Comic books and graphic novels: The transformation of reading in the classrooom

Introduction

Ask many librarians or classroom teachers and they will often remark that the comic is a low form of the written word and does not denote “serious” reading on the part of their students. Many will not count reading a comic as part of a home reading program or, at the elementary level, will not allow students to read this type of material during class silent reading periods. Even librarians who willingly add them to their collections often dismiss their importance (Tilley, 2008). In recent years however, the tide seems to be turning in favour of these pulpy little stories. Innovative teachers are beginning to accept the role that comics, and their closely related cousins, the graphic novel, are capable of playing in the education of our children (Viadero, 2009).

Accessibility

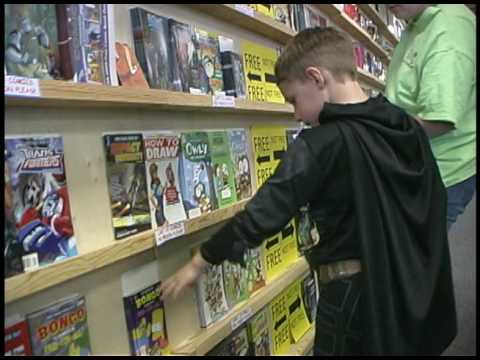

Even though there is evidence of the existence of comics dating back over 150 years they became most readily available during the 1930’s in North American news agents and drugstores (Aleixo & Norris, 2007). This coupled with the low price of the publications made them easily accessible to the public in general and children in particular. In addition there was little competition from other media at that time for, “the time, money, and attention of children” (Jacobs, 2007). Jacobs explains that this ease of availability meant that comics offered a different option for the practice of literacy that was beyond the bounds of a child’s formal education (2007). This increased literacy practice has propelled many children forward as literate members of society and despite the criticisms leveled at the comic world these little books may be better positioned to prepare today’s students for the multiple literacies required in a world where they are constantly inundated by visual images.

Modification and Multimodality

While comics have been much maligned by educators and were even the topic of televised US Senate hearings in 1954 (Kannenburg, 2008), their potential role in literacy education in the classroom is somewhat more positive. It is still rare for teachers to embrace their use in literacy training but it seems that regardless of how scholars define the comic form what seems constant is that in this genre the visual is an important element and, “should not be seen as subservient to the written” (Jacobs, 2007).

It is this combination of text and image that Gunther Kress calls multimodality (Jacobs, 2007). Jacobs maintains that this shift to thinking about comics as multimodal text rather than as a lesser form of writing is significant in the culture of text (2007). It is also significant in terms of understanding the power of comics to teach multiliteracy skills required by today’s students. This valuing of visual literacy has been slow to take hold. Teachers are taught to believe that beginning readers rely on text and that good readers move beyond pictures but the inclusion of comics and graphic novels into the classroom has provided a new generation with an opportunity for layered deconstruction that may help them scrutinize the manner in which interdependent text and imagery creates what has been called, “a strong sequential narrative” (Williams, 2008). This layered deconstruction will involve not only an examination of the text and images but will need to consider the comic author’s use of panels in the creation of the story. These panels guide the reader’s attention and pace the reading in the same way that, “poets use line breaks and punctuation” (Tilley, 2008).

James Bucky Carter (2007) contends that integration of graphic novels into the classrooms of today will transform the study of English. A move away from the notion that literacy is purely text-based will help educators move beyond what he calls, “one size fits all” literacy education (Carter, 2007). This means that the impact of this form of reading may not have had its full impact yet. Its time may still be coming thanks to technological developments that increasingly rely on the user’s ability to process visual images.

Pathways to learning

In many curricular areas the reading of comics affords the educator and the reader a unique opportunity to engage in concepts and ideas that would be, depending on the age of the student, unreachable or difficult in traditional text formats. The inclusion of pictures adds a scaffolding element to learning that can be particularly advantageous in the area of social studies. Williams (2008) argues that, “graphic novels, like a compelling work of art, or a well-crafted piece of writing have the potential to generate a sense of empathy and human connectedness among students”. Visuals combined with text allow comic and graphic artists to ask their readers to consider a different point of view and look at a situation through the eyes of another. In the teaching of social studies this is fundamental to real understanding of both past and current events and represents deep learning on the part of the student.

Conclusion

In these ways, comics and graphic novels will continue to impact and modify our views of text in education. As innovators in the field continue to encourage children to explore this genre the idea that comics are only transitional literature may someday become a thing of the past. Over the past 80 years the progress may have been slow and there have not been any opportunities for comic-like exclamations like “Pow” or “Ka-bam” but new technologies that require a different form of literacy just may be what the comic needs in order to legitimize itself in education.

Resources:

Aleixo, P., & Norris, C. (2007). Comics, Reading and Primary Aged Children. Education & Health, 25(4), 70-73. http://search.ebscohost.com

Burton, D. (1955). COMIC BOOKS: A TEACHER’S ANALYSIS. Elementary School Journal, 56(2), 73-75. http://search.ebscohost.com

Carter, J. (2007). Transforming English with Graphic Novels: Moving toward Our “Optimus Prime.”. English Journal, 97(2), 49-53. http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/EJ/0972-nov07/EJ0972Transforming.pdf

Jacobs, D. (2007). Marveling at The Man Called Nova: Comics as Sponsors of Multimodal Literacy. (pp. 180-205). http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/CCC/0592-dec07/CO0592Marveling.pdf

Kannenberg Jr., G. (2008). The Not-So-Untold Story of the Great Comic-Book Scare. Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(37), B19-B20. http://search.ebscohost.com

Tilley, C. (2008). Reading Comics. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 24(9), 23-26. http://search.ebscohost.com

Viadero, D. (2009). Scholars See Comics as No Laughing Matter. Education Week, 28(21), 1-11. http://search.ebscohost.com

Williams, R. (2008). Image, Text, and Story: Comics and Graphic Novels in the Classroom. Art Education, 61(6), 13-19. http://search.ebscohost.com

Williams, V., & Peterson, D. (2009). Graphic Novels in Libraries Supporting Teacher Education and Librarianship Programs. Library Resources & Technical Services, 53(3), 166-173. http://search.ebscohost.com

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

You must log in to post a comment.