Entries Tagged as 'gaming'

Video game obsessions have always mystified me. I grew up in a household where a game console was not welcome and my turn on the computer was closely policed by a thirty-minute timer. I appreciate these rules for what they meant at the time. My siblings and I spent time engaging in many different activities, instead of sitting in front of the tv. When I did spend time with friends or cousins who lost themselves in a video game world I sat on the sidelines, quietly observing, not needing to participate actively.

There are many issues surrounding video game use. The violence issue is prevalent, though somewhat challenging, considering violence pervades every aspect of life, from sport to real-life news. Another is physical health, as the most enduring video games require players to be sedentary. These, and more, issues aside, denying that video games have their benefits is difficult.

Gee (2005) outlines the learning principles that “good” video games employ. Reading these makes complete sense to me. Video games engage students on so many levels. As an English teacher, I want my students to be actively using their minds as much as possible. Granted, I often encourage regular reading and writing and not video gaming, but if these games are getting them to think critically, problem solve, make connections and identify with a narrative – what is the difference? I am certainly not saying that students should be playing games instead of reading or writing. Ideally, there should be a mix of all three…but that isn’t always possible for all kids. I think what I’m beginning to see and promote is the value that can be present in video games. So many students love to play them, and a great deal of adults are quick to denounce their worth. If students are passionate about something, how does it make them feel when their passion is depicted as a waste of time?

As educators, we place value in many different types of narratives, why not video games? What students are interested in is important. In the ELA classroom, we have so much opportunity to give our students choice – why not let them try to design a level of a video game, or make a comparison between a game and a poem? The end product could be extremely rich and rewarding for both student and teacher.

Tags: gaming

I found an article on commonalities between digital games and literacy by Apperley and Walsh, which articulates the significant educational value, particularly in the area of literacy for classroom activities. Direct quoting from Apperley and Walsh’s article, “By including the reading, writing and design of digital game paratexts (gaming language) in the literacy curriculum, teachers can actively and legitimately include digital games in their literacy instruction.” It assists teachers in identifying the elements of game play that would be appropriate for the demands of the literacy curriculum.

I have been discussing with colleagues about implementing gaming into classroom, and apparently, some people dislike the idea of taking away the fun part from what the students like to do and forcibly turning it into something educational. However, I understand the whole implementation of gaming as using the pre-existing gaming literacy skills into literacy teaching and curriculum rather than using it as a motivator as if we are trying to persuade students to feel the same kind of “fun” while learning. Young people already play by a certain set of “rules” in their gaming spaces, using characteristic tools and language, and holding certain values. There must be a value in gaming and teachers are trying to take away the goodness in it like what Apperley and Walsh are trying to argue: “[gaming literacy] provides an authentic segue between [the students’] immersion in gaming culture and gameplay practices and school-based literacy outcomes.” There is a strong correlation between the two, and I believe that it is the educators’ responsibility to make every means applicable to learning.

Then it comes down to the issue of “content.” I agree with Gee on the point that we certainly do “learn, use, and retain lots and lots of facts” (content), and these “facts come from and with the doing.” We discussed the value of bringing gaming into English language art classrooms during the seminar. I personally love playing video games, RPG (role-playing games), smartphone games, and all kinds of games in general. (I used to play video games until I realized that it was morning…) With that being said, I strongly agree with the idea that games incorporate learning principles. I personally think that I have been significantly influenced by

Also, to support the quality and validity of literature in games, I want to draw attention to novelization of some games. There are great examples not only in North America, but the market is much larger in Asia. Video games transform into novels, movies, and comic books with considerable popularity. We do not even need to force our students to write a game script to make the topic applicable to English Language Art classes; just by discussing and treating it as a genre of literature and literacy, I think gaming has a space for education and learning in English classrooms.

Apperley, T., & Walsh, C. (2012). What digital games and literacy have in common: A heuristic for understanding pupils’ gaming literacy. Literacy, 46(3), 115-122.

Gee, J. (2005). Good Video Games and Good Learning. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 85(2), 33-37.

