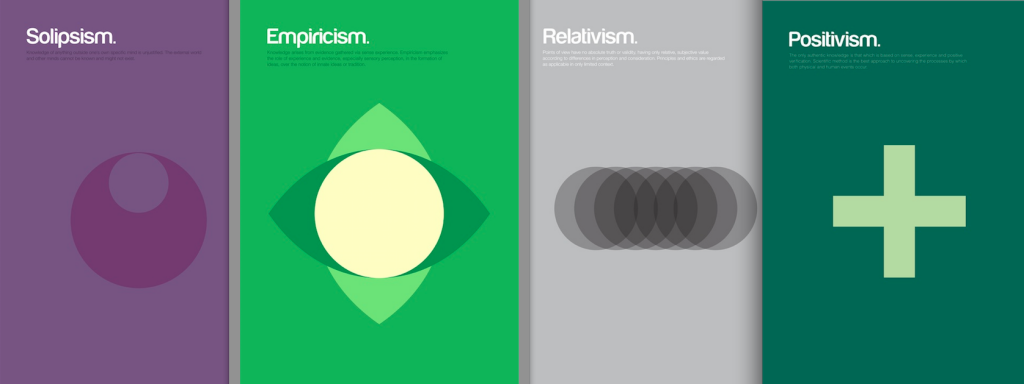

The Philographics: Big Ideas in Simple Shapes is a novel, delightful representation of core ideas in philosophy, many of which underpin the research enterprise. For some folks, the images may capture what otherwise takes volumes to explain.

Category Archives: big abstract ideas

Critical research ~ excellent bibliography to get you started

To explore the theoretical basis and some examples of critical research this bibliography is an excellent starting point.

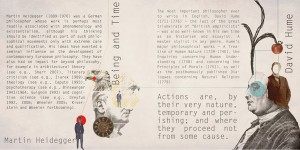

Epistemology ~ artfully rendered

Julissa Lopez uses collages to illustrate the thinking of those who have deeply influenced the ways knowledge is conceptualized. Kant, Hume, and others’ thoughts are rendered artistically.

post-positivist and social constructionist perspectives on research

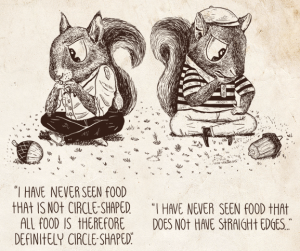

An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool. — Richard P. Feynman

In addition to being amusing, this little book is a great introduction to argumentation and more specifically the various common errors in logic. From hasty generalizations (see cartoon) to appeals to irrelevant authorities to straw man arguments, each is described with examples and a clever cartoon as illustration. Scholarship always involves making arguments and budding scholars might find this useful in honing their skills.

In addition to being amusing, this little book is a great introduction to argumentation and more specifically the various common errors in logic. From hasty generalizations (see cartoon) to appeals to irrelevant authorities to straw man arguments, each is described with examples and a clever cartoon as illustration. Scholarship always involves making arguments and budding scholars might find this useful in honing their skills.

The ethics & politics of research ~ Napoleon Chagnon will not go away

For decades now controversy and acrimony have swirled around Napoleon Chagnon, the anthropologist who studied the Yanomami living in the rainforests of northeastern South America’s Orinoco Basin. I read Chagnon’s work as an undergraduate and recall that the work was titillating, but even then understood his work as a reflection of an age old approach in cultural anthropology to see cultural groups through an evolutionary lens, progressing from simple (usually meaning hunting and gathering economies) to complex (industrial or us).

What I didn’t quite appreciate at the time was the evolutionary biological and genetic conclusion Chagnon drew ~ that described the Yanomami as “the fierce people” who are the iconic example of the innate, natural state of humans ~ a state of chronic warfare and homicidal violence.

What I didn’t quite appreciate at the time was the evolutionary biological and genetic conclusion Chagnon drew ~ that described the Yanomami as “the fierce people” who are the iconic example of the innate, natural state of humans ~ a state of chronic warfare and homicidal violence.

Among anthropologists, Chagnon’s conclusions have been discredited, a case of serious over-reaching from the data. (See, for example, the Survival for Tribal Peoples for much more detail about the discrediting of Chagnon’s conclusions.) His work has value primarily as an example of what not to do if you want to do good ethnography, a methodological counter-example if you will. Marshall Sahlins coined the term research and destroy to characterize situations where anthropologists are complicit with colonial, military interests and he describes how Chagnon’s work with the Yanomami falls into this category. More broadly the negative impact of anthropologists in South America has become an important ongoing controversy that pivots around Patrick Tierney’s book, Darkness in El Dorado: How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon.

In spite of a thorough critique within the discipline, Chagnon continues to hold sway. Those who continue to laud his work see the critics as anti-science. His competence as an anthropologist is questionable yet he rumbles on and his new book Noble Savages is being promoted in the mainstream media. This book is as much an attack on anthropology as a further elucidation of the Yanomami peoples, a point Elizabeth Povinelli makes in her review of the book. While Chagnon’s book fuels the flames of this decades old controversy, his election in 2012 to the National Academy of Sciences serves to exonerate him and celebrate his work. Chagnon’s election to the NAS has provoked a resignation from the NAS by Marshall Sahlins, also a prominent anthropologist.

Historically, academic disciplines go through periods of upheaval, intellectual dust ups that sometimes result in Kuhnian paradigm shifts. The Chagnon story may be a pivotal event around which anthropology makes such a shift… but this paradigm shift, if that’s what it is, continues to play out slowly and acrimoniously. Time may tell.

