Question #2: In this lesson I say that our capacity for understanding or making meaningfulness from the first stories is seriously limited for numerous reasons and I briefly offer two reasons why this is so. […] In Wickwire’s introduction to Living Stories, find a third reason why, according to Robinson, our abilities to make meaning from first stories and encounters is so seriously limited.

In this week’s lesson, Dr. Paterson points to two primary obstacles to finding meaning in early stories. The first is the way in which the social process of telling stories is disconnected from the story, and Wickwire provides some specific examples of this disconnection—she says that when listening to Robinson’s story, she was “hooked on what felt like a direct encounter with coyote—a living coyote linked to Harry by generations of storytellers” at that, by contrast, printed versions are short and lifeless (8). Wickwire also mentions that the identities of individual storytellers and details that are specific to local communities are often erased when composite stories are created, and stories with contemporary political content were often ignored or edited by the anthropologists who recorded them.

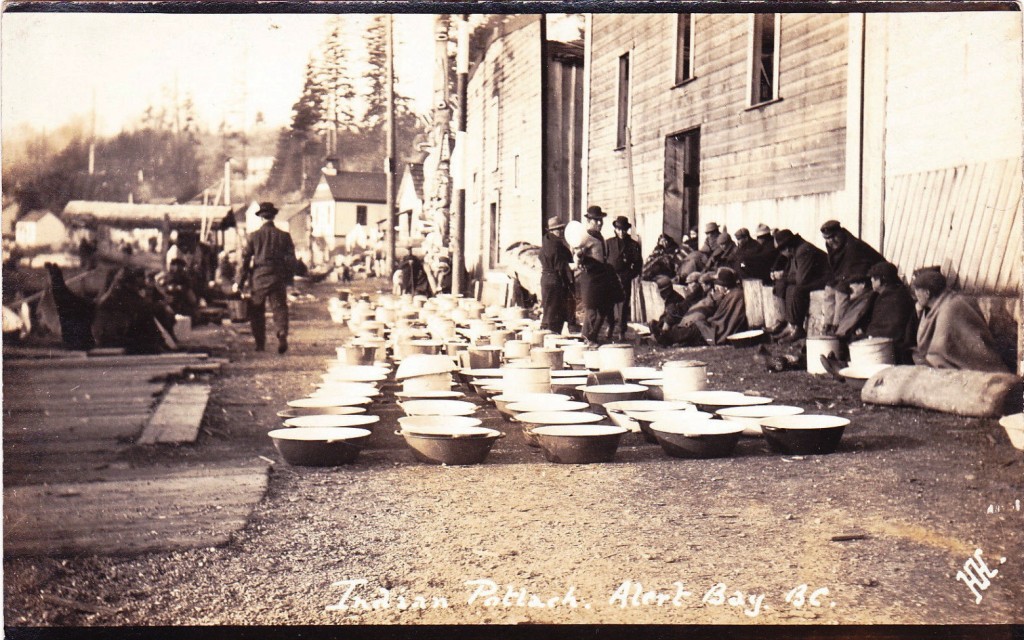

The second is the way storytelling among Indigenous people was prohibited, and the way children were removed from their culture and their stories when they were sent to residential schools. I was actually quite surprised to learn that potlatches were officially banned from 1880 to 1951, and I thought the link provided in the lesson gave a fascinating overview of the history. The suggestion that it was partly because potlatches were seen as a “detriment to the expansion of the nation’s economy” stood out for me, because it really emphasizes that they were being targeted because they weren’t “useful” enough to our Western capitalist culture. The fact that stories were targeted also points to the great importance and power of storytelling.

Which brings me to the third reason, expressed by Harry Robinson in Wickwire’s introduction. The third reason, I think, can be summed up as the difficulty of understanding meaning in cultural contexts and traditions that are so different from our own, and in particular with settlers’ inability or unwillingness to adopt new frameworks and ways of thinking.

Robinson’s story about Coyote and the two twins seems to be all about these failures of communication and understanding, as the younger, white twin steals a piece of paper and refuses to share its contents with the older twin. I found it interesting that Coyote travels to the King of England to work out some codes about how Indigenous and white people would live and interact, which resulted in the creation of a “Black and White” book, and that Harry’s friend Edward Bent tries to read it. These details show that Indigenous characters attempt, out of the willingness or necessity, to work within the cultural framework of the settlers, even if the attempt is ultimately unsuccessful and wrapped up in the violence of residential schools—and this, in turn, draws attention to the fact that there’s no reciprocal attempt on the part of the settlers.

Wickwire says that the same story explains how Indigenous and white people derive their power from two completely different sources, with Indigenous people’s power in their “hearts and heads” and white people’s power “on paper,” which also emphasizes differences in culture and language. And when Robinson says that this story was the thing that was missing from the political meetings of his youth, I think he was drawing attention to the settlers’ failure to consider these issues from any perspective but their own.