Tags: gaming

“How do you get someone to learn something hard, long, complex, yet enjoy it?”

This is a great core question raised by Gee in the article; after all, it is one of the many struggles that teachers face in the classrooms.

To be honest, how many students would choose to take English classes if they had the choice? In my younger days, I would have avoided the subject like the plague if it were not for my grade twelve English teacher. To reflect on the question, the root of learning is to actively enjoy gaining knowledge and skills as it is human nature to enjoy learning. But oftentimes, schooling makes it not. Referring to the article, I am not implying video games are the only the solution to boring classrooms; I believe that it is not harmful to utilize gaming to cater to students’ interests and engage them in English classes

As well, the article does not advocate playing video games in class; rather the focus is on educating through the principles of gaming. For example, all too often students are learning content to pass tests; they have not acquired the knowledge and often have difficulties in applying the knowledge to other problems without practice. However, in video gaming, people often learn various skills through incessant practices (that are fun, usually) and apply it in different contexts and situations. Then, is it not time to deviate away from the conventions of traditional schooling (a bit) and reconsider what teachers can do to make learning “doing”?

(more…)

Tags: gaming

“You will write if you will write without thinking of the result in terms of a result, but think of the writing in terms of discovery, which is to say that creation must take place between the pen and the paper, not before in a thought or afterwards in a recasting…It will come if it is there and if you will let it come.” Gertrude Stein

My second multimedia project for this course focuses on the process of poetic composition. I used Quicktime to screen capture my creative process as I wrote. When I showed this performance to my class they suggested that the poem might do well to be scored. I instantly thought of Mozetich’s “Postcards From the Sky” (look it up). So, as for my piece–watch it and consider having your ELA classroom experiment with their own performance poems. Don’t worry about a “rubric”. This is a process, remember? It’s all about feedback. Have a conversation about it. Have 3.

My performance can be seen here.

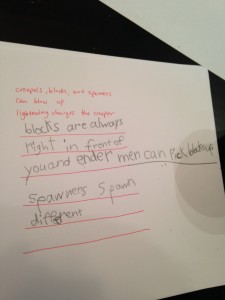

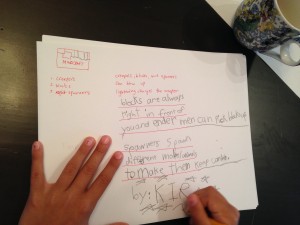

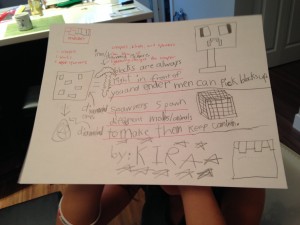

Incidentally, here is the process of an 8 year old in action writing about Minecraft and then drawing a picture inspired by her poem:

Tags: gaming · Media Project II · multiliteracies · Visual Literacy

After yesterday’s discussion on gaming and how to incorporate games into the English classroom I was curious as to how exactly I could do this. I’ve often played video games for long periods throughout my life. I would get hooked on one game and would play it consistently until I beat it once, then I would replay it using cheat codes. Since I have some knowledge of gaming I have been thinking about how I could use that knowledge in the classroom. I do not agree that there is no place for gaming in the English classroom. I think that many of the problem solving techniques and self-correction that we develop help us guide our train of thought when reading difficult text and analyzing. I wouldn’t say that all video games can enhance student’s skills. It really depends on the activities and purpose of the game.

There was a game mentioned in class called ‘One and One Story.’ I looked it up and started playing it. This game requires you to move the two characters around so that they eventually meet face to face. There are obstacles that are placed in the game that you have to maneuver around. The levels also get increasingly harder as you progress.

