a required course for BA Psychology Majors. I regularly teach this course in Term 2 (January start), two sections back-to-back of about 100 students each. This post will focus on my W2019 Term 2 results (which started in January 2020 business as usual, and pivoted in a state of emergency to remote learning). It will then compare with results from my mid-pandemic January 2021 fully online offering. I’ll start with an overview of what changed across these offerings, as well as within the 2020 offering during the pandemic onset.

Both years’ iterations featured the same Learning Objectives and broad approach (compare syllabi here and here). As is true in all sections for the past 10 or so years, both iterations featured a series of assignments with real data collected during the term from student activities. These assignments were handed in and graded online, as usual. Both iterations featured three tests and a cumulative final exam. In January 2020, these tests started out as Two-Staged, but I abandoned that practice once the pandemic hit as I couldn’t figure out the logistics. In January 2020, I started out using iClickers during each class (as I’d been doing for years) and after the pivot I kept the questions but didn’t attempt to record results — those participation points were considered completed. By January 2021, I learned to quickly create a “quiz” in Canvas that students could use to respond to clicker-style questions (even if they were joining asynchronously). As always, many students approach this course with trepidation, often after having identified as being “bad at math” — sometimes holding tight to this identity for decades. Anxiety management is a regular part of my teaching practice in this course. Let’s just say anxiety was, ahem, heightened in both of these years.

******My memory of the emergency pivot at the onset of the pandemic, because apparently I need to write this******

UBC didn’t officially close campus until end-of-day on Friday March 13, 2020, but rumours started circulating a couple of days before. On Wednesday or Thursday of that week, I hosted an impromptu (f2f!) session with colleagues to share what little I knew about pre-recording and uploading videos in Canvas — I’d given a talk in Florida at the end of January (including being on the last flight from Vancouver to Toronto that had started in Shanghai, the epicentre), and had learned some basics of using Camtasia to record a lesson with pauses for clicker questions. By Friday morning, I had already announced to my students that they were welcome to stay safe at home and watch the recording instead. A handful of students arrived, maybe half dozen each section, and I stood at the door and handed out disinfectant wipes for students to wash their desks and chairs. We didn’t know then that COVID was primarily passed through the air, so no one had masks. I remember leaving my office that afternoon after receiving that official email of the closure, not knowing when I’d return, grabbing everything I could carry home with me on the bus. I remember when I was getting off the bus, the driver was remarking to someone how unusually empty it was, and I chimed in that UBC had just closed because of the pandemic. It was news to them. Turns out, I have visited my office just twice since that day (late March and August), both times for 30 minute visits to grab what I could carry. This is the longest I’ve been away from UBC campus since I started as a graduate student in Fall 2003.

I had exactly one weekend to figure out how to teach my students statistics online, and I knew pre-recording everything wasn’t going to work for me. I chose live synchronous classes using Collaborate Ultra (CU), because it was FIPPA-compliant and already integrated into my Canvas course so I didn’t have to direct students elsewhere or figure out how to save and upload the videos for those who needed to watch later. I don’t have a home office, so I perched at my dining table in our open-concept space, overlooking the galley kitchen, living room area, and modest balcony. I’ve been working there ever since. Because of bandwidth concerns, and how CU is set up, I never saw most of those students’ faces again. That was heartbreaking.

When I reflect back on that time, I think of it as a time of terror and chaos and confusion, which translated into about ten million emails. My heart broke daily to hear my students’ stories and anxieties poured out in my inbox, and especially those who were waiting for my permission to book a flight to home before the borders closed. My answer was, of course, a resounding yes — we can figure out how to solve their absence later. They needed to stay safe. I remember at least once a student who joined class from a lineup at an airport, which drove home how desperate students were, but also how much I just needed to keep teaching. That hour to focus on statistics was an island of distraction for some students, and for me too [yup, I’m crying now… like I did most days of 2020… shout out to my husband for going through all this alongside me]. We were all in panic for our safety — grocery store shelves were emptied, we were afraid to leave our homes at all, insomnia was rampant. I also remember the community of colleagues that strengthened on Twitter during those early days. We posted threads of support and ideas, like what it was like to give an exam online using different features and settings, so other colleagues could learn from what happened. We shared resources and advice in a flurry — I probably spent as much time on Twitter as anything else, and that was such important, vital time. Thank you to my husband, my students and my Twitter community of colleagues for being a life raft in those early days.

************************

Although the plan for January 2020’s offering had started out business as usual, by the end of the term, everything post-March 16 became optional. Some students thrived (relatively speaking) during this time, but many were crippled by anxiety, fear, emergency travel, and general chaos of living through the terrifying onset of a pandemic. Policy changes at the UBC and Faculty of Arts levels opened the gates widely for late withdrawals and other accommodations. I and my colleagues worked hard to translate those policy changes at the Department and course level to support our students as best we could. Ultimately, our PSYC 218 teaching team agreed to ample accommodations, including essentially treating the last third of the course as optional. Implementation details were a bit different across sections; see Syllabus 2020 Amendment 2 Options for End of Term PSYC 218 001 and 002 for where mine landed.

