I decided to answer Question #2 this week, with a focus on the Indian Act of 1876. I found this particular piece of legislation interesting because it’s had such significant effects, and because it continues to shape our government’s relationship with Indigenous communities even today. The UBC Indigenous Foundations website has a good overview of the Indian Act through history that I rely on for a lot of my information.

From the beginning, the act operated from a perspective of encouraging assimilation with the dominant culture and treated Indigenous people as children; it also limited their self-governance and gave the government many powers, like the ability to decide which people received benefits.

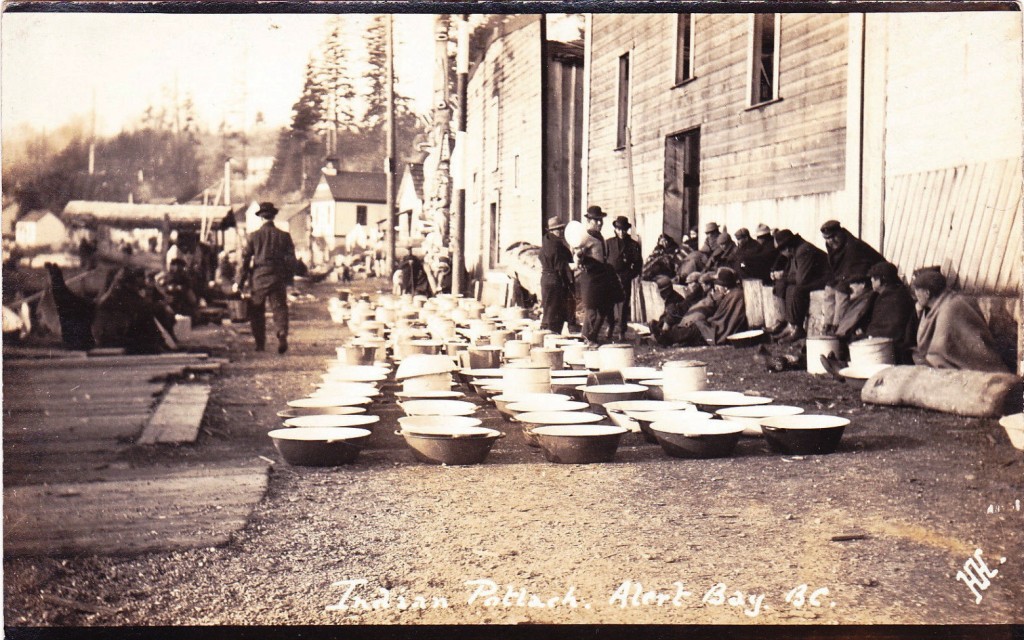

The government’s goal of assimilating the First Nations was often extremely explicit – in the 1920s, for example, the government official responsible for Indian Affairs said to Parliament, “Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian Question.” A primary reason for banning potlatches in an 1884 amendment to the Indian Act seems to have been the fact that they interfered with this assimilation.

I’ve always taken for granted that assimilation is a negative thing – along with most of my friends who talk about it – so I was surprised to find that in a 2012 National Post article entitled “Is it time to scrap the Indian act?” many of the readers who wrote in explicitly supported assimilation. Didn’t they learn anything from Star Trek?! But on a more serious note, I can’t help thinking that they would quickly change their mind if they were asked to assimilate to First Nations culture, or if Canada made French the only official language and tried to assimilate English speakers into that culture.

Another aspect that stood out for me was the way the Indian act was amended in the 1920s to prevent Indigenous people from hiring lawyers to fight for their rights. From a modern perspective, there’s something particularly immoral about an organization making arbitrary rules about certain groups of people being unable to question them in court. It’s hard for me to see this as anything other than an admission of guilt, but I’m curious about how it would have been taken at the time.

In 1951, the more oppressive sections including the ban on potlatches and hired legal counsel were removed, returning it to a state closer to the original version.

One significant part of the Indian Act was the introduction of “Indian Status,” where the government was able to decide who counted as an “Indian” person (and who, therefore, was eligible for the special rights that entails). At times, the government revoked the status of any Indigenous person who reached a certain level of education.

The Indian Status system was also responsible for widespread discrimination against women, because women who married non-Indigenous men forfeited their status (as well as the status of their children), while men who married non-Indigenous women had no such problem. In effect, this forced Western forms of discrimination – which their own culture didn’t share – onto the Indigenous population. Bill C-31 in 1985 and Bill C-3 in 2010 were intended to remove their discriminatory policies but failed to do so: as the link above notes, “Grandchildren born before September 4, 1951 who trace their Aboriginal heritage through their maternal parentage are still denied status while those who trace their heritage through their paternal counterparts are not.”

I think my research generally supports Coleman’s argument about the project of white civility. It’s hard to imagine the historical moment in which these laws were formed, but it seems like a lot of it was based in fantasies of civility – even when they were destroying Indigenous people, the government always tried to frame it as doing what’s best for them. Coleman also mentions forgetting our government’s uncivil acts of colonialism and nation-building as a necessary part of the idea of white civility, which I think is demonstrated both in the existence of “well-meaning” modern proponents of assimilation, and in the fact that so many people (myself included) have never heard of the oppressive details of the Indian Act. Harold Cardinal seemed to realize the importance of remembering when in 1969 he called the Indian Act a “lever in our hands and an embarrassment to the government, as it should be.”

Works Cited

Crey, Karrmen, and Erin Hanson. “Indian Status.” Indigenous Foundations. <http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/government-policy/the-indian-act/indian-status.html>

Hanson, Erin. “The Indian Act.” Indigenous Foundations. <http://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/home/government-policy/the-indian-act.html<

“Indian Act Background.” <http://www.usask.ca/education/fieldexperiences/tools-resources/diversity1/saskatoon-public/grade-4/3-Indian-Act-Background.pdf>

Joseph, Bob. “Indian Act and Women’s Status Discrimination via Bill C31 and Bill C3.” Ictinc.ca. <http://www.ictinc.ca/indian-act-and-women%27s-status-discrimination-via-bill-c-31-bill-c-3>

Russell, Paul. “Today’s letters: Is it time to scrap the Indian Act?” National Post. <http://news.nationalpost.com/full-comment/letters/todays-letters-is-it-time-to-scrap-the-indian-act>