Narrative 1: Freedom Sight

![]()

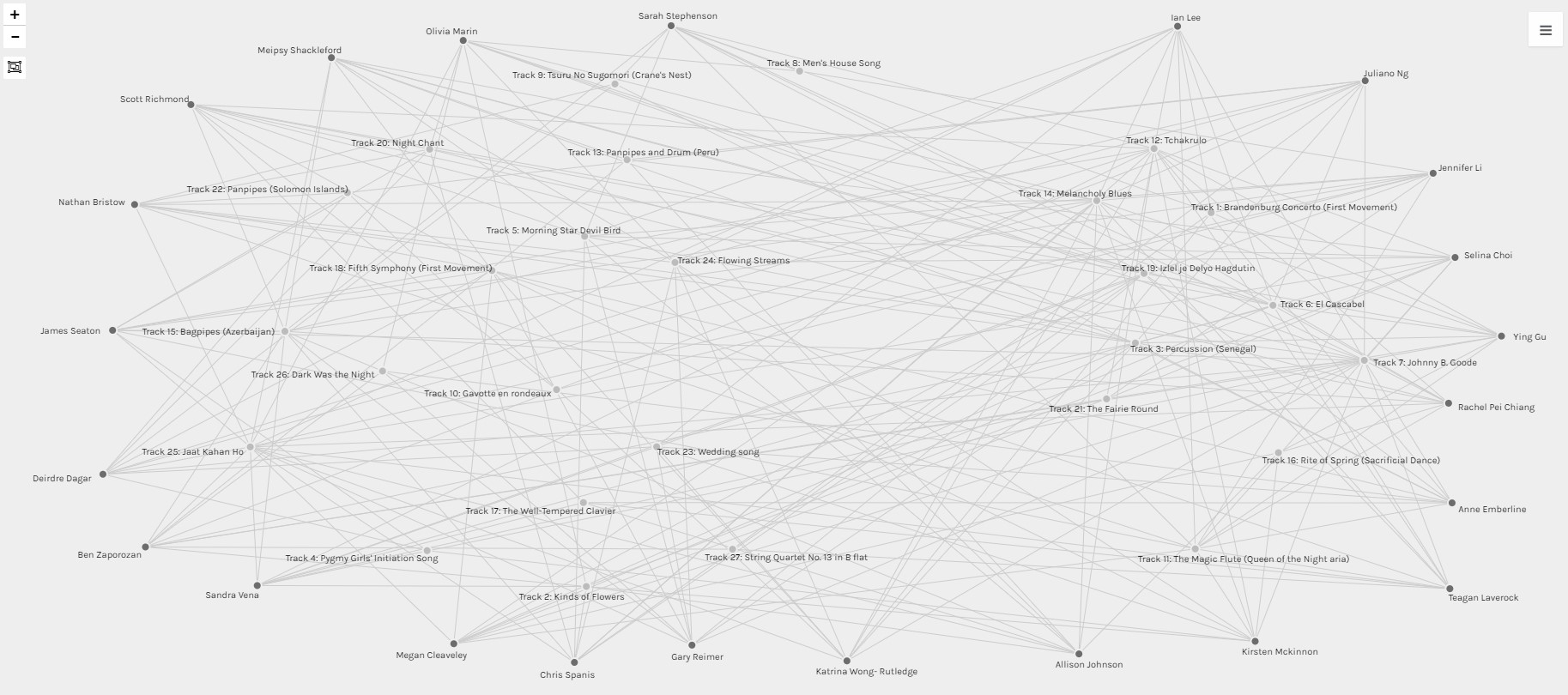

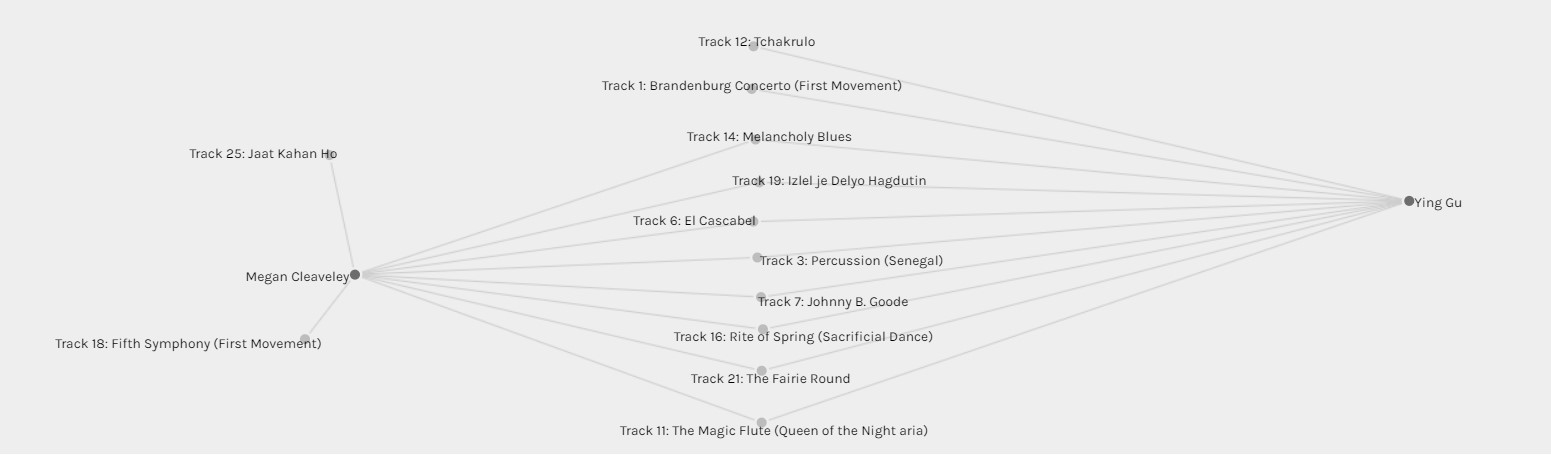

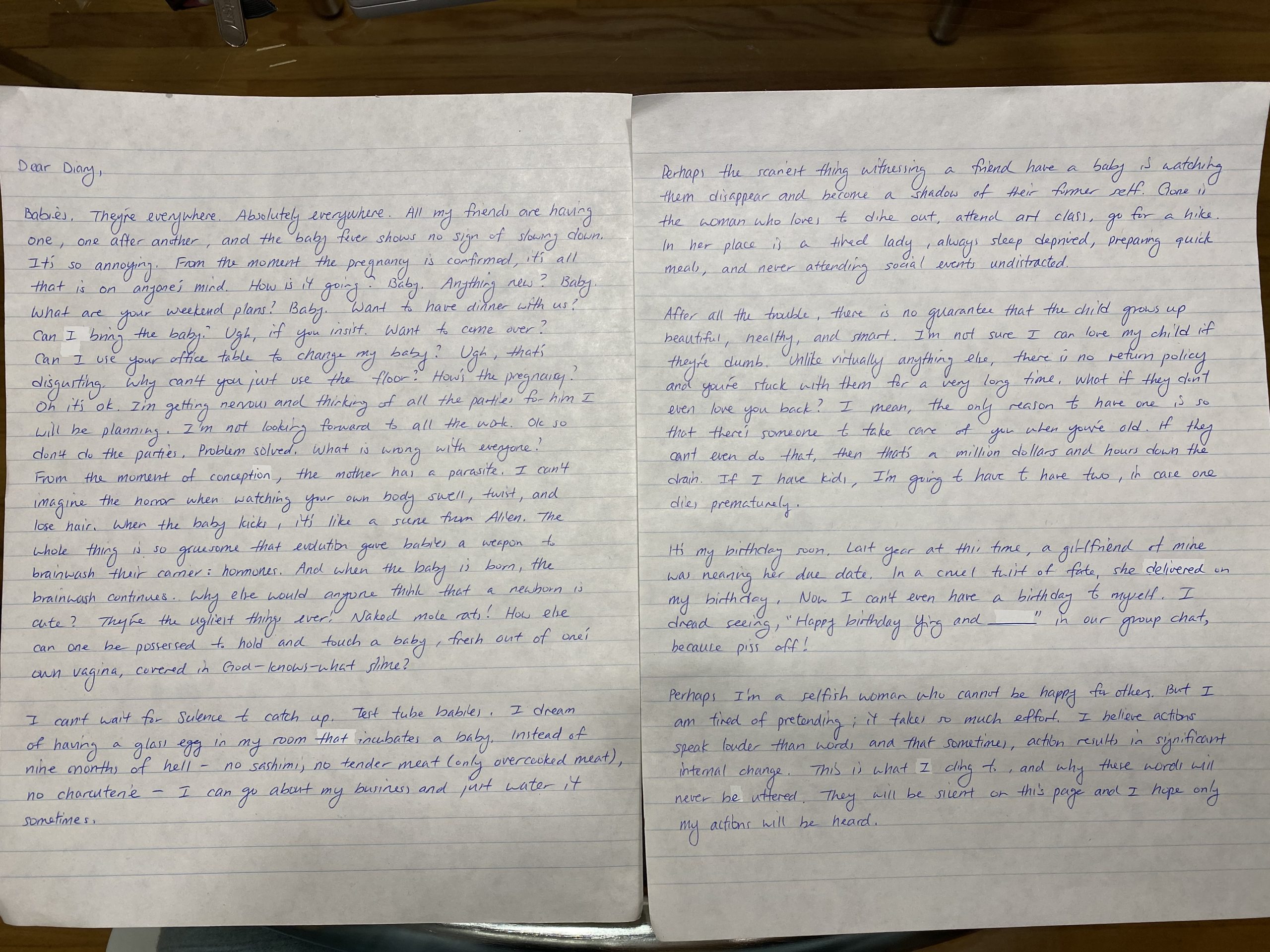

In the early 20th century, ads were everywhere and it only seemed like they would become increasingly invasive in people’s lives. There was no way to turn them off in public spaces — Facebook, Instagram, billboards that one must cross — and spaces where they can be turned off came at a cost (click here for the article, Attention Dictatorship in the Early 20th Century). It took another 60 years for people to raise the question, is it ethical that the freedom of vision is not guaranteed when so many other personal freedoms were? It was an absurd period in history where the freedom to bear arms in the former United States of America (click here for the article, The Dissolution of the United States) was so fought for, along with the freedom of speech, including hate speech, while people’s attention economy was at the complete mercy of big companies. Multiple studies revealed that ads were shaping decisions, behaviours, and values in profound ways (click here for the article, Are Your Thoughts Yours? and Why Flat Earth Believers Surged in 2028). Arguably, the most publicized UN Supreme Court case, Martin vs. Instagram, pushed public demand for governments to instate freedom of vision (click here for the article, Why Judge Corseau ruled that Martin’s Heart Attack was Instagram’s Doing). What followed this historic case was the #righttovision movement on social media (click here for the article, Why Sally Gauged her Eyes Out). And yet, governments failed to make any changes to regulate ads. And why should they when they were being lobbied excessively by companies who were making money off of ads, who were simultaneously targeting favourable ads to government