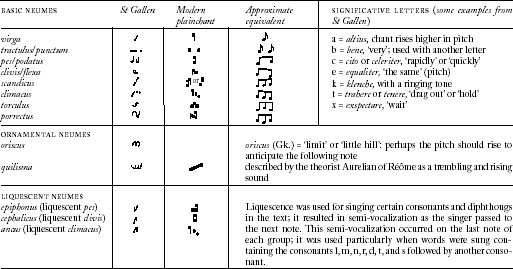

To represent musical sounds on a page is markedly different than writing down language. The musical notation used on these gradual pages take its origins from the neumatic notation system of plainchants and theoretical treatises developed between the 9th and 10th centuries.[1] This early notation depended almost entirely on the singer’s recall of the music being represented.[2] The first basic neumes showed a singer the relative pitches of notes on the page, acting more as a memory aid than a true transcription of the melody.[3] Gradual books and other codices of music were more guide book than instructional manual.

However, developments in transcribing music from the 13th and 14th centuries saw a change in how to represent rhythmic modes on the page through the combining of groups of notes (called ligatures).[4] The introduction of time signatures as mensuration devices for music helped to define the relative rhythmic values of notes. Notations on the page were no longer just representations of pitch but a more comprehensive expression of the expressive sound of the particular melody.

If this particular gradual was indeed transcribed in the 15th century, it would mostly likely be dated early in the century because it does not demonstrate the developments in notation which occurred after 1450. For example, the fact that this gradual is printed on vellum and uses solid black neumes is significant because later in the century, with the popularization of paper as a writing surface, came the use of void notes (notes that were only in outline) because the concentration of ink to fill in the notes would eat quickly through the paper.[6]

It is also important to remember that the developments over time in notation practices were very much influenced by political relationships between the different monastic centres across Europe, the physical geographical distances between cities, as well as ecclesiastical jurisdictions.[7] This particular example of notation is stated as Italian, but would have been influenced by the sacred musical practices of Germany, France, and perhaps even England.

[1] Pryer, Anthony. “notation.” The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed April 21, 2015, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/opr/t114/e4761.

[2] Susan Rankin, “Calligraphy and the Study of Neumatic Notations,” in The Calligraphy of Medieval Music, edited by John Haines (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011): 47-8.

[3] Pryer, “notation.”

[4] Pryer, “notation.”

[5] Pryer, “notation.”

[6] Pryer, “notation.”

[7] Giacomo Baroffio, “Music Writing Styles in Medieval Italy,” in The Calligraphy of Medieval Music, edited by John Haines (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011): 106.