Hello readers!

Last Thursday our ASTU class went to the Archives at the IBLC Library in order to dig deeper into Joy Kogawa’s “Obasan”. I was amazed by the number of archives that were available to us; we had letters from readers, correspondence from editors and friends, letters and drawings from children, several drafts of the book, articles from books and newspapers that mentioned and praised “Obasan” and/or Joy Kogawa, propositions for movies based on the book, historical documents that Kowaga used for research, letters from institutions giving awards to Kogawa for her literary work, etc.

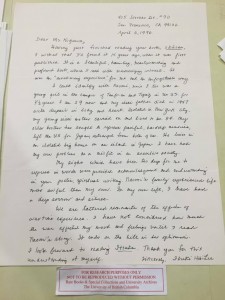

Going through the many folders of correspondence from readers, I came across a letter from a Japanese woman named Ibuki Hibi Lee from April 6, 1996. In her letter she thanks Joy Kogawa for an “awakening experience” because she endured the same fortune that Naomi and her family did. Ibuki was young girl when they took her with her family to the camps in the U.S. for three and a half years. In a heart-felt letter she tells Joy about her family; about how her dad died in 1947 with despair in body and heart, how her mother carried on with her life and lived to be 84 years old, and how her brother fought hard to repress the memories and left the U.S. for Japan in order to live in an isolated big house on an island.

“My sighs which have been too deep for me to express in words were provided acknowledgement and understanding in your poetic, spiritual writing”. This quote from Ibuki’s letter makes me think of all the people that went through a similar situation in the camps in the U.S. and Canada, but also the people that went to the concentration camps during WWII. I wonder about how these people were in such a state of shock after they got out of the camps that they couldn’t even process what had happened. They couldn’t even talk about what had happened because the trauma was too strong, the pain was too much for them to bear. Ibuki illustrates this aspect of the aftermath when she says: “In my life I have had experienced a deep sorrow and silence”. In our ASTU class we talked about how silence can be a way to communicate our emotion; how the absence of words doesn’t mean that we have nothing to say or that we don’t feel anything, on the contrary, the absence of words simply indicates that the trauma cannot be expressed in something as simple as words. In fact, in Kogawa’s “Obasan”, Aunt Emily is constantly talking and overwhelming everyone with everything she has to say, whereas Obasan remains silent through most of the book because sometimes there are things that are better left unsaid, and because silence was her way of coping with everything that she went through.

Moreover, Ibuki makes one last reveal when she tells this to Kogawa: “I have not considered how much the war affected my mood and feelings until I read Naomi’s story”. I found this quote to be really heart-breaking because of everything that it implies. This quote suggests everything that every person that went through similar traumatic experiences feels; it portrays the denial that they lived in, the resentment towards the people who oppressed them, the pain that they had to suppress in order to move on with their lives, and the frustration of losing not only their families and their properties, but the precious years that they won’t be getting back.

Ultimately, Obasan serves as a reminder of the unfair treatment that Japanese-Canadian people had to bear at the times of World War II. These people were discriminated and scrutinized by the government and society because of their heritage, which led to these people actually denying their heritage in the long run and feeling embarrassed of where they came from in order to be accepted in the place that they had the right to call home.

Thank you for reading. I hope you enjoyed it!

CITATION: Lee, Ibuki. Letter from Ibuki Hibi Lee to Joy Kogawa. 6 April 1996. Box 13 File 8. Joy Kogawa fonds. University of British Columbia Library of Rare Books and Special Collections, Vancouver, Canada.