officials? The final straw was when textile giant, Fabricate, began selling time on their infits to companies, after 25 years of giving its users 100% control over the content on their clothes (click here for the article, The Unraveling of Fabricate). For our younger readers, there was a time when clothes were static. Such items were called ‘outfits’ (click here for the article, Top 10 Infit Downloads). It came at no one’s surprise when companies like Freedom Sight and Vision Void began to crop up all over the world, offering services to eliminate ads in ways that AdBlock on browsers never could. Freedom Sight and Vision Void, the two giants in the industry competed until 91% of the world’s population had one of their implants. A Red Queen dynamic quickly ensued between companies developing new technology and new methods of ad delivery (click here for the article, IR and UV Ads) and Freedom Sight and Vision Void developing better recognition and blocking technology in their implants. And now, we arrive at the world’s current predicament. What is to be done about the thought disparity between those who can and those who cannot afford to block ads? (click here for articles, Children Without FV/VV Implants Are Less Creative, Should Politicians Without FV/VV Implants Be Elected To Office, Blindness On the Rise from Black Market FV/VV Implants, and Should Babies Receive FV/VV Implants?).

Jane Foley received her implant from Freedom Vision when she was 30 when she sold her great-great grandparents’ antique, non-self driving car, for $50 000 to a collector, and could afford a tier 3 implant. Until then, she lived her life immersed in the ad world. Only 5% of individuals receive their implants after the age of 15. Thus, Jane has a unique ability to reflect and understand the experiences of implanted and non-implanted people. She has been with Pacific Review for 9 years as a reoccurring guest journalist.

