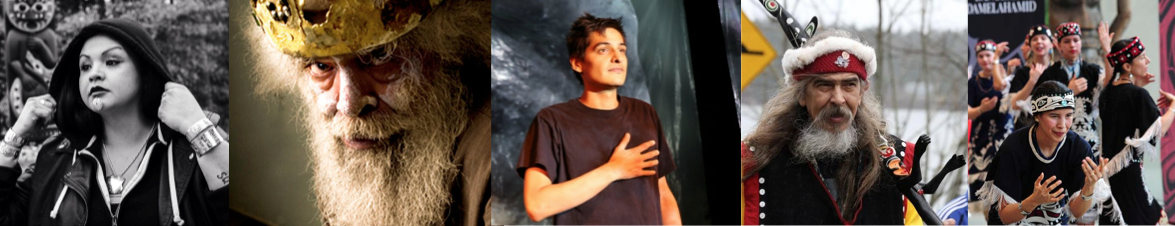

On March 29, 2016 I attended the 2nd Annual Nehiyo-paskwa-itsimowan Pow-wow Celebration at UBC, hosted by the First Nations Studies Student Association (FNSSA). The Nehiyo-paskwa-itsimowan Pow-wow began as a small conversation between Salia Joseph and myself. We both understood the value in pow-wows and recognized a need for an inclusive cultural event on campus. Not thinking too much about it or knowing the amount of work involved, we decided to go forward and begin the planning process. Two years later, FNSSA and the Indigenous Students’ Association hosted the first annual pow-wow in 2015.

The way I was taught, is that pow-wows are a celebration of life through song and dance. It is the intention of the pow-wow to celebrate the resiliency, diversity, and vibrancy or Indigenous people. The name ‘Nehiyo-paskwa-itsimowan’ is cree, “nehiyo” meaning Cree, “paskwa” refers to the plains area east of the Rocky Mountains, and “simowan” means the way she/ he dances. This name recognizes that the pow-wow celebration and the dances originate from the plains people and acknowledges the relationship and responsibilities we have to the Musqueam people and territory by highlighting that it is not a Musqueam celebration or ceremony.

One of the goals of the pow-wow is to revitalize the teachings and practices that were seen at pow-wows between 1950-1970. Many Nehiyaw pow-wow teachings have become dormant. It is not my place or that of the committee to bring back these teachings as we are all still young and learning, rather it is our goal to create a space for teachings to be shared, learned, and practiced. To do so, we invited several Nehiyaw elders to be the head staff, including the whipman, the emcee, the head male dancer and the lead singer of the host drum. Together and in consultation with others, they decided how the pow-wow would be run regarding protocol.

I would like to briefly discuss how protocol was negotiated at the pow-wow and how people responded to certain protocol. It is not for me to discuss in depth the role of the whipman or for me to write about it so it will be a basic overview. The whipman has a complex role within the pow-wow and has a lot of teachings and training that he must go through to have the right to fulfill that role. One of his roles is to invite dancers onto the dance floor and ensure they are dancing when they are supposed. It was shared at the pow-wow that if a dancer refused to respond to this protocol and did not dance when the whipman told them, they would be fined. This is something that I have never witnessed at other pow-wows but have heard stories about happening in the past. At the Nehiyo-paskwa-itsimowan Pow-wow, dancers were only fined $5.00, whereas in the past they would’ve been fined a horse, a tipi, a buffalo robe, etc. This fine demonstrates the seriousness of the role of the whipman, the importance of following protocol, and dancers’ responsibilities and roles within when they make the choice to participate as dancers.

What I witnessed was a range of responses and reactions to this protocol. There were some people who appreciated that the whipman ensured dancers were dancing and said things like “otherwise, I usually just sit there.” Some people appreciated that these teachings were being brought back and being acted upon rather than remaining a memory held by a few of the older ones. Some people were grateful for what was shared and donated $5.00 out of appreciation for what was happening. Even some dancers who were fined took it in a good way and respected and upheld the teaching. However, other people were not so happy with it. A dancer who was fined got upset with the whipman (details of the situation will be left out).

The situation with the dancer being upset brought up questions about the role of witnesses and participants to learn, listen, and respond to protocol. I understand that protocol and practice is something that is always changing and needs to be reflective of who we are today. However, there are many events, ceremonies, and gatherings that have strict protocol. My mother, grandma, and aunties always explained to me that I need to have respect when I attend an event as a witness or a participant. This respect comes first and foremost. Part of this involves respecting the laws that are in place in that space. It is not up to me to decide what parts of an event I take part in or what protocols to follow. When I am invited and choose to participate, I take on the role of respecting what teachings and practices are to be followed in that time and place.

Ultimately, it isn’t about who is right or wrong but rather about how we as guests and participants listen, learn, and respond to protocol when we are invited into a space that is led by teachings and practices that may be unfamiliar.