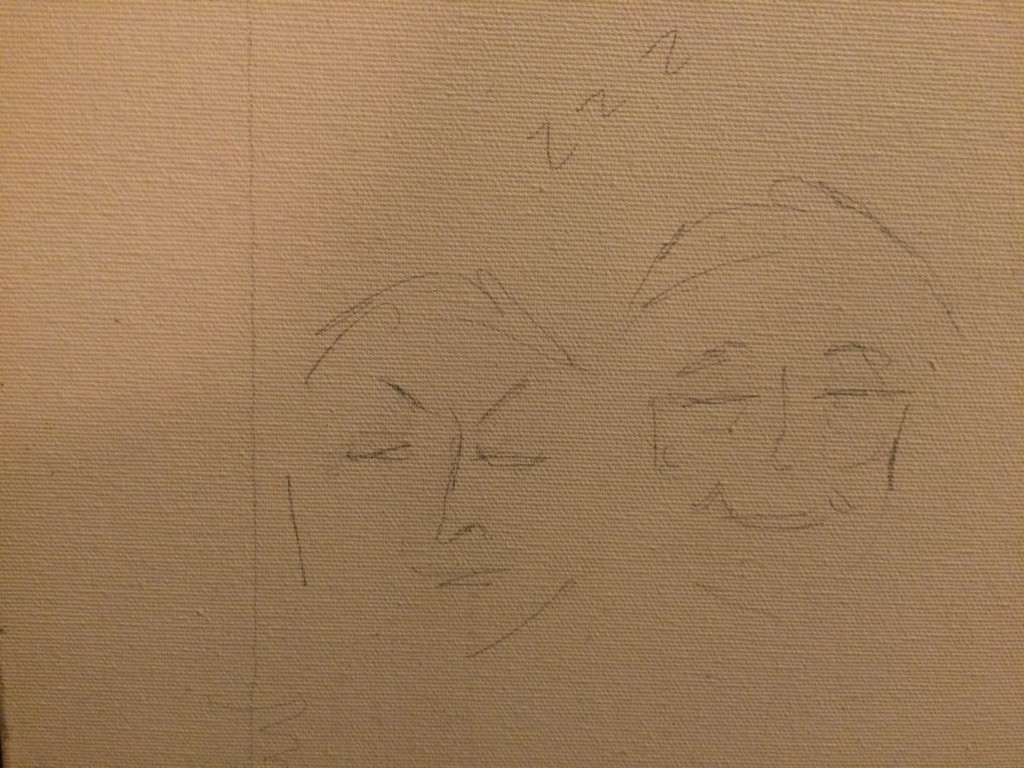

As I start this final entry, I must reflect on the fact that some of these connections are entirely personal and rooted in my own experience/privilege/etc. Then more of it will come from Jane Flick, and the rest from a kind of communal shared knowledge – that of the Western Canadian community I’m from.

“There were color bars on channels two, four, and eleven, static on channel twenty-eight, and a Western on twenty-six” (GGRW 180).

