March 21st, 2012

BY Nicholas Choy & Caroline Chiu

Political Origin

In dealing with Singapore’s fast-growing motor vehicle population prior to 1990, several regulations such as road tax, import duty and registration fees were implemented (Tan, 2001). However, rising GDP allowed these costs to be affordable and an increasing number of vehicles on the road led to traffic congestion, which increases energy use, and air pollution (APEIS and RISPO, 2005). Since taxes on usage were inadequate a quota system was implemented to limit the quantity of cars. Effective in May 1990 the Vehicle Quota System (VQS) utilized an auction system to allow market forces to allocate permits for owning cars thereby reducing environmental externalities (APEIS and RISPO, 2005).

Timeline of Major Changes and Design of Vehicle Quota System (VQS)

May 1990 – Implementation of VQS

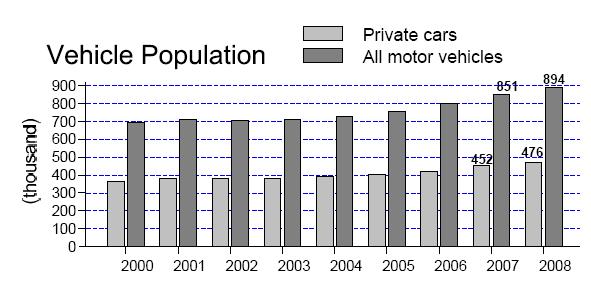

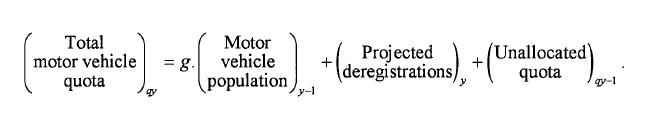

The objective of the policy was to maintain the growth rate (g) of Singapore’s vehicle population at 3% based on the total number of cars on the road (Tan, 2001). The public

The public

Currently, Singaporeans who wish to purchase new vehicles must first successfully win a bid for a Certificate of Entitlement (COE) which is subsequently assigned to a specific car and is valid for 10 years. At the end of this period, the owner may choose to renew the COE for another 5 or 10 years at the prevailing quota price (APEIS and RISPO, 2005). If the car owner chooses to sell the car before the period is over, the remaining life span of the COE would be transferred along with the car to the new owner (Tan, 2001).

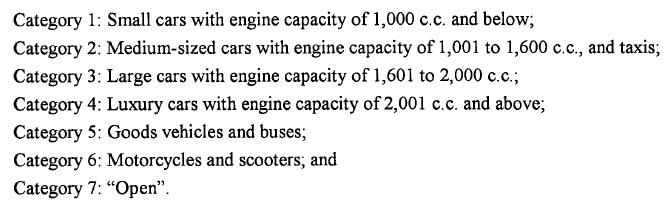

At the inception of the VQS, bids were placed according to vehicle categories which were based on engine size and type. Sealed bid auctions were held monthly and each person was allowed to bid only once per period. A bidder was also required to submit a deposit equivalent to 50% of their bid price (APEIS and RISPO, 2005). For example if 100 permits are granted for a category, then everyone who bid below the 100th highest bid price would fail to obtain a COE. The successful 100 bidders would pay the amount of the 100th highest bid (Tan, 2001). At first COEs were transferable as long as they had not been used to purchase a new car (Tan, 2001). This created a secondary market which allowed the price and allocation of quotas to be determined by willingness to pay; a mechanism that overcame the uncertainty caused by sealed bid auctions.

At first COEs were transferable as long as they had not been used to purchase a new car (Tan, 2001). This created a secondary market which allowed the price and allocation of quotas to be determined by willingness to pay; a mechanism that overcame the uncertainty caused by sealed bid auctions.

Mid-1991

However, the secondary market created incentives for rent-seeking speculators, who had no intention of using the permits, to bid up the price and hoard the COEs. The public blamed speculation on transferability pushed quota prices to an “all-time high”; so, non-transferability was intended to stabilize quota prices (Tan, 2001). Since then, the policy was revised so that permits for categories 1-4 and 6 could not be traded within 3-6 months of the winning auction and had to be assigned to a new car within that time frame. Thereafter the quota essentially became a part of the car’s value and could be transferred if the car was resold but was subject to a levy of 2% of the car’s value.

1999 – Sub-categorization (Santos, Li and Koh, 2004)

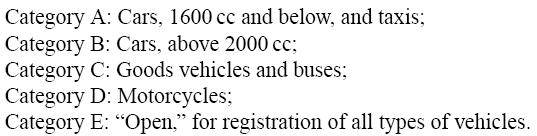

The original categories were changed to counter the regressive effects of the policy. Theoretically, low-income groups and high-income groups bid in separate auctions so as to not force low-income buyers out of the market (Santos, Li and Koh, 2004).

