Brower, A., & Carrol, L. (2007). Spatial and Temporal Aspects of Alcohol-Related Crime in a College Town. Journal of American College Health, 55(5), 267-276.

This paper looked at alcohol-related crime (vandalism, assault and battery, liquor law violations, and noise complaints) in Madison, Wisconsin. Madison has a large university student population known for their high alcohol consumption – rate of binge-drinking of 63% (2007), vs. US national average of 44%. The researchers wanted to look at the spatial and temporal distribution of these crimes to link them to student binge-drinking.

The researchers’ hypothesis was that:

- Alcohol-related crimes will display certain temporal and spatial patterns that prove their connection to student binge-drinking, such as noise complaint calls to the police made from households neighboring high-density student areas at around midnight

Methods

Two Data Sets gathered:

- Student Addresses from students registered in 2003 (from University of Wisconsin)

- Alcohol-related crime calls to the police(from Madison PD and UW PD) in 2003

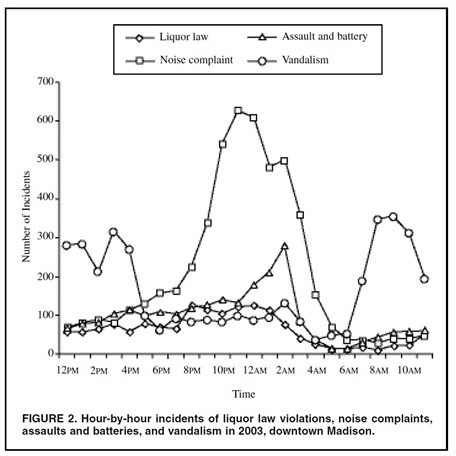

The results were mapped in ArcGIS, with a focus on downtown Madison, producing several maps: areas with high student populations; spatial distribution of crimes; crime locationsat the time when different type of crime peaked (e.g. noise complaints from 11 PM to midnight), as well as a graph showing the temporal (hourly) fluctuation in each crime type.

Temporal crime fluctuations

Results

Several spatial and temporal patterns identified:

noise-complaints calls peaked around 11pm to midnight in areas bordering high student population areas

Assault and Battery reports peaked at 2-3 AM when bars closed down

Vandalism peaked in morning (time when the crime was discovered and reported), and was concentrated around areas with high student populations

Researchers thus found support for their hypothesis.

Limitations

- Incomplete analysis – e.g. did not talk about spatial distribution of assault and battery crimes

- Crimes may have been called in multiple times; others may have not been represented at all because the police responded first

- Poorly-produced maps – poor use of colors and symbols, unclear what exactly some maps showed

- Did not map bar locations

- Made several assumptions, such as that students are the main demographic at bars

- Could have mentioned whether drinking-related crime rates are high or not

Rating: 5/10 – weak paper, but it did lead to policy changes by city and university officials in regards to binge-drinking