By the time I was preparing my January 2021 offering, I had already taught two entire courses during a pandemic. I also had the experience of teaching the last third of this very course online during the emergency pivot. Both of these sets of experiences made this course an extra emotional one, due to exhaustion and memories of panic. But also, I and the students were much more fluent in all the technologies and how to run/manage class time, which made the logistics easier. Rather than making many changes, like I had for PSYC 217 in Fall term, I kept my PSYC 218 course as similar to “business as usual” as I could. But I layered in lots of flexibility in deadlines, as well as the option to customize the weighting of some course assessments; see the syllabus for more details on assessments and policies. I also switched over to Zoom, as it was now integrated in Canvas and FIPPA-compliant. This change made it possible to see some of my students’ faces every class period — which made an immeasurable positive difference to my well-being and enthusiasm each day. I remain so grateful to those students who chose to turn on their cameras.

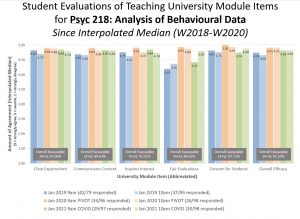

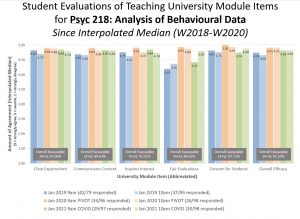

So, with this lengthy backdrop in mind, let’s begin exploring student feedback! I’ll start with quantitative results. As shown below, response rates have been down since the pandemic began. The year before all this (W2018 Term 2, starting January 2019), my response rate was 44%. Since then, the response rate has been 31% (just after the emergency pivot 2020), and 30% (this past term). I’m actually surprised it’s stayed this high, as I can’t offer class time in the same way I used to do (folks just exit, whereas in The Before Times everyone in attendance would remain seated with a kind of social norm present to complete them).

Because the response rate has dropped, it is tough to compare data from The Before Times to after. Aggregate ratings from 2020 and 2021 appear a bit higher than 2019, but given the response rate, it’s possible that the folks with the less positive attitudes simply didn’t respond. But the big picture is that the numbers are (remarkably) not all that different. The one exception is Fair Evaluations. Since the pandemic, I cut Two-Stage tests (which were identified as a source of challenge in PSYC 217), and offered more time for tests, as well as more flexibility and choice. Fair Evaluations item was exceptionally high in 2020, likely owing to the tremendous flexibility from the pandemic pivot onward (basically, if you submitted something, it only counted if it improved your grade, but you didn’t have to submit anything else–a decent proportion of LOs were already measured by then). 2021 ratings were also higher than The Before Times, which could have stemmed from lack of two-stage tests (while keeping the full period of time for relatively few test questions), and/or offering the ability to customize how much the tests, final exam, and other components were worth. When we go back, I’ll likely reinstate two-stage tests, but continue the customization options and flexibility. If dropping two-stage tests was driving this perceived (relative) boost in fairness, that item should drop back to its former level.

Qualitative data time! This is always an emotional and difficult undertaking for me, which is why I start with quant to orient me to what I’m looking for. I have 7 pages to work though for 2020, and 6 pages for 2021. I try to roughly code student comments into four quadrants along two continua (thanks to Jan Johnson for teaching me this strategy about a decade ago). The first is valence (positive-negative) and the second is ‘under my control, changeable’ on the one end, and ‘not under my control or not willing to change’ on the other. ‘Not willing to change’ is usually because I have data behind that decision (but I might rethink implementation) or it’s just not possible given the time-effort that I have to give in the context of my other commitments. It’s also pretty common to read evaluations that directly conflict with each other (I loved this! alongside I hated this!), so I need to look for common themes.

Key points from January 2020 offering qualitative data. At the risk of sounding boastful, I must admit that, by far, the most frequent comments were about positive qualities I brought: #1 care and compassion (especially during COVID but also before), #2 enthusiasm and passion, #3 fun and engaging and participative (often with caveats like surprisingly, for statistics; even when moved online), #4 encouragement and support. I appreciated the specific things various people identified as helpful: weekly announcements including wellness moments, lots of resources and tips, well-considered syllabus and pacing, I was available and responsive, recorded lessons, two-stage exams, lots of in-class participation, thorough preparation and organization, fair assessments that broke the course up in manageable ways (even if it looked like a lot at the start). One person noted the helpfulness of studying from explicit Learning Objectives, and another remembered I brought granola bars in case they hadn’t had breakfast. I think one bigger lesson here is that lots of little touches I’ve added here and there over the many years of teaching can add up to many opportunities to reach one more student. I’ve been teaching my own courses since 2008. This didn’t happen overnight. Each of these additions came from reflective practice, listening to my students, reading evaluations carefully (trust me, they weren’t always this positive), going to teaching-focused conferences/workshops and learning from colleagues, staying open to change, and persisting through incremental change given the capacity I had that term (especially when my dreams were bigger than what I could reasonably offer at the time).

