Here’s my question: where do all of these tourists get off treating everyone so horribly?

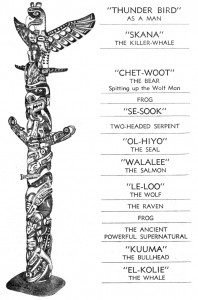

When I read my section I couldn’t help but recognize an overpowering theme of tension. It’s everywhere. There’s tension in the Café, there’s tension between Latisha and George, there’s tension between Eli and Sifton, and there’s tension between the people of the Sundance and the tourists. Tourism for entertainment leads to trespassing, interrogation, curiosity and spectacle of Aboriginal culture. Aboriginal culture is literally explored, put on stage for viewing, and judged like Duncan Campbell Scott watches and criticizes his “Onandaga Madonna”.

It’s not as much surveillance as it is carnival.

We begin with the four tourists at the Dead Dog Café: Jeanette, Nelson, Rosemarie De Flor, and Bruce. According to @eldatari (wordpress):

“The four customers sitting in Latisha’s Dead Dog Cafe are named in reference to Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, who appeared in the 1936 MGM musical, Rose-Marie. In the film, they portrayed the characters Rose-Marie de Flor and Sergeant Bruce; a famous opera singer and an RCMP officer, respectively.”

User @eldatari explains how the Aboriginal character that accompanies Marie de Flor eventually robs and abandons her. This negative portrayal of the only Aboriginal character in the film provides sympathy to Marie’s exploratory, invasive actions. While it is mentioned that Marie’s Aboriginal guide has understandable reason for the robbery, the viewer does not deem his actions understandable.

In Green Grass Running Water, Latisha undergoes awkward, disrespectful interrogation at the hands of Jeanette, one of the other tourists in Marie’s company. Such spiteful inquisition leads me to think that King is alluding to this film to demonstrate the power of trauma. In the case of modern-day Aboriginal culture we continue to battle the echoing horrors of colonialism. By turning the tables and viewing the trauma from the “white” lens, the reader not only recognizes the power of traumatic memory, but also gains sympathy for the interrogated Latisha. In the film we originally sympathize with the white colonial, and in King’s novel we sympathize with the original “evil” Indian.

In addition, this interrogation represents a power-tension between the tourists themselves, as well as with Latisha. Jeanette says that she is “the spokesperson” and “ask[s] all the questions everyone else is too embarrassed to ask” (130) framing an alpha-beta struggle that competes between Jeanette and Latisha. While Latisha is the owner of the café, Jeanette feels entitled to answers for all of her questions. In turn, Jeanette provides playful answers that mock Jeanette’s need for personal and factual information about Latisha and the café.

(Food for thought: Alpha-beta, you say? Sounds dog-like to me.. Dead Dog café, you say? GOD-DOG?)

While there are certainly other interesting parts within my section (mine was kind of a goldmine) I think it’s worthwhile to closely examine the Sundance-photography-incident and how it relates to the ignorant tourists of the café that I just peeled apart.

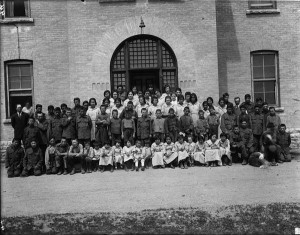

Summary: narrator describes Eli’s yearly trips to the Sundance in his childhood. The narrator explains how “Every year or so, a tourist would wander into the camp…Occasionally there was trouble” (138). One year “when Eli was fourteen… [a] man climbed on top of [his] car and began taking pictures” (139). According to the narrator, photography isn’t allowed in the Sundance.

Here’s that tension again…

Something that resonates with me here that also resonates with me earlier (in Latisha’s section) is the spectacle of Aboriginal culture for white/Western culture. It’s almost like the tourists feel they’re being “respectful” or making themselves “cultured” by visiting the café when it’s really just an invasion, a reason for interrogation, judgemental analysis and pretence. Here, the tourists literally invade Sundance territory to entertain some sort of curious-touristy inclination. The camera shoots pictures, the photo roll given up is black, blank, dead—injury by literacy, death by colonialism. The Aboriginal ritual is rejected in the most literal sense—their legal claim is rejected by the RCMP even though the tourists broke Aboriginal law. Why is one perspective recognized, and another rejected? Even if the café served dog it still obeys the laws of the Blackfoot territory, yet the ex-RCMP officer still threatens “..if we had heard of anyone cooking up dog and selling it in a restaurant, we would have arrested them” (131).

The struggle for dominance has never been so obvious…

————-

Works Cited

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto, Ont.: Harper Perennial, 2007. Print.

Scott, Duncan Campbell. “The Onondaga Madonna Poem.” Poemhunter.com. Poem Hunter, n.d. Web. 11 July 2015.

Tari, Elda. “”Rose-Marie”, or “Indian Love Song” (Part One).” Words and Names. WordPress, 14 Mar. 2009. Web. 11 July 2015.

So I have to admit something. This is my third time studying Green Grass Running Water. When I first encountered the book waaaay back in first year I was unbelievably confused. Thomas King is a complex writer with a lot of meaningful things to say, and I think my first-year English 100 professor aimed her ambitions a little high when she assigned this novel. I remember reading the novel without any background understanding of Thomas King, Western culture and its impact on Aboriginal culture and colonialism. To be honest, cracking this novel felt almost like a joke to me even though it was far from it.

So I have to admit something. This is my third time studying Green Grass Running Water. When I first encountered the book waaaay back in first year I was unbelievably confused. Thomas King is a complex writer with a lot of meaningful things to say, and I think my first-year English 100 professor aimed her ambitions a little high when she assigned this novel. I remember reading the novel without any background understanding of Thomas King, Western culture and its impact on Aboriginal culture and colonialism. To be honest, cracking this novel felt almost like a joke to me even though it was far from it.