Displaying frequently-used characters is fairly straightforward, but what about the less commonly-used ones? One helpful resource, especially for users of Mac OS, is the Chinese Mac web site (see particularly the sections on character sets, fonts, and input methods). Here are some of the more useful tools I have found:*

Fonts

To properly display Chinese characters, a system must have the necessary fonts installed (use this test page to check your current setup). Here are some of the more inclusive ones:

- HanaMinA.ttf (CJK Unified Ideographs, Extension A, Compatibility Ideographs, Radicals, Strokes, HKSCS [香港増補字符集], etc.)

- HanaMinB.ttf (Extensions B, C, D, and E)

Simsun (Founder Extended) 宋体-方正超大字符集

- sursong.ttf (over 64,000 characters, including most of the CJK Unified Ideographs Extension B block)

- “contains the CJK Unified Ideographs block, Extension A, and a selection of 6,217 characters from Extension B; duplicates the coverage of GB 18030, HKSCS–2001, Japanese JIS X 0213, and Vietnamese Hán-Nôm Extension B characters already present in other fonts.”

- Mojikyo M101–M203 (“over 50,000 characters in the Morohashi dictionary [大漢和辞典] and its supplement, along with additional characters, including coverage beyond Unicode”)

- download page

e-Si ku quan shu 四庫全書 (log-in required)

- FZKai-Z03 (a special character set developed to display the large number of unusual characters found in the electronic Si ku quan shu)

- a special character set developed to display the unusual characters used in the Scripta Sinica database

CHANT 漢達文庫 (log-in required)

- a special character set developed to display the unusual characters used in the CHANT database

Looking up Characters

Now that you have the necessary fonts installed, you would need to look up the individual characters to display them. For frequently-used characters, you may consult the section on input methods in Chinese Mac. For less commonly-used characters, you may search in:

- (Mac OS) “Character Viewer” (search by radical)

- Unihan (search by radical-stroke)

- CHISE IDS (search by components—e.g., typing 弓長 would yield 張、漲、、etc.)

Looking up Variants

If you can’t find a particular character, it may be because it is a variant of a more standard character. Here are two useful tools:

- Dictionary of Chinese Character Variants (search by radical-stroke)

- (Mac OS) Unihan Variant Dictionary (look up possible variants of a standard character; limited scope)

Inputting Characters

Instead of the standard input methods (including Cantonese), you may sometimes find it necessary to input a character by its unicode:

- (Mac OS) switch to “Unicode Hex Input,” hold down the option key, then enter the hexadecimal unicode value (e.g., 5f35=張)

- to enter a character in HTML, enclose the hexadecimal unicode value in “&#x … ;” (e.g.,

張=張)

Creating Fonts

If you need to create your own fonts, here’s a recommendation by others: Fontforge

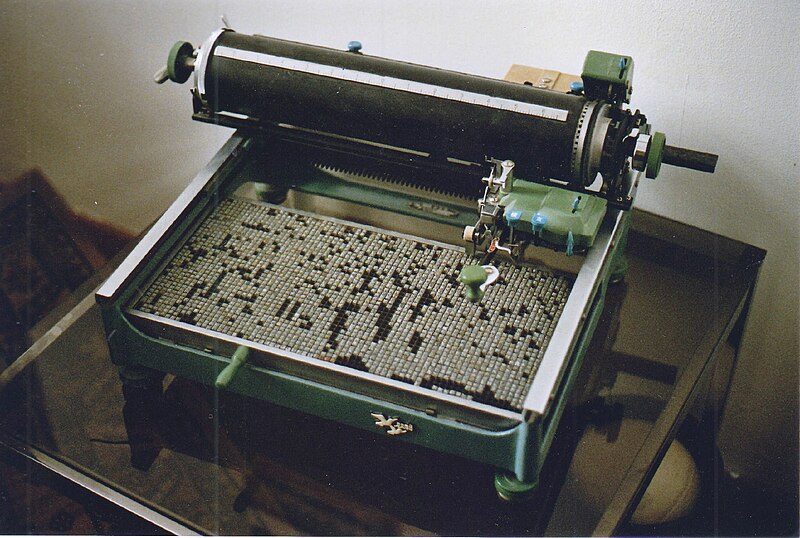

* With thanks to Matt Anderson, Sarah Basham, and—of course—Eric Rasmussen and other contributors to Chinese Mac. Image credit: wikimedia