As soon as I started playing the game I immediately could see that it would be beneficial for a student to play this game. Students have to rely on their problem solving skills to advance in the game. There are no hints available to the players and there are an unlimited amount of tries or lives available. I think that is the most important element to the game. Not everyone gets things right on the first try or even within three tries. I think the message behind the unlimited amount of lives available is very positive and encourages students to keep trying when they are problem solving because eventually they will get it. As you progress in the game the rules of each level change and so do the mechanisms. Things that you tried in the past levels do not necessarily work so you must change your approach. Which again provides students with a message; that you cannot approach each problem the same way. Finally, the game has an underlying story. It isn’t very detailed and is summed up before each level with a short sentence. However, the summary of the story must be interpreted because it provides players with a clue as to what it is you need to do in the next level. In lieu of direct instructions on how to play each level it is hinted at through the text provided. I thought that this was a brilliant way to engage players in the story and also give them instructions.

I loved this game but I personally do not know if I would want to use it in the classroom. The storyline was great and I think there are a few activities that could be done with it but I’m not sure it’s a direction I would like to take.

Tags: gaming

Robb Ross: Commentary on presentation on “Good Video Games and Good Learning” article by James Paul Gee

I enjoyed this group’s presentation and thought they explored the topic of how engaging with video games develops universal and transferable skills. However I would like to further expand on the conversation that ensued after.

But before I do, Teresa, could we just consider the emails we exchanged on this subject to be my 300-word commentary, and call it a day?

lol

About 2 hours ago, as we were walking, I suggested that perhaps there was a link between the fact Naz, Peter, and I spoke critically of this topic because we have Master’s Degree and are older than other students. Therefore, we may have more entrenched (conservative) views about writing and the study of English. I have to confess that I harbor a very judgmental view that anyone reading comics or watching anime after the age of 12 is in some form of arrested development. Cognitively I know that’s harsh and limiting, but it’s just a visceral reaction I have. So when I hear about using games in the classroom I shudder.

Another issue is that for the past 4 years I’ve been an overseas high school IB teacher. I don’t teach ELA. My students write papers on existentialism in Albert Camus’ The Stranger or explore alienation in Kafka’s Metamorphosis. As well, the syllabus is packed and I often have only 12 classes to teach a complex novel and also conduct assessment. Therefore, time is an issue.

Part of the problem is that I’ve been pondering the use of video games in English lessons for only 4 days. I’m going to need time to evolve on the issue. As I said in class, I would think that the validity of using them could be tied to the nature of the text. Fantasy novels like The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe like C.S. Lewis would seem to more naturally mesh with learning through video games.

Probably the comment that most resonates in my mind is when you said that the types of narratives that exist in video games also exist in literature. Both can be equally complex or simple. As that’s the case, then video games can be a valid way to motivate students and explore the text.

What it likely comes down to is that I stopped playing video games when I was 10 years old. I just don’t know enough about them yet to make an informed judgment.

Tags: gaming · Uncategorized

While I understand that it is the process and principals of video games that Jim Gee is interested in, I would like to speak for a moment about their content, and the possible applications of it. I spoke briefly in class about video game narratives, as a genre, and I would like to expand on that idea here.

When I was young and had the urge to write a story, I only ever wrote in one form: video game narrative. I would spend weeks or even months on one idea: drawing maps and pictures of the world, writing notes about the environment, discovering characters and creating histories. My notes were extremely detailed, because the assumption was that the player would be able to interact with all aspects of the world, and I had to devise exactly how the world would respond to this interaction. In addition to this type of writing, I would also create a somewhat linear narrative that would serve as the central narrative for the game. This narrative kind of resembled a tree, as it would have changing parts, depending on player action.

While the process of writing this narrative may or may not have resembled that of someone in the beginning stages of devising a novel, I HAD to consider it as the start of a game, specifically. I had to imagine the story as one that would be experienced specifically by playing through it. The way one experiences a narrative in the form of a video game seems to be specific to the genre; you have to work for the story. You cannot learn what happens next until you earn that information; you are very actively engaged in discovering the narrative.

Additionally, because video games are primarily a visual genre, there are aspects of the writing that would be similar to that of writing for the stage or the screen. The aesthetic of the game, visually, contributes significantly to how the game is read. I spent a lot of time imagining and trying to put down in words the intended atmosphere of the game: the way it looks, the way it sounds, how players move through space, how items react to being touched. All of the these components contribute to how the player reads the game and experiences the narrative, just as how angels, lighting and music affect the viewing of a film. I would have notebooks full of notes and pieces of prose dedicated to games I was writing, focused on these details.