The original categories were changed to counter the regressive effects of the policy. Theoretically, low-income groups and high-income groups bid in separate auctions so as to not force low-income buyers out of the market (Santos, Li and Koh, 2004).

2009

Government reduced the annual allowable growth rate from 3% to 1.5% due to the realization of the slower expansion in road infrastructures (Saad, 2011).

Results

The VQS has seen successes in meeting its target of limiting the growth of vehicle population to 3%

While other cities of similar development log average vehicle speeds of ~15km/h Singapore’s average speed of ~30km/h (APEIS and RISPO, 2005). The greater rate of traffic flow and increase in average speeds can lead to 50% more fuel consumption. In 1998 Singapore’s per capita energy consumption from road transport was 0.29 tons of oil equivalent (TOE) compared to 0.69 in Germany and 1.75 in America (Ang and Tan, 2001) As for air pollution, some pollutants may have increased, but overall, all pollution levels are within the standards of EPA and WHO (APEIS and RISPO, 2005).

Although the auction system is easy for the government to administer, the sub-categorization which was meant to protect the less wealthy created regressive effects (Koh, 2004) . In 2000 the COE of $36,684 for a Toyota Corolla contributed to its final selling price of $87,438. Whereas the COE for a BMW 523i amounted to $37,001 as part its final selling price of $234,000 (Ang and Tan, 2001). While an auction system can be efficient in establishing a price that equates perceived marginal benefits to costs, the differentiated categories built clumped the demand for those with less ability to pay (small vehicle category) to drive up quota prices relative to the price of cars. Studies on the effects of the non-transferability of permits on social welfare do not give a clear-cut picture. But this could serve the policy’s goal of limiting the total number of cars. Since the permit essentially becomes a part of the car, transferability occurs through the used car markets and are subject to environmental inspections. Since COEs expire, the car population should be newer relative to other countries. This should disseminate more fuel efficient models as technology and standards improve. However the existence of the Open Category, which was exempted from the non-transferable clause, reduces social equity. Successful bids in this category can be used to purchase vehicles in any category and was implemented to improve the “allocative flexibility” (Koh, 2004) of the system. A large proportion are applied to large and luxury cars.

Conclusion

While the VQS is comprehensive in its application to all agents who own vehicles it is not cost minimizing and contributes to social inequity. Rising prices from the reduction of quotas have been accompanied by a large increase in the used car market. By 2003 the Singaporean government raised $23 billion from 156 auctions which it reinvested into transport infrastructure (Koh, 2004). The benefits from the provision and utilization of public transport from quota rents reinforce the VQS’ success in reducing the negative externalities from traffic congestion. One group which has benefited from the policy is the car dealers (who largely drove speculation in 1991) and profit from the used car market.

.

References

Ang, B. W., & Tan, K. C. (2001) Why singapore’s land transportation energy consumption is relatively low – Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2001.tb00755.x/pdf

Asia-Pacific Environmental Innovation Strategies (APEIS), & Research on Innovative and Strategic Policy Options (RISPO). (2005). Strategic Policy Options: Introducing Number Plate Bidding Systems. Asia-Pacific Environmental Innovation Strategies (APEIS), & Research on Innovative and Strategic Policy Options (RISPO). Retrieved from enviroscope.iges.or.jp/contents/APEIS/RISPO/spo/pdf/sp4206.pdf

Koh, T. H. (2004). Congestion control and vehicle ownership restriction: The choice of an optimal quota policy. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 38(3), pp. 371-402.

Lee, D. H. (2009). Sustainable Transportation Challenge in Singapore. National University of Singapore. Retrieved from

2050.nies.go.jp/sympo/090212/ws/…/2.1_LeeDer-Horng_ppt.pdf

Saad, I. (2011) Vehicle Growth Rate to be Cut. Lowcarbonsg.com. Retrieved on March 20, 2012 from http://www.lowcarbonsg.com/2011/10/07/vehicle-growth-rate-to-be-cut-news/

Santos, G., Li, W. W., & Koh, W. T. H. (2004). Transport Policies in Singapore. Research in Transportation Economics, 9, pp. 209-235. Retrieved from https://weblearn.ox.ac.uk/site/…/Santos%20et%20al%202004.pdf

Tan, L. H. (2001). Rationing Rules and Outcomes: The Experience of Singapore’s Vehicle Quota System. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2001/wp01136.pdf