Story

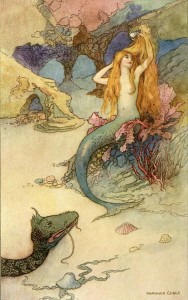

Long ago, when the world was made up of water and islands, there were many rocky shores on which it was traditional for mermaids to sit, and almost as many mermaids to sit on them. Their chief pursuits were to sun themselves, to admire the picturesque sight of the other mermaids atop their rocks, to comb their hair, to collect sea shells, to hold philosophical conversations with the starfish, and, of course, to sing.

The mermaids loved singing with their friends. They would compose great operas on the topics of salt spray and wind and the slithering waves. It must be said that the mermaids were not always in tune, and they did not always understand the concepts of “melody” and “harmony” in quite the way that you or I would. They also got a bit carried away from time to time. Still, they loved singing, and were very proud of their music.

Now one day, when the mermaids were preparing to begin a great opera on the topic of sunlight glinting on the waves, it happened that a young sea monster had become lost and was trying to remember the way to the nearest southern current. Noticing the assembly of mermaids, the young sea monster crept closer—her kind were a solitary bunch, and never having seen a mermaid before, she was curious to investigate the strange creatures. She was only a dozen feet from the shore when the mermaids began their opera.

Now one day, when the mermaids were preparing to begin a great opera on the topic of sunlight glinting on the waves, it happened that a young sea monster had become lost and was trying to remember the way to the nearest southern current. Noticing the assembly of mermaids, the young sea monster crept closer—her kind were a solitary bunch, and never having seen a mermaid before, she was curious to investigate the strange creatures. She was only a dozen feet from the shore when the mermaids began their opera.

The clamor struck the young sea monster with terrible force, sending her tumbling back through the water. When she regained her senses she fled as quickly as any sea monster could. In her hurry to get away she broke the surface and sent a splash sailing into the air in the direction of the assembled mermaids.

Mermaids, as I’m sure you’re aware, do not mind water, but even the most water-loving soul is bound to take issue with finding herself abruptly covered in cold ocean water and bits of seaweed at the precise moment that she has begun a very important musical performance, and their screeches followed the sea monster far across the ocean.

The disgruntled mermaids postponed their opera and spent the rest of the day discussing the sea monster they’d seen. They called the sea monster all sorts of unflattering names, working themselves into a frenzy, until one mermaid said, “It’s evil!”

The other mermaids fell silent as the words sunk in.

Evil, according to mermaid legend, was only a fantasy. Or that’s what they’d always thought, but now they weren’t so sure. If sea monsters were ill-mannered enough to interrupt a performance when it was only just beginning, who knew what other behaviour they might be capable of? When one mermaid noted the sea monster’s very large size, and its very large mouth, they began to wonder whether the monster might be impolite enough to eat mermaids for sport.

Now, by this time the sea monster had found her southern current and taken it to the warmer regions where she met her companions and told them about the mermaids’ terrible voices.

They were a great distance away from the mermaids, but sound travels faster in water than in air, and by and by the mermaids’ discussion reached the sea monsters. It was a bit garbled by this time, but the sea monsters got the gist of it, and they were very offended by all of the things that the mermaids said.

The sea monsters all thought it very strange that the mermaids feared being eaten by them. No sea monster, so far as anyone knew, had ever eaten a mermaid, and they were a little revolted by the thought—mermaids after all were neither particularly nutritious nor flavorful. After a discussion, however, they decided that they would give it a try, if they encountered any more mermaids who attacked unsuspecting sea creatures with their infernal screeching.

After several weeks had passed, and several screeching mermaids had been eaten, they were forced to admit that it seemed an effective means of getting the terrible sounds to stop.

Meanwhile the sea monsters’ conversation was reverberating back and forth around the world until it finally reached the mermaids. It, too, was a bit garbled, but the mermaids got the gist. They had thought they’d heard the worst of it when they got confirmation of the sea monsters’ dietary habits, but they were unprepared for such a very unflattering description of their voices.

When, after several days, they had recovered from the shock, they decided that if the sea monsters so feared their songs, the best way to ward them off would be to sing as loudly as possible.

Many ages passed in a similar sorry state. The mermaids sang their operas, driving many a sea monster to the point of madness, and the sea monsters reluctantly adopted a diet of mermaids. And this is probably why there are so few sea monsters and mermaids left in the world nowadays.

There are a few left still. You can find them swimming somewhere in the forgotten corners of the world, and I am told that they have at last put aside their differences. The mermaids’ musical talent has improved considerably through the long ages of practice, and the sea monsters no longer mind it so much. Indeed, I have heard that sea monsters have become fond of trumpeting, and that mermaids and sea monsters join together in great harmonies. In secluded places, if you are very lucky, you can still hear them sing.

Sometimes their songs contain stories, and sometimes the stories are about their sorrow and regret for the prosperity that they lost, and about a time long ago when mermaids and sea monsters were everywhere in the world. And if you ever meet a mermaid or a sea monster, they will tell you to be careful about the stories you tell and the stories you listen to — because once a story is told it can never be taken back.

Commentary

This was a lot of fun to do! Knowing that I was writing a story that would be read aloud seemed to have a big effect on the style of my writing, and I was much less worried about making it realistic or conforming to typical writing rules. I also found it interesting how I started thinking about the people I’d read it to and in some ways adapting it to suit their tastes long before I actually read it to them.

I didn’t think about the content too carefully as I was writing it, but looking back I made some choices that might be somewhat unique – for example using two groups of people rather than individual characters, the way “evil” is never entirely real, or delivering the ending message of the story through my characters rather than through the narrator. I’d be interested to hear people’s thoughts on the effects of this!

Works Cited

Globe, Warwick. “The Mermaid and the Dragon.” <http://www.artsycraftsy.com/goble/goble_mermaid.html>

Ellis, R. “The ‘Great Sea Serpent’ according to Hans Egede.” <http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hans_Egede_1734_sea_serpent.jpg>