I bring this up to suggest that my experience of pleasure writing video games cannot be more sophisticated or intensive than the process of writing a video game that is actually made. What I am trying to say is that this thoughtful engineering lies behind all games with rich narratives. As such, they are just as valid as film, literature, or theatre for study and critique.

Tags: gaming

The notion of “fun and games” often alludes to children playing games and having fun in their spare time outside of the classroom environment. If children and adolescents have fun outside the classroom, shouldn’t they be able to have fun inside the classroom too? In James Gee’s article, Good Video Games and Good Learning, he articulates the value in playing games in a classroom setting in order to develop a particular skill set involving problem solving, risk-taking, and exploration. Gee states that students “cannot apply their knowledge to solve problems or understand the conceptual lay of the land in the area that they are [currently] learning” (Gee 34). Rather, students are often taught to develop memorization skills and in turn, their ability to regurgitate facts. Although memorization may be a valuable skill, it does not prepare students for entering a world that requires the ability to problem solve and think critically on a daily basis. Students should be taught skills that are transferable to real life situations. The incorporation of games of all forms in the classroom environment will allow students to take risks and have fun in the class and will thereby motivate students to become more engaged in classroom activities.

Prior to reading Gee’s article, I can’t say that I had thought much about incorporating gaming into my own classroom environment. Yet, I think that many of the skills that you can learn from gaming are incredibly valuable and would be beneficial for an individual as they move forward in their life. For instance, one key skill learned when gaming is risk-taking which I think is a skill that many people overlook. Gee states that gaming encourages students to “take risks, explore, and try new things” (Gee 35). Gaming can allow students to create narratives based on the stories they create within the gaming world. Gaming also gives students the opportunity to fail and try again. I can’t stress the importance of this enough. Gee argues that in the gaming world “failure is a good thing” (Gee 35). In many online games, an individual may lose a level and then be given the opportunity to restart that level shortly after. In this type of environment, students get the chance to make mistakes, learn from them, and then apply their new skills when they try the level over again. With age, students will learn that much of life is about trial and error. Learning how to take the knowledge learned from one’s mistakes and how to use that knowledge to find success in future endeavors is a life skill that is applicable to any person’s life.

Classrooms around the world are often filled with bored and unengaged students. Games have the ability to engage students for hours on end and encourage students to consciously think about the decisions and choices they are making online. The modern classroom should engage students and make them excited to come to class. Gee writes in his article that “Humans actually enjoy learning, though sometimes in school you would not know it” (Gee 34). I think that using gaming in the classroom has the potential to give students agency and will give students a sense of control and ownership ownership over what they are doing (Gee 36). I don’t believe that games should make up the entire curriculum for any particular course. However, I believe that if educators use games in the classroom environment in conjunction with traditional methods of teaching, student will become more engaged and more likely to remember the material they are taught.

References

Gee, J. (2005). Good Video Games and Good Learning. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 85(2), 33-37.

Tags: gaming · Weblog Activities

Hamlet Game

Hamlet rubric

Although I didn’t get a chance to teach Shakespeare during my practicum, I can appreciate how difficult it must be to make it interesting for students who several hundreds of years removed from the original context in which the plays were written an performed. I know that I personally didn’t show a real interest in Shakespeare until I studied it during my undergrad at the University of Victoria (thanks to a very good professor).

When approaching Shakespeare’s tragedies, I always start with one question: Is this a “tragedy of bad luck” or a “tragedy of bad choices”? While I don’t want to necessarily limit Shakespeare’s writing to those two schema, I find that they are a good place to start to get the conversation rolling. As soon as you can start pin-pointing what lead to the fall of the protagonist in these plays, they become much easier to read (especially once you start recognizing patterns).