———————————————————

Narrative 2:

Utopia

From Songs from Ustralia, 2061

It began with the rise of the mighty

The rise of the tiny

The rise of the mighty

One small bite and you get a nasty

It really is ghastly

It really is nasty

Tick tock, tick tock

Small bite, impact of a Glock

And you wonder why you ever left your block

To go into the woods, tick tock, tick tock

What used to smell so wonderful

Now warns of something so harmful

What used to cause the mouth to water

Now you double over and falter

Just one taste, it’s ok, you will survive!

Just one bite, it’s ok you will revive!

No such thing, covered in hives

No such thing, the new age arrives

It began with the rise of the mighty

The rise of the tiny

The rise of the mighty

One small bite and you get a nasty

It really is ghastly

It really is nasty

An idea! Problem solved!

Us humans will be evolved!

Convert the compound into aerosol!

It just may save the planet, and us all!

And so in secret, the compound was bred

And so in secret, the compound was spread

Into the water, into the wind

It landed in the eyes and on the skin

Just one taste, surely you’ll survive!

Just one bite, surely you’ll revive!

No such thing, covered in hives

No such thing, the new age arrives

And so ranches became branches

And pens became cleanses

Steaks became dates

And chops became crops

Goodbye polluting farming

Goodbye global warming

Hello healthy living

Hello arteries clearing

That smell that was so wonderful

What was it, we are forgetful

That red that made our bellies full

What was it, we are forgetful

It was built on the backs of the mighty

With the strength of the tiny

The secrets from the mighty

One exposure and you get a nasty

Is it really ghastly?