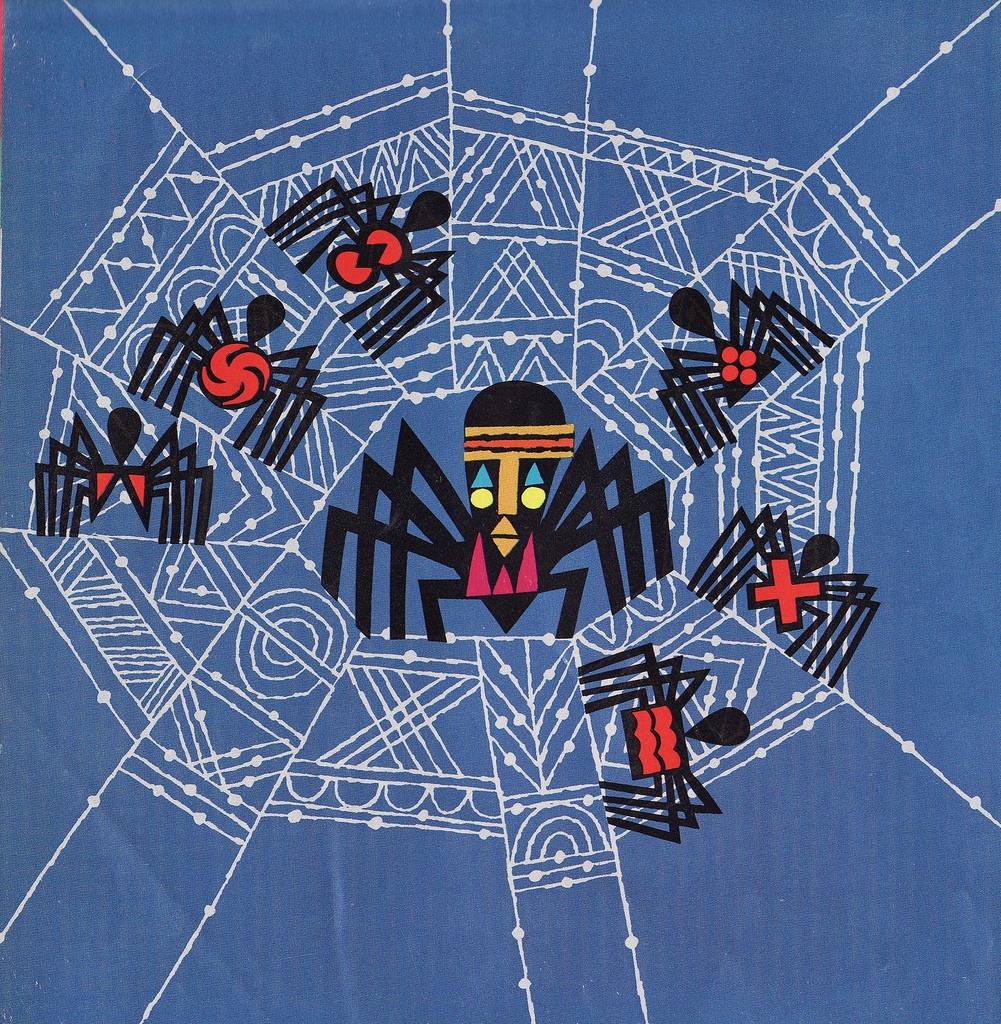

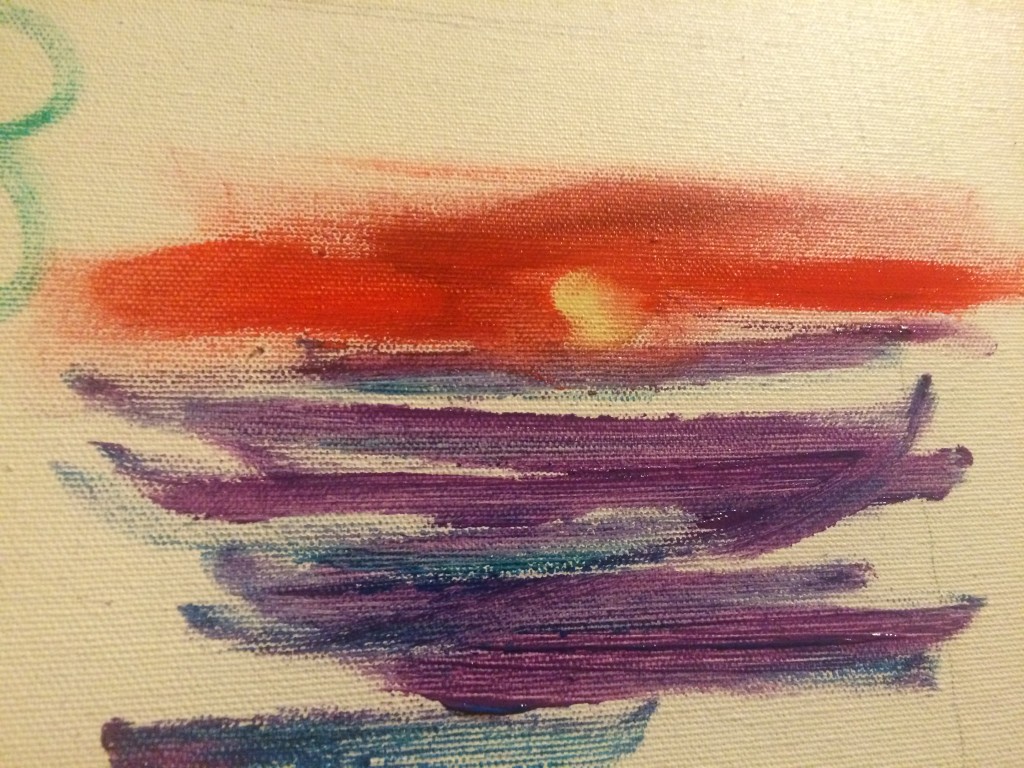

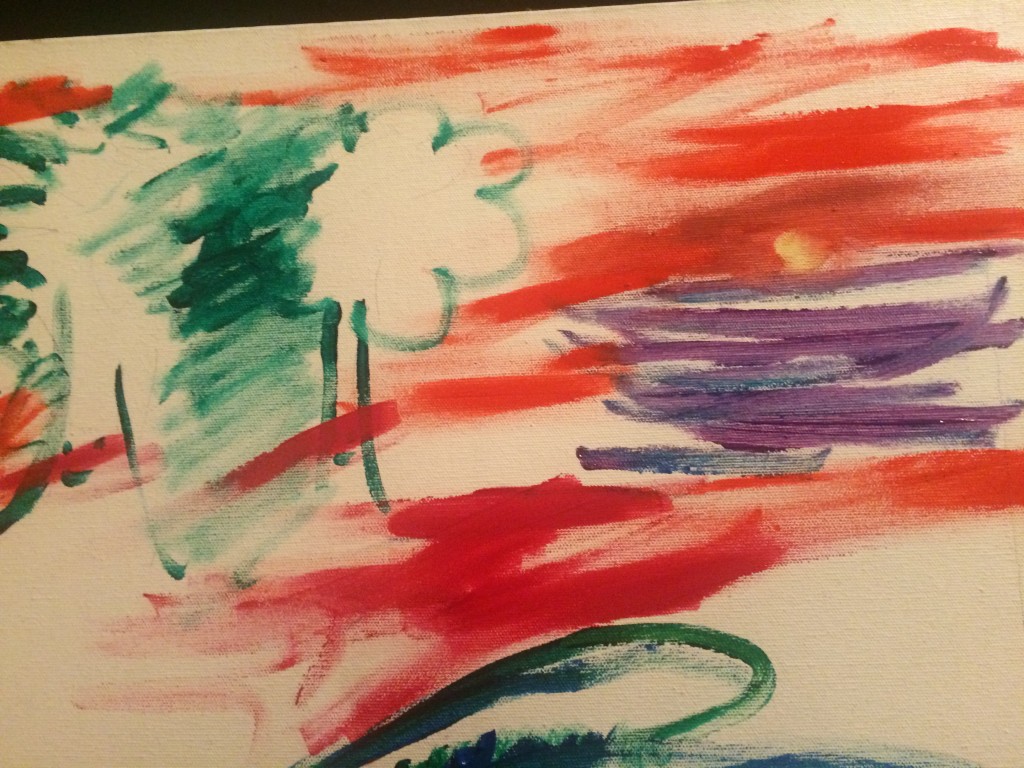

The first things Charlie comes across on the TV are the colour bars. For those who didn’t have this experience, colour bars were hard not to come across. Many television stations did not have late night programming and would display colour bars (and a tone) late at night. There, in the world of the book, King exposes Charlie to colour – separated, delineated, before he taking him into the world of the Western. King gives us first the test pattern, where the colours all co-exist on the same screen, but divided (if formatted correctly – none of the colours should bleed into each other). Then static. A moment of change: a white noise, a blur of sound created. Finally, the Western. There was a chance (and perhaps King is allowing us this knowledge) that in the static the colours could have been blended together. If we look at the colours in the (what feels to me a very 90s sensibility) where they each reflect a different race, then in the black and white static there are two options: one, the lack of colour can subsequently only separate the colours further; two, that the static allows the colours to melt into one another and no longer have clear delineations. Through the Western though, we realize that the former has happened; the Indians will fight they cowboys and they will lose, because if they won “it probably wouldn’t be a Western” (GGRW 193). The Indians will always be separate in the sharply defined world of the cowboys.

Another allusion King makes, is the separation between Charlie’s past and future – simply in the naming of his companions. Portland (his father) is his past, wrapped up in the image of the Hollywood Indian; Alberta is his present (and potentially his future – certainly where he wants his future to go). One named after an American city, the other for a Canadian provence. Both given a separate location geographically, and growing in size. Portland (locationally) is smaller where Alberta is large and expansive. These two people both lay a certain amount of claim to Charlie during different periods of his life, and spatially they reflect it.

On the drive down to Hollywood – Portland amuses Charlie with stories of the people he left behind. Many of these names need to be spoken aloud to hear the phonological link that King is drawing attention to. It wasn’t until going back through Jane Flick’s work that I gained the allusions that King was trying to make. Sally Jo Weyha (GGRW 182) does sound like Sacajawea when said aloud, indeed most of these names (as pointed out by Flick) reflect early discoverers or explorers, most of which were connected to early colonization in the Americas (Flick 157).