That being said, I read Hamlet as a “tragedy of bad choices.” Not only does he make bad choices, but the choices occur simultaneously (he is damned if he does and he is damned if he doesn’t); that means that it is also a tragedy of “bad luck” because he is only left with two really bad choices that will get him into trouble, no matter what choice he makes. My approach to this project, therefore, is the possible beginnings of a project that students could do to explore what would have to happen in the play in order to give Hamlet a happy ending (if a happy ending is possible).

Since this is very much a game of “what if,” I felt that a roleplaying game or a “choose-your-own-adventure narrative” would be the best medium for this assignment, since these are both genres with an emphasis on choice and what happens when those choices are made. I tried out some free software for making simple roleplaying games, but these proved to be way too challenging for me and I could only imagine how difficult it would be for my students to have to figure out how these platforms worked. I wasn’t sure how much band-for-their-buck they would get from that approach so I decided to do something simpler. I found that using hypertext in powerpoint proved to be quite useful. It may not produce the fanciest game, but it is a good project to introduce the students to the process of using hyptertext and making powerpoints (which are media literacy skills that they can use) as well as give them an interesting and meaningful way to engage with the text.

Since I was only using the most basic bread and butter of the plot of Hamlet to inform my prototype, storyboarding wasn’t a huge issue. My focus was on where the pivotal choices were made, why they were made, how they might be made differently (and what would have to take place in order for that to take place), and what would happen afterward. For that purpose, I broke my “storylines” into the following scenarios (SPOILER ALERT!!)

Bad Choice #1: Hamlet stabbed Claudius.

Throughout the play, Hamlet is provided with clues and evidence that indicate that killing Claudius (in spite of what he did) was not the best course of action. He was being ordered around a ghost who was described as appearing to be sinister in nature and action (also, as a side note, good kings don’t usually get assassinated, sent to Hell, and come back as ghosts). But the pivotal moment in the play is when he sees Claudius praying to God for forgiveness for what he has done; when presented with the chance to be merciful, he chooses vengeance instead. Because he has made this choice, his death is inevitable for two reasons: he is motivated by revenge (which is a privilege that belongs to God) and he is killing a king (even though he isn’t exactly a righteous one). Assuming Shakespeare didn’t want to be put out of business for writing plays where people got off scott-free for killing kings, Hamlet had to die.

There are two ways I was thinking of playing around with this question. The first is what would happen if Hamlet didn’t kill Claudius. These scenarios either had to involve Hamlet avoiding the conversation with the ghost altogether, having a change of heart in the chapel scene, or deciding right away that ghosts are scary and that it is best not to listen to them (making Hamlet a coward, but a living coward). For the purposes of this project, I only focused on the choices that Hamlet made at the beginning of the play; in this case, he either makes nice with Claudius and Gertrude right away or he runs away from the ghost (because ghosts are scary, evil, and don’t offer good advice). At the ends of these storylines, Hamlet and Ophelia live happily ever after. If we learned about the assassination, King Claudius dies of an un-suspicious heart attack.

Bad Choice #2: Hamlet doesn’t kill Claudius fast enough.

The problem with the “Hamlet kill Claudius” scenario is that we know that Claudius murdered King Hamlet. As I mentioned before, you are not allowed to have murdered kings go unanswered for so it has to be resolved somehow; Hamlet has to be the one to do it because he is the “man of the family” and therefor needs to be the one to avenge his father’s death and kill his father’s murderer. In this situation, Hamlet makes the mistake of waiting too long to kill Claudius. Arguably, he could have killed him in the chapel and the stage would have been a whole lot less bloody at the end of the play.

For the options that I provided for Hamlet to be sneaky and careful about how he went about to kill Claudius, the story pretty much went in the same direction as the play usually goes, which is that Hamlet goes crazy and kills and/or terrorizes the household before the final scene, where we find Fortinbras surrounded by dead bodies on the stage.

Again, since I was focusing on choices Hamlet could have made at the beginning of the play, I just decided to have Hamlet push Claudius down a flight of stairs. Again, the problem here is that Hamlet has just killed a king (which is bad) so Hamlet had to get caught and executed for his crimes (as noble as they were).