Robinson also talks a lot about the importance of taking sufficient time to hear these stories, telling Wickwire that “It takes a long time. I can’t tell stories in a little while” (12). Later, he tells her to

[…] think and look

And try and look around at the stories.

Then you can see the difference between the white and the Indian.

But if I tell you, you may not understand.

I try to tell you many times

But I know you didn’t got ‘em…

So hear these stories of the old times.

And think about it.

See what you can find something from that story… (18)

And on the next page:

See if you can see something more about it.

Kind of plain,

But it’s pretty hard to tell you for you to know right now.

Takes time.

Then you will see. (19)

So we need to hear many stories rather than just a few. (Notably, Robinson’s largest concern with the book was that it hadn’t included all of his stories.)

We need to “look around” at the wide breadth of the stories and consider them collectively.

And we need to think about it thoroughly, repeatedly, and over a long period of time.

Robinson’s point, I believe, is that we can’t really make meaning from First Stories if we approach them from a Western context and way of thinking, which is what inevitably happens when most of us read a single story or even a collection of stories. It’s only through becoming immersed in an Indigenous context that we can start to see true meaning, and that only starts to become a possibility if we can take in a near-lifetime of stories and learning.

Works Cited

“Alert Bay, potlatch, 1910s.” Flickr. <https://www.flickr.com/photos/benbradley/16959540456/>

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 2:2.” ENGL 470A Canadian Studies. <https://blogs.ubc.ca/courseblogsis_ubc_engl_470a_99c_2014wc_44216-sis_ubc_engl_470a_99c_2014wc_44216_2517104_1/unit-2/lesson-2-2/>

“The Potlatch.” The Story of the Masks. < http://www.umista.org/masks_story/en/ht/potlatch02.html>

Robinson, Harry. Living By Stories.

I think you really hit the nail on the head at the end; only with “a near-lifetime of stories and learning” can we hope “to see [the] true meaning” of First Stories. I like that because it both illustrates the necessary depth for understanding and juxtaposes the immersion of Indigenous peoples into Western culture.

While immersion certainly seems necessary in order for understanding to cultivate, do you think that only after a near-lifetime of stories and learning we can hope to gain “true meaning” from First Stories? This question reflects more on this definition of truth. While I think there is certainly truth in one single story, I understand that there is danger in it as well due to a lack of perspective and understanding. However, I don’t think that means because one story is “single-sided” — as Adiche puts it — it no longer holds any truth for its reader. What I’m asking is:

Pulled out and put on its own, do you still agree with your last sentence and, if you do, does that mean anything less than a near-lifetime of stories and learning does not result in true understanding?

(Great post and I’m really interested in hearing your thoughts)

That’s an interesting question. I used the worth “true” without thinking about it all that much, and I suppose the answer really does depend on how you define “true meaning” – there are some who would say there isn’t a single true meaning in stories at all.

I think it’s also a lot more complicated than a binary of either understanding the meaning or not. I’m sure there are a lot of stories that we can understand and get some “truth” out of on a superficial level, but that we’d be able to more fully understand and really feel them if we were coming from the right context.

🙂

A great answer to my question – thank you 🙂

Thanks! 🙂

I found this to be an excellent summation of the challenges of interpretation.

Adam Robinson’s storytelling seems to encapsulate the challenges of finding meaning in Aboriginal storytelling as an outsider – his English is challenging and his style indifferent to Western norms; and, perhaps for those reasons, there is a clear sense of underlying passion and animation to it. The writing has a voice that seems to jump from the page into one’s ears.

It may be that the attempt to *find* meaning in it is precisely the problem. To me, Robinson’s starting point is the need to be in company. The first requirement is familiarity with the storyteller and with the world in which his stories are set. Only then, with the establishment of a shared context, can meaning approach.

Great read!

~Mattias

That’s an interesting point, about how trying to find meaning may be part of the problem – I hadn’t considered that before. I was definitely very fixated on meaning when writing this, just because of the wording of the question I was answering.

🙂

An excellent blog post! I really wonder: what does it take to truly understand another person who is from another place, with different stories? Is it even possible? What if instead of interacting with stories, we learn to interact with their tropes instead? Simple concepts. Building blocks.

In regards to Indigenous stories, I think lots of their “tropes” and elements (note that I’m simplifying here, using a western concept like “tropes”) have much to do with the land and nature they lived in for generations. Characters like Coyote and Raven, for example, have been mentioned across many of our past readings.

I think what western readers may fail to contextualize are these nature-and-place elements. As an outsider, I cannot really relate to coyotes and ravens. I know vaguely what kind of animal they are, but I don’t interact with them on a daily basis, as Indigenous peoples probably did for generations. That’s why