We’re still in the Hudson Bay. As we sit in the fog, waiting for unclear plans that have nothing to do with our original research plan (or possibly for Godot, at this point), it would be disingenuous to pretend that the mood on board isn’t frustrated and restless. Several of the Principal Investigators on board – Drs. François, Cullen, and Tortell – have written an editorial in the Globe and Mail about our situation here.

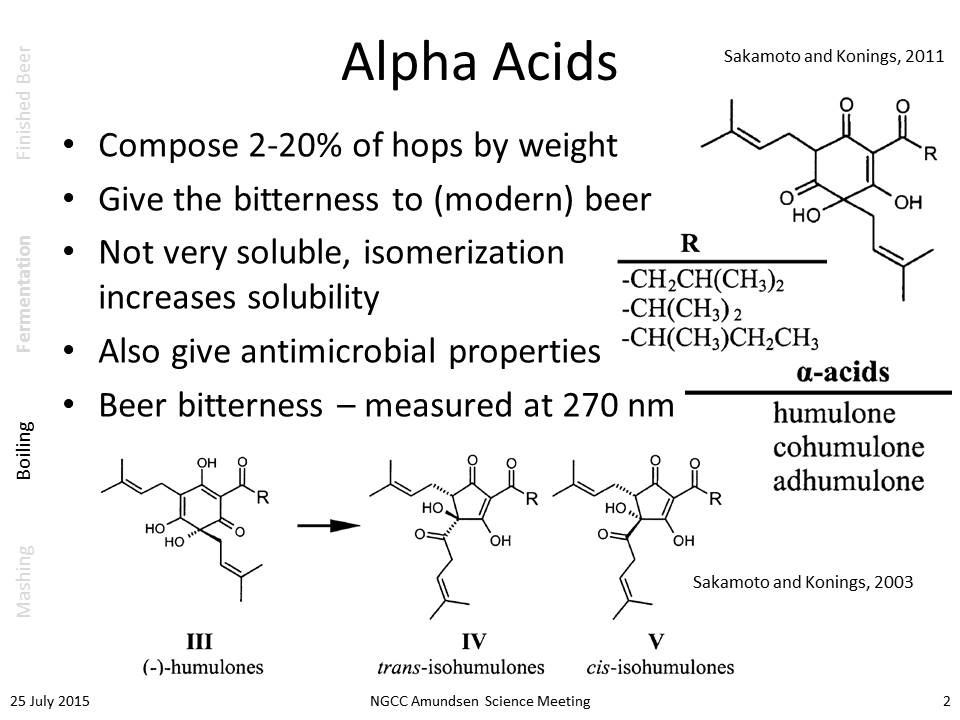

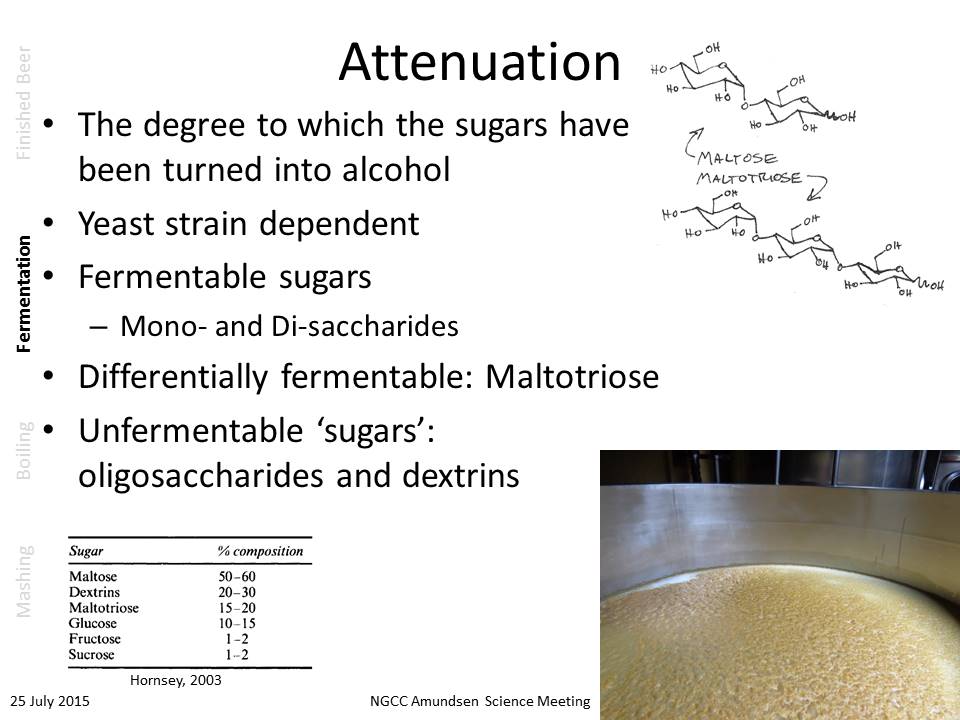

However, we’ve had no trouble finding ways to occupy our time. The ocean acidification experiments are still running. Personally, I’ve spent plenty of hours with my robot, trying to get him calibrated and communicative, which can be tricky as the ship jerks in ice. The nightly science meetings, which were previously completely taken over by very complicated logistics, have begun to include talks given by the researchers on board, which have been diverse in scope and very interesting. Thanks to them, we’ve learned about things like arctic cod speciation, the use of sonar to detect fish stocks, primary productivity patterns in the Labrador Sea, climate-active gasses in the Arctic, and, in one memorable instance, when the speaker was a master brewer, the biogeochemistry of beer.

There is a cribbage tournament, and as of this writing, I’m losing my first match.

Over the past few days, I’ve also been thinking about language dynamic on board. Depending how you look at it, the Amundsen is a ship of either one, two, or upwards of eight languages. The captain and crew, as well as many of the scientists, are francophone, and much of the everyday business on board takes place in French. Because most scientists want to be able to effectively communicate their research to other scientists and to the public (and because English is the main language of communication in the modern international scientific community) the scientists on board are all proficient in English. However, many of the non-francophone scientists are allophone (their primary language is neither English nor French), and many of the English speakers don’t speak French, while many of the crew don’t speak English. Language shapes how we see the world, and so people are coming together on board the Amundsen from very different lenses of experience. It’s remarkable to see people from around the world come to a 70-metre ship and live and work alongside each other, and it’s a privilege to see Canadian, Québecois and international perspectives interacting in our little community in the middle of the Hudson Bay. The spirit of international camaraderie is quite heartening to experience. As an immigrant to Canada, I am keenly aware of how positive – and, sadly, in many places rare – such a dynamic is, and I don’t take it for granted.

Because of the number of languages on board, some of us have spent some time learning various expressions from each others’ languages. This is how we’ve discovered sollbruchstelle – a German word meaning “place where something is bound to break”. For people who work with fragile instruments – most people here have been doing so far longer than I have – it’s a uniquely descriptive one for certain situations.

Meanwhile, the fog gets thicker as we near nighttime.