Bunsen Burner

Click above to download the .zip file.

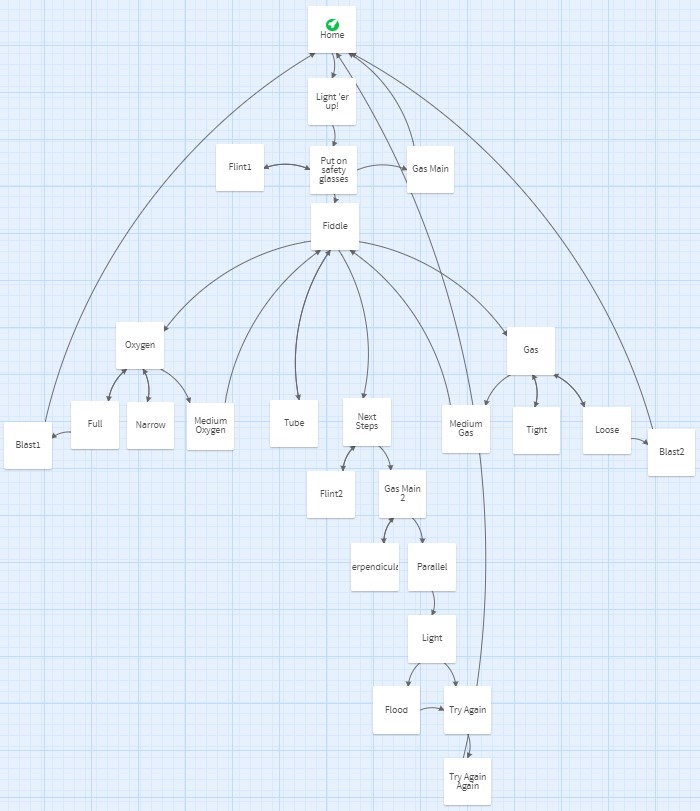

I am a terrible storyteller, so I decided to make an educational game, a simulation to prepare students to use the Bunsen burner safely. I added visuals and sounds to make the experience as real as possible and tried to be funny to make the game enjoyable. As the simulation is intended to mimic the lab, I set most of my links to be decisions. I created good decisions and poor decisions so that students can experience both success and failure. The simulation gives students a safe place to fail and opportunities to remake erroneous decisions.

At the start of designing the game, the process was relatively straight forward. There is definitely a starting point to setting up the Bunsen burner – connecting the rubber tube to the gas outlet – so I created a list of decisions around that. Hierarchies and sequential steps are a large part of learning science and so beginning my Twine design in this same way felt natural. Having decisions be the links set the expectation that the linked page will be about the resulting consequence of an action. To reinforce that page B is the result of what was decided on page A, I set a welcome message on page B to remind students of their decision that led to the result (Bolter, 2001).

I had expected that the remaining steps in setting up a Bunsen burner be sequential as well, but to my surprise, they were not. I realized that the following steps, adjusting the oxygen and gas valves on the burner, can be done in any order. In fact, when I set up the burner myself, I am just as likely to adjust the oxygen valve first as I am to adjust the gas valve. And so, my Twine game narrative was no longer linear, but had parallel pages, and this, to my surprise, also reflected my focus and thinking process. In this fork of my narrative, I started to have rapid fire thoughts about both valves and the decisions for each simultaneously. At the same time, in the middle of my coding, I decided to incorporate sounds and images. I would frequently interrupt my own coding to run into the lab to take a picture or to record a sound. My mind indeed operated by association at this point; as soon as one thought occurred, my mind snapped instantly to another that is associated with the first thought (Bush, 1945).

Upon further reflection, is connecting the rubber tube actually the first step in setting up the Bunsen burner? One could just as easily check the valves first. The cognitive structures in my brain are a web of trails (Bush, 2001) that are made linear when memories are accessed. However, the linearity is different each time. One day, I may check the oxygen valve first, then the gas, then connect the tube. On another day, I may do the complete reverse of these steps. At this point, I deleted all the arrows in my Twine, and reconnected the pages so that connecting the tube to the gas outlet was no longer the mandatory first step.

So if our thoughts are webs, why are we so obsessed with teaching sequentially? Why are our subjects organized into units and our notes labeled with numbers and indexed? I think there is a difference in how information goes into the brain and how information is stored and accessed in the brain. If information is stored linearly, like if our brain was a big scroll, it would take much longer for us to find and recall information. It is much more efficient for ideas to be stored as a web, with each idea hyperlinked to many others. But, in learning new ideas, linearity may reign supreme. Learning is already a difficult task. I cannot imagine learning history from multiple points in the timeline simultaneously or learning chemistry by jumping around from atomic theory to the mole. Information must be presented in an organized way so that students can first understand the topics, and then hyperlink them to their own existing web. Only they can make sense of new information within their own contexts. Each student arrives to class with their own internal memex; only they have access to the levers and buttons.

Bolter, Jay David. (2001). Writing space: computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bush, V. (1945). As we may think. The Atlantic Monthly, 176(1) (Links to an external site.), 101-108.

This Twine is so great and I think a really good example of how a Twine can be used as a tool to transmit information. I can also see how you could have students use it to demonstrate their knowledge. So for example instead of them completing this Twine before beginning a laboratory, you could ask them to create their own Twine to demonstrate how to use a Bunsen burner. I recognize that you might not actually have them do such a time consuming task for Bunsen burner, safety but maybe for like maybe general lab safety at the beginning of the year? Or even have them use a Twine for a final project on a science concept like circuits?

I also really appreciate how you explained the way that creating the twine elucidated your thinking processes.

Hi Deirdre!

Thanks for playing my Twine! You know what, I think having students make a lab safety Twine is a great idea! I think in the junior sciences, we would have the time. Senior classes are a bit tight with all that content we have to cover.

Hello Ying,

I thoroughly appreciated how neatly you arranged your entire twine outline! This likely made it much easier to edit and review your work, and as you identified, showcased the parallel pathways that students could take in setting up their lab work. Just like with math, I encourage students to be thinking of parallel pathways, or multiple strategies, that enable them to calculate their way to the final answer (and to be non-rigid in using only one strategy).

And in ‘parallel’ (hah!) with chemistry, certain steps are sequential, but there is room for students to make decisions based on their comfort and preference.

Hi Ian,

Ha, thanks for appreciating my organization! I think with our math backgrounds, we tend to be more organized thinkers. We just learn better when information is laid out sequentially. Can you envision a hypertext for math? Oh my goodness, I would go insane.

Hello Ying,

I really liked when you stated “If information is stored linearly, like if our brain was a big scroll, it would take much longer for us to find and recall information”. I wonder if that’s the thinking that went into creating sheet music? I remember when I first started taking drum lessons, my instructor told me that some of his students can’t read sheet music, so he has to write drum tab out for them (simplified sheet music if). He told me that when one of his students comes to the lesson, they have to set up three music stands to lay the long sheet across them. Similarly, if information is stored in chain of associations in our brain, or on screen through hyperlinks, we don’t have to sift through the knowledge library (Bolter, 2001) to find what we are looking for.

Hi Jennifer,

Hmm, I think music needs to be linearly represented if you are trying to play a specific piece. The linearity confers chronology. Though, how fascinating it would be to compose a piece of music where the player could choose which route to take. Would that be like, having a 3×3 music grid where the player can choose which page to move on to after finish each page?