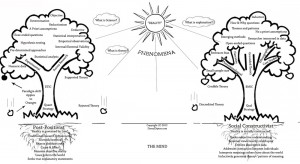

Introduction to ontology & epistemology

Language matters

For an ongoing discussion of the way language matters, check out The Little Blue Blog, a compilation of brief analyses of how issues about public policy are framed, especially as undergirded by particular conceptions of democracy. Bloggers George Lakoff and Elisabeth Wehling describe the blog:

The Little Blue Blog is a continuation of The Little Blue Book: The Essential Guide to Thinking and Talking Democratic. The book addressed a problem that progressives face everywhere: conservatives have framed just about every issue in conservative moral terms. Progressives all too often find themselves stuck with using conservative language and ideas, which reinforces those ideas even in arguing against them. The Little Blue Book tells how to get out of the trap. Use the progressive moral system you believe in. This is about much more than words. Words mean things. You need to say what you believe and what is true. Progressive communication is democratic communication. It requires that you be transparent, authentic, honest, and strong if your fellow citizens are to trust you. This is advice for all citizens, not just our leaders.

In a description called ‘framing the issues’ Lakoff & Wehling give a short lesson in frames… the ways in which ideas are clumped together so that things make sense to us. In particular, “Frames are structured in a hierarchy. To understand a kitchen, you have to understand food preparation and eating. In politics, the highest frames are moral frames. The reason is that all politics is moral: political leaders propose policies because they are right — not because they are wrong or don’t matter. All policies, therefore, have a moral basis.” As such, ‘facts’ and ‘logic’ have significantly less purchase then we think in determining what and how we believe and think.

This blog is a continuation of The Little Blue Book, and both are meant to school Democrats and progressives on how to use language and frames more effectively within public discourse about policy issues. Lakoff & Wehling follow their own advice in this discourse by making their own moral frames the basis for their discussion.

This blog is a continuation of The Little Blue Book, and both are meant to school Democrats and progressives on how to use language and frames more effectively within public discourse about policy issues. Lakoff & Wehling follow their own advice in this discourse by making their own moral frames the basis for their discussion.

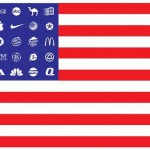

the power of metaphors

We are, of course, aware of the power of metaphors, but we often simplistically believe that we choose the metaphors we use rather than them being embedded within metaphors that are so deep (and often simple) that we misunderstand their power and their hegemony. Lakoff and Johnson have provided an excellent analysis of this idea in Metaphors We Live By and Lakoff has contributed significantly to our understanding of the role of metaphors in public policy and discourse, often employed by the media and politicians.

We are, of course, aware of the power of metaphors, but we often simplistically believe that we choose the metaphors we use rather than them being embedded within metaphors that are so deep (and often simple) that we misunderstand their power and their hegemony. Lakoff and Johnson have provided an excellent analysis of this idea in Metaphors We Live By and Lakoff has contributed significantly to our understanding of the role of metaphors in public policy and discourse, often employed by the media and politicians.

In an editorial on the fiscal cliff, Lakoff illustrates the ways the fiscal cliff metaphor is constructed through other more deeply held metaphors. Here is an excerpt:

Let’s take a look at the metaphorical complexity of “fiscal cliff” and how the metaphors that comprise it fit together. The simplest, is the metaphor named MoreIsUp, which is a neural circuit linking two distinct brain regions, one for verticality and one for quantity. It is a high-level general metaphor widespread throughout the world, and occurs in a vast number of sentences like “turn the radio up,” “the temperature fell,” and so on.

The economy is seen as moving forward and either moving up, moving down or staying level, where verticality metaphorically indicates the value of economic indicators like the GDP or a stock market average. These are indicators of economic activity such as overall spending on goods and services or the sale of stocks. Why is economic activity conceptualized as motion? Because a common conceptual metaphor is being used: ActivityIsMotion, as in sentences like “The project is moving along smoothly,” “The remodeling is getting bogged down,” and so on. The common metaphor TheFutureIsAhead accounts for why the motion is “forward.”

In a diagram of changes over time in a stock market or the GDP, the metaphor used is ThePastIsLeft and TheFutureIsRight, which is why the diagram goes from left to right when the economy is conceptualized as moving “forward.”

When Ben Bernanke spoke of the “fiscal cliff,” he undoubtedly had in mind a graph of the economy moving along, left to right, on a slight incline and then suddenly dropping way down, which looks like a line drawing of a cliff from the side view. Such a graph has values built in via the metaphor GoodIsUp. Going down over the cliff is thus bad.

The administration has the goal of increasing GDP. Here common metaphors apply: SuccessIsUp and FailingIsFalling. Hence going over the fiscal cliff would be a serious failure for the administration and harm for the populace.

These metaphors fit together tightly in the usual graph of changes in economic activity over time, together with the metaphorical interpretation of the graph. From the neural perspective, these metaphors form a tightly integrated neural cascade — so tightly integrated and so natural that we barely notice them, if we notice them at all.

What is equally important about Lakoff’s illustration is that one metaphor, especially one built on more deeply cognitively embedded metaphors, cannot be easily replaced (if at all) by an alternate metaphor.

Using film clips for teaching

The Sociological Cinema is a website of film clips that can be incorporated into teaching about a wide range of sociological topics. Videos are usually available on YouTube or some other site and might be clips from popular TV shows/movies, or made specifically as videos on a topic.

The site has a search function, and you can submit suggestions for videos, resources and assignments to be added to the site. Just a couple examples are:

Cultural jamming…

Norm breaching…

There isn’t a huge amount of content on the site yet, but it has a lot of potential.

Follow

Follow