Is it really nasty?

This Utopia?

———————————————————

Reflection: I began this narrative by contemplating this thought in Dunne & Raby (2013), that problems that seem unsolvable can only be approached by changing our values, attitudes, and behaviour. I can think of no bigger problem than climate change and how unsuccessful one solution is — eat less meat. By eating less meat, we would produce less greenhouse gases and use less land in the raising of livestock. Although veganism is trending and a significant number of people know about this solution, little is done. This is because it is difficult to change our attitudes and values around diet. I mean, meat just tastes so good; I made roast for dinner. We are a consumer society and “it is through buying goods that reality takes shape” (Dunne & Raby, 2013, p. 37). Because the demand for meat is always present, abolishing the livestock industry is a “rejected reality”.

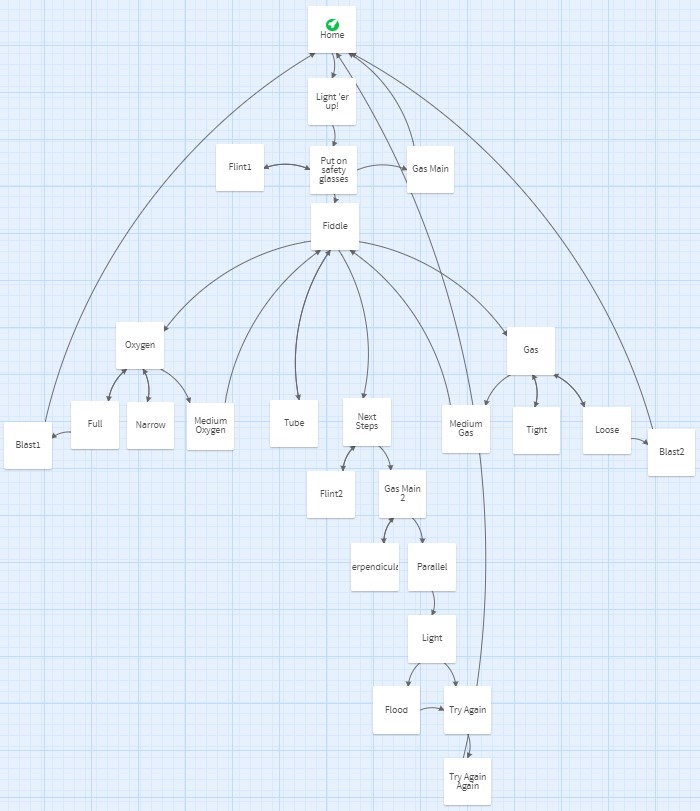

So how do we move the immovable object that is our cravings? Well, instead of focusing on how to change attitudes and values, what if we just eliminate the attitude and value altogether? What if we could design a way to make people get physically sick upon ingesting meat? Surely, the demand for meat would decrease. This technology, would fall under the “possible” cone in Dunne & Raby’s (2013) potential future diagram. Such technology may not be plausible due to the hurdles in ethics (is it ethical to force people to dislike something?), it may not be “probable”, and it certainly is not “preferable” by the individual who would like to continue to enjoy their steaks and bacon. Technology does not always have to be “good” to start, but perhaps it could be good in the long run if the results are overwhelmingly beneficial to humankind. I envision a world with this dark design whereby the most effective ways of change — protests, boycotts, and critical consumerism — are forced (Dunne & Raby, 2013). If an ideal society is a sustainable one, then our current reality where meat is not only consumed, but overconsumed, is an absolute failure.

My poem was inspired by the news article, “Red Meat Allergies Caused by Tick Bites are on the Rise” and a CBC video. The ticks are referenced in the poem as “the mighty” and “the tiny” as such a small creature can cause huge behaviour changes in a person. They are also referenced in the line “tick tock” which alludes to the time between a tick bite and the onset of symptoms, and the time between a bite of meat and the onset of an allergic reaction. At the end of the poem, “the mighty” refers to the scientists who made the decision to use the compounds in a tick bite to change the human population. They must have endured a heavy ethical burden. I imagine that this speculative event took place after global warming became even more pronounced than it is now. The scientists enacted their solution to the problem in Australia where the compound’s spread could be limited to just one continent. Initially met with anger, citizens quickly realized that the outcome was pretty beneficial for the environment and their health. The solution was eventually embraced and red meat was forgotten. Australia became Ustralia as people began to put themselves at the front and center of solving the climate crisis. It also signifies the removal of cattle ranches because beef is graded with the letter, A.

———————————————————

References

Dunne, A., & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: The MIT Press.