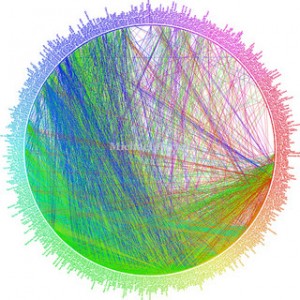

FaceBook Friends Network Visualization. CC Image Source: Michael Porter (Libraryman). Available: http://www.flickr.com/photos/libraryman/3703100645

In his oft-quoted and prescient article in The Atlantic Monthly, Vannevar Bush (1945) ponders what project US scientists might turn their attention to in the post-war period. He argues that the most important challenge is finding meaningful ways of navigating the vast human record:

There is a growing mountain of research. But there is increased evidence that we are being bogged down today as specialization extends. The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers—conclusions which he cannot find time to grasp, much less to remember, as they appear. Yet specialization becomes increasingly necessary for progress, and the effort to bridge between disciplines is correspondingly superficial.

Professionally our methods of transmitting and reviewing the results of research are generations old and by now are totally inadequate for their purpose. If the aggregate time spent in writing scholarly works and in reading them could be evaluated, the ratio between these amounts of time might well be startling. Those who conscientiously attempt to keep abreast of current thought, even in restricted fields, by close and continuous reading might well shy away from an examination calculated to show how much of the previous month’s efforts could be produced on call. Mendel’s concept of the laws of genetics was lost to the world for a generation because his publication did not reach the few who were capable of grasping and extending it; and this sort of catastrophe is undoubtedly being repeated all about us, as truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential.

The difficulty seems to be, not so much that we publish unduly in view of the extent and variety of present day interests, but rather that publication has been extended far beyond our present ability to make real use of the record. The summation of human experience is being expanded at a prodigious rate, and the means we use for threading through the consequent maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of square-rigged ships. (Bush, 1945)

25 years later, in Future Shock, Alvin Toffler returns to the question posed by Bush. He comments on the marked success of speed reading schools in the wake of the accelerating rate of communication and publication: “busy people wage a desperate battle each day to plow through as much information as possible” (Toffler, 1970, 168). Notably, phrases such as “information explosion” and “knowledge explosion” may be traced to the mid-1960s and early 1970s — the time in which Toffler was writing about “future shock,” a phrase he uses to describe “the shattering stress and disorientation that we induce in individuals by subjecting them to too much change in too short a time” (2).

33 years later, post-Internet, the rhetoric is remarkably unchanged. James Morris equates the problem of coping with exponentially growing stores of information to the problem in wealthy agricultural nations of coping with an overabundance of food. He writes as follows:

Reliable food production also brought a smaller, but real problem: obesity. Evolution has not yet told our hunter-gatherer bodies that the food supply is dependable. We carry months’ worth of food in the form of fat. More people in our modern societies die from obesity than from starvation.

Similarly, the plenitude of information has brought about a new disease: infobesity. Newspapers, magazines, television and the Internet are producing far more information than we can absorb. Now, no one is being bombarded, i.e. forced to absorb information they don’t want; but information seduces us into ingesting too much, just like food. The Internet, by getting all this information in the same place and accessible to computers, offers some the hope that we’ll be able get control of the information glut. But that’s an illusion. (Morris, 2003, n.p)

Morris’s consumer model casts knowledge as something that is ingested and stored, and overindulgence in knowledge as a medical condition that needs to be managed. Evidently this is a markedly different casting from models of knowledge mobilization that frame information as material for and the material of sharing, exchange, remix, mashup, play, participation, and so on.

Regardless of how the problem has been framed through the past seventy years, it is evident that an important recurring question of technology for knowledge mobilization — and such technology includes everything from scrolls to books to computers — concerns the vast extent of the human record and how it might be managed. What does it mean to be educated in the information age? What does it mean to be “well read”?

Franco Moretti (2000), an American world literature scholar who has faced the tyranny of the English literary canon for decades, observes that traditional approaches to managing knowledge have privileged select texts and promoted learning methods that encourage deep knowledge of these select texts to the exclusion of a whole range of other valuable knowledge artifacts (see the quote at top right). He argues that we would do well to interrogate such elitist approaches in favour of more inclusive strategies. Ultimately, the question he raises might be framed thus: might digital media enable ways of ‘panning back’ — of changing our perspectives on knowledge to enable novel understandings?

Stan Ruecker would say this is indeed a key affordance of digital media. He advocates for greater implementation of “rich prospect browsing,” or the development of browsing environments wherein “some meaningful representation of every item in a collection is combined with tools for manipulating the display” (Ruecker, 2006, n.p.; see also Ruecker, Radzikowska and Sinclair, 2011). The idea is that different visualizations of the information under consideration, whether that knowledge consists of millions of books, or words in a single book, or numbers, or points of connection between FB friends (see, for example, the image at the start of this post), may be helpful in providing unique perspectives, which in turn may generate novel understandings. In promoting this approach, Ruecker cites Jorge Frascara (2006) from the field of visual communication design, who observes that the desire to gain a sweeping view of one’s surroundings — whether the surroundings are physical or intellectual — is a fundamental human urge: “We need so much to see what surrounds us that the sheer fact of seeing a wide panorama gives us pleasure.”

Video: Stan Ruecker on Rich-Prospect Browsing. Source

In this session we’ll examine some of these ideas and perhaps take a brief trek part way up the growing mountain of of the human record to consider the affordances and limitations of different perspectives on knowledge.

Works Cited

Bush, V. (1945). As We May Think. The Atlantic Monthly. 176(1), 101-108. Available: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/3881/

Frascara, J. (2006). Introduction: Creating communicational spaces. Designing Effective Communications: Creating Contexts for Clarity and Meaning. Ed. Jorge Frascara. NY: Allworth Press, xiii-xxi.

Morris, J. (2003, March 30). Consider a Cure for Pernicious Infobesity. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Available: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/tales/infobesity.html

Ruecker, S., Radzikowska, M. and Sinclair, S. (2011). Visual Interface Design for Digital Cultural Heritage: A Guide to Rich-Prospect Browsing. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

Ruecker, S. (2006). Experimental Interfaces Involving Visual Grouping During Browsing. Partnership: the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 1(1), n.p. Available: http://journal.lib.uoguelph.ca/index.php/perj/article/view/142/177

Toffler, A. (1970). Future Shock. New York: Random House.