By Johann Fuhrmann and Max Duckstein

As we get closer to election day, the topic of vote-buying is increasingly coming up in daily conversations in Mongolia. Despite anecdotal evidence of vote-buying being widespread, statistically informed knowledge about the extent of the problem is often lacking. But to understand the dimensions of the phenomenon requires an analytical differentiation: bribes or gifts by political parties or candidates do not necessarily imply a significant influence on the voters’ decision-making process. While the impact of accepted bribes is hard to exactly quantify, surveys offer the possibility to learn more about their effects.

Especially when so-called “ballot selfies” or pre-filled ballot papers are not used, the pay-off of the voting incentives is hard to estimate, even for the briber. Asking people directly if they received gifts or monetary incentives from political parties or candidates in the past and how this influenced them in their decision-making is a limited but worthy option for exploring these cases. A study was commissioned last year by the Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation to survey this interaction. 1,400 randomly-sampled inhabitants of Bayanzurkh, Bayangol, Chingeltei, and Nalaikh districts in Ulaanbaatar and 600 randomly-sampled people from Uvs and Dundgobi Aimag were interviewed.

Much ado about (almost) nothing?

One of the most surprising results of the study is that only 3.3 percent of the rural and only 8 percent of the interviewees from UB stated that they received any form of gifts during the 2016 parliamentary elections! This includes cash, food, or any other form of gifts. While cash makes up for by far the most of the received donations, other handouts include pastries, rice, and everyday items like kettles or clocks. Cash handouts were usually between 10,000 and 50,000 MNT and were sometimes combined with other forms of presents. The apparent relative insignificance of the phenomenon matches common anecdotal evidence which usually places the target group of these (non-)monetary transfers inside specific disadvantaged socio-economic groups. Or, to put it differently, hoping to influence someone’s intended vote by gifting them 10,000 to 50,000 MNT requires low assumptions on the recipient’s economic situation. Attempting to buy a larger percentage of votes therefore would not only require more single payments but also larger individual sums if we assume that the poorest part of the population is usually being targeted.

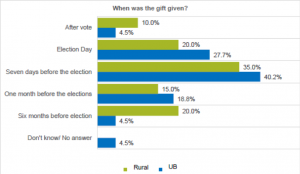

Not surprisingly, the majority of gifts were given in the weeks leading up to the election. The low percentage of after-election gifts might be explained by “if I win, you get something” schemes.

Which parties are involved?

While both major parties seem to have been involved in the practice, the MPP is clearly on top. Although it has to be mentioned that the DP was distributing more voting incentives in the countryside than in the capital.

The fact that nearly 60 percent of respondents knowingly received gifts from the MPP might have a simple explanation though: The MPP had and has by far the most effective and centralized party structure in Mongolia. Since vote-buying is illegal in Mongolia, parties have to organize it covertly. The money or non-monetary gifts have to be raised, stored, and distributed. Furthermore, local aides have to identify potential recipients and avoid law enforcement. Besides these obvious logistical hurdles, parties also have to ensure that the cash that is meant to be handed out is not being pocketed by party members themselves. The constraints that are being dictated by the secretive nature of the endeavour favour highly centralized and more effectively organized parties. Small parties like the MPRP usually neither have the structure to carry out vote-buying on a larger scale nor do they see any usefulness in it. The direct election system that is in place since 2016 limited the most promising candidates in the overwhelming majority of the voting districts to the two major parties. That nearly 15 percent of the respondents cannot tell the political affiliation of the person who gifted them is at least curious.

How effective is vote-buying?

To measure the effectiveness represents the biggest challenge. First, recipients of gifts might not realize themselves if these handouts affect their voting behaviour or they might rationalize these gifts. Second, possible social stigma ascribed to “selling one’s vote” may shame respondents into downplaying the transactional dimension of the gifts. But these are problems that any interpretation of an empirical study has to deal with.

While nearly 8.9 percent of the recipients thought that their vote was “bought” 6.3 percent reported that the attempt to buy their vote had the opposite effect on them. While one should not take these numbers at face value they indicate a trend: Most people receiving gifts do not seem to interpret them as a binding reciprocal agreement. Since “booth selfies” or pre-filled ballot papers are so far not a common practice in Mongolia this evaluation seems to be correct. The practice seemed to have only a marginal direct influence on the last parliamentary elections.

Outlook

No question, (attempted) vote-buying is harmful to any democracy. It undermines trust in the integrity of the election process. It might also swing districts during close races. This kind of electoral fraud and its effects will remain murky to understand at best. But one should not underestimate the agency of voters to remain sovereign actors. An interesting subject for future studies remains if vote-buying might be primarily used to foster supporter mobilization or voter turnout.

Note: The study discussed in this article was completed in September-November 2019 by SICA LLC (www.sica.mn/en) funded by Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation.

About Johann Fuhrmann and Max Duckstein

Johann Fuhrmann heads the office of the Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation in Mongolia. Prior to that, he was Head of Growth and Innovation at the Economic Council (Wirtschaftsrat der CDU). As a scholarship holder of the German Academic Scholarship Foundation he obtained his Master’s degree (MSc.) in International Relations at the London School of Economics.

Max Duckstein is Senior Policy Analyst at the Konrad-Adenauer-Foundation’s office in Mongolia. He obtained his Master’s degree (M.A.) in Sociology at Bielefeld University. As a scholarship holder of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) he spent a semester in Russia as visiting researcher at Saint Petersburg State University.

Follow

Follow