In The World is Moving Around Me, Dany Lafarriere often makes reference to Port-au-Prince as an artistic capital of the world. He refers to how when everything else falls apart, culture remains. Throughout the book Haitian art is placed within the context of a history of hardships, and in a sense growing out of this history. In the chapter “A City of Art,” he argues for turning “Port-au-Prince into a city of art” within the process of rebuilding (122). Here he sees the an opportunity not to re-write history, but to change the landscape to visually represent what he – as part (or at least he used to be) of the Port-au-Prince artistic circle – sees as such a vital part of Haitian culture. He says “Despite our troubles, our culture is joyful; we need to show it off” (123). The way I see it here, Haitian art is not only about resilience, but also pride in a world that often projects a very one-sided perspective of the country (something he attempts to dispel throughout the text). Frankétienne represents this attempt “to turn this disaster into a work of art” (113), the symbol of the resilient Haiti that continues to grow and does not let itself be shaped by the disaster, but rather use the disaster to shape his own vision. This is cultural creation as agency.

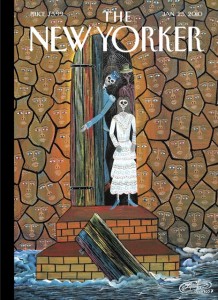

This made me think of the great Haitian surrealist painter Frantz Zepherin, who has made beautiful paintings of Haiti after the earthquake. Here is a good article on his art and a US exhibit in 2010 called “Art and Resilience.” You can find all the paintings from that exhibit online here. One of his paintings was featured on the cover over the New Yorker in 2010, which greatly differs from the Demers’ photograph we saw in TIME. In an article for the Smithsonian, he describes the exigence to paint he felt right after the earthquake hit: “That night, I decided I had to paint…So I took my candle and went to my studio on the beach. I saw a lot of death on the way. I stayed up drinking beer and painting all night. I wanted to paint something for the next generation, so they can know just what I had seen.” The entire article is really worth reading because I think it does a good job at avoiding the disaster clichés of a post-Earthquake journalism by focusing specifically on a couple of painters, their personal stories in their own words, and how they are dealing with the disaster in their own terms. We might want to think of how a more narrow lens (perhaps “more specific” is a better way of explaining it) relates to Lafarriere’s balance of personal narratives within a public event.

Earthquake Timer

Humanitarians and Soldiers

Ground Zero

Interpellation of the Great Spirits for the Saviour of the Country

New Yorker Cover