To be honest, there weren’t too many strong themes emerging from the negative side, but each of these were identified by 2-3 people: expensive (especially SPSS — but now as of 2021 that’s free thanks to UBC!), wanted more time for the individual portion of the two-stage tests, desire for practice tests *with* time pressure. One person noted that my energy and reassurance was “just too much” sometimes, but given those qualities were major themes that lots of people found helpful, I can’t dwell on this. Can’t be all things to everyone.

Some example comments:

“She does her best to create the best learning environment for students, with lots of opportunities for connecting and applying ideas. She teaches a tough subject but makes it very easy to understand and having her as a teacher helped me achieve a lot this semester.”

“Dr. Rawn stepped up and illustrated an incredible amount of compassion, consideration and honestly, love for us during the pandemic. She illustrated how much she cared about us and treated us as humans rather than just students. Words aren’t enough.” — I admit, this one made me cry

“Encouraged an environment of learning and encouraged everyone to push their boundaries. Showcased care, affection and concern for every student and was very involved and helpful to anyone who wanted the help.”

I was surprised that there were no comments whatsoever about the technological choices I made in that frantic flurry, choices that seemed so important in the moment. Like many faculty thrust into emergency online teaching, I agonized about and spent countless hours learning and choosing and implementing and troubleshooting various technologies. Was the tech simply not salient in hindsight… because I put in that time and energy so they went reasonably well? Or did all the technology issues fall away, taking a backseat to the feelings of compassion, care, enthusiasm (despite our circumstances), and sense of common humanity it seems I was able to convey? As I concluded in my last post, we teach students, not topics or courses. I’ll add here that we teach students, sometimes through technology and sometimes despite the limitations of technology. What matters is not the specific tool, it’s how we’ve used it to reach and support the human beings, learners, students, who are looking to us to light their path.

[On returning to writing: I’m returning to finish this after almost a month away from this post. Along with taking some time off, and responding to a surprising number of emails, I’ve been doing a fair amount of reading (highly recommend Oluo’s So you want to talk about race, Morton’s Moving up without losing your way, and Bear & Gareau’s Indigenous Canada). Sometimes I need to write, and sometimes I need to read.]

Key points from 2021 qualitative data: These data indicate that the course went very well in the eyes of most respondents. Most comments could be grouped like this: (1) feeling my concern for students and their learning, for example through accommodations and flexibility, encouragement, and using student feedback; (2) clarity, strong organization, and preparation that helped scaffold learning and keep people on track; (3) fun and engaging, despite the difficulty and high standards; (4) I brought passion, enthusiasm, and encouragement. Negative comments were hard to code, as they tended to be fairly idiosyncratic. Four people wanted more straight lecture with less participation and/or breakout groups. Four people mentioned tests in a negative way: two people requested more — and more challenging — practice tests; two people requested more questions on tests (so each is worth less). For comparison, four people mentioned tests in a positive way: they were applied (rather than drills or memory), fair learning assessments, and appreciated the extra time I gave. Again, comments about the technologies were largely absent. Two of my favourite comments:

“I was very afraid of this course for so many reasons but Dr. Rawn has been absolutely amazing and I genuinely wouldn’t have been able to achieve what I have and learned this much if it wasn’t for her. She is so incredibly caring towards us and does (way too much) work just to help us! The lectures were always engaging and participation was encouraged. The switch to online learning seemed flawless (although I know it wasn’t) and she was always so well prepared and laid everything out for us in a way we could understand. Also I loved the autonomy given to us by being allowed to choose our weighting for certain marks. I cannot thank Dr. Rawn enough for this semester and how much she helped in terms of this class but also be a positive part of my life during these sad times.”

“PSYC 218 is not an easy course but having Dr. Rawn as the instructor made things a lot more bearable. She is passionate about the topic and that is transmitted through the classes to students. She goes the extra mile with her teaching, implementing strategies such as the Self–Determination Theory so that her students feel more engaged with the

course and it is definitely working. Furthermore, her analogies, i–clicker questions and examples are incredibly useful. A lot of the things she implements are things that I would love to see other teachers doing as well. But what I like the most about her is the transparent and effective communication she has with her students. She actively seeks feedback

and that is why she knows how her students are feeling, she makes us feel understood and supported.”

Thank you so much to everyone for your time and engagement with this feedback process!

Next time on the blog… I reflect on student feedback and my experiences in PSYC 417 Advanced Seminar in Psychology of Teaching and Learning, which was the very first course I taught fully online, back in July-August 2020. (Note that course code is changing to PSYC 427 for 2021, and I’ll teach it in Winter Session Term 2.)

Follow

Follow