As with my first media project, I would probably leave assessment pretty open and flexible when it comes to the scenes and alternate endings that the students come up with. My main criteria for this is that the artistic choices are clearly informed by the text and the social, moral, and religious conventions of Shakespeare’s day were adhered to (even if the characters are somewhat modern-looking, as was the case with mine). Since this is also a “powerpoint project,” I would also be assessing the quality of their powerpoint (if all the hyperlinks work, if the font is readable, etc.).

Also like my last project, a good chunk of the mark would come from an artist’s statement that would accompany this project. This is where I can really tell where the students’ thoughts are and how well their ideas are grounded in the text and period of the work which is what I’m assessing in the first half of the assignment (which also makes it useful for a cheat sheet).

I think that the main challenge for this project is that it runs the risk of becoming huge and too big to be completed because there are so many directions where it could go and it is easy to want to do everything. To avoid this problem, I would maybe limit the students to exploring one of the problems that I presented earlier and one or two alternate endings. The students will also need very specific instructions on how much of they play they should quote directly from the text and how much they should summarize. I think this could be addressed by giving them a “slide count” for their powerpoints to give them some boundaries.

Tags: gaming · Media Project II

“What you learn when you learn to play a video game is just how to play the game”. James Paul Gee outlines this as a dismissive statement from people who devalue the learning benefits of playing video games in his article “Good Video Games and Good Learning”. He explains that students should be “learning how to play the game” within their classes in school (Gee, 2005, p.34). As part of my teaching philosophy I aim to guide students in learning how to be self-aware of their own learning styles and how they best acquire and negotiate knowledge. Education is much more than learning the content. I believe that students will be much more successful when they can identify how they learn, instead of solely what they have learned. I strongly agree with Gee’s article as he argues that there are many valuable aspects of “video games [and how they] incorporate good learning principles” and that educators should investigate this idea to engage and motivate students in the classroom (p. 34). I am a strong proponent for promoting and facilitating fun and learning conjointly in school. I strongly agree with the learning principles that he puts forth in his article. If teachers can incorporate some of the learning principles Gee identifies, then they can assist students in navigating their educational endeavours.

Reflecting on my practicum, I had the opportunity to teach Social Studies 8, and it was definitely out of my comfort zone since I have only been prepped to teach English. I had to stop myself from worrying and instead ask myself “How can I make this fun, for both, my students and I?”. During a unit on Feudalism and the Middle Ages, I challenged myself and the students by creating a final project where they got into groups and had to write a script for a mini-play depicting a conflict that could occur within the hierarchy during the time period and then perform it for the classmates. At the end of the unit, I asked students to fill out an anonymous feedback slip and students communicated that it was one of the more exciting projects they have completed. I received comments that expressed how they enjoyed the flexibility and creativity that the project allowed and their positive regard in being to able to verbally and kinesthetically communicate the content they learned. As I read Gee’s article, I made many connections with this experience. To name a few of them, many of the students enjoyed this project the same way some people enjoy video games. Before they started the script writing process, I asked each student to be responsible for creating a character for themselves by completing a character bio worksheet, which matches with Gee’s learning principle 1. “Identity”. Students became committed to their self-designated characters within their project (p. 34). It also offered “challenge and consolidation” since it allowed students to create their own problem or conflict and write a solution to resolve it, while applying and synthesizing the content, which creates “a mastery” of key concepts from the unit. As well, this project connects with principle 2 and 3, “interaction” and “production” (p.34,35). Students were able to work together to make decisions and offer feedback in the script writing process.

Overall, the question Gee poses about how video game creators and educators ask a similar question of “How do you get someone to learn something long, hard and complex, and yet still enjoy it?” is definitely worth taking time to consider (p.34). I think it would be great if we could harness the enticement and motivation video games create and bring that same attitude into the classroom. It would definitely change the classroom environment into a much more engaged place where students will be more invested in learning.

Gee, J. (2005). Good Video Games and Good Learning. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 85(2), 33-37.

Angela Lee

Tags: gaming