When Charlie and Portland arrive in Hollywood, things are not the same as when Portland as successful there before. He is told as much by C.B. Cologne; the C.B. standing for Crystal Ball (GGRW 181). Certainly something that a mystical, fortune-telling named person tells Portland about all of his old pals that have died suggests a more literal interpretation of C.B.’s name. He is not just named after his mom’s favourite perfume (GGRW 181), but literally for a connection to the other side, a knowledge of death.

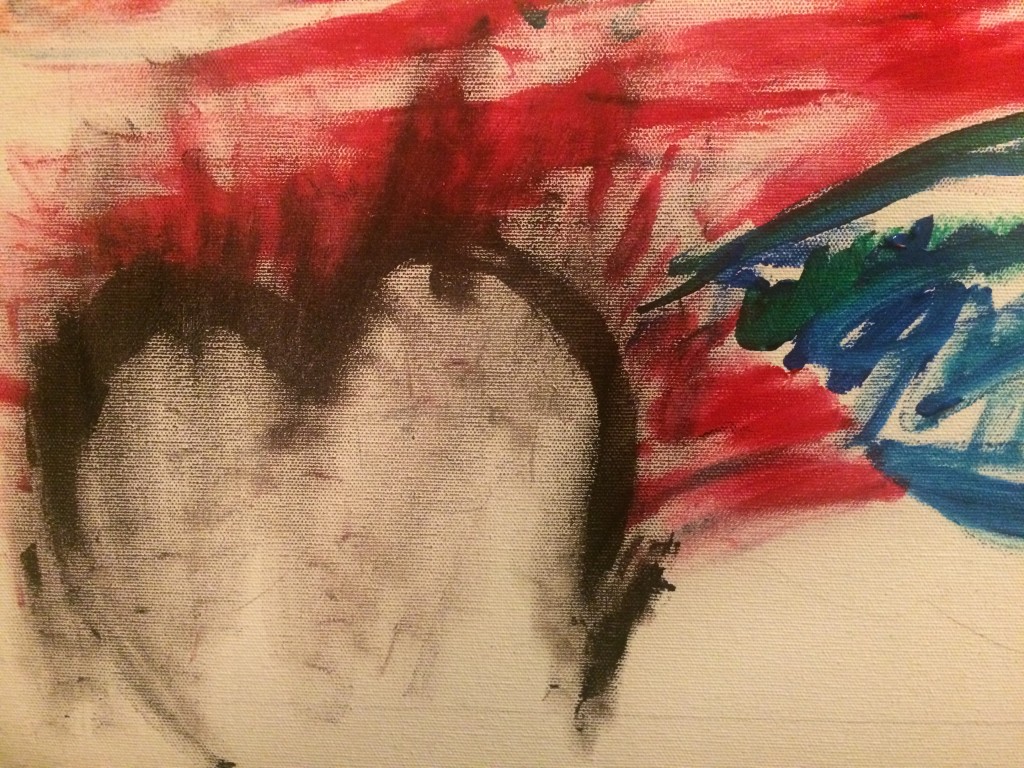

The final connection that I will talk about is about the cars. Charlie is driving his underdog Pinto to go and see Alberta. For those of you that don’t know this – a pinto (in addition to a compact Ford) is also a breed of horse. A rather beautiful one as well.

They are also quite a typically Western looking horse, on the cover (I’m sure) of at least a couple Louis L’amour novels. Pinto’s are distinguished by the blending of colour of their horsehide, they need a certain amount of colour differentiation to distinguish them from a solid coloured horse (that may have sections of another colour – usually along their forehead). King ties the car to something perhaps Charlie is dealing with himself, the blending of a certain amount of white culture vs. that of his ancestry. The co-existence of both colours, both backgrounds, on one man.

Works Cited

“Biography” The Official Louis L’Amour Website. Internet Trading Post LLC, n.d. Web. 10 Aug. 2015. <URL>

Elybaster. “KING TV5 Seattle – Test Pattern 1980s” YouTube. YouTube. 04 March 2011. Web. 9 Aug 2015. <URL>

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161-162 (1999): 140-172. Web. 9 Aug 2015.

Ink it up Trad Tattoos Blog. “Post 108995610661.” tattoome.tumblr.com. Tumblr. Web. Accessed 9 Aug 2105. <URL>

ItsWolfeh. Elsa, Pinto Horse. 2012. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia. Web. 9 Aug 2015. <URL>

King, Thomas. Green Grass, Running Water. Toronto: HarperCollins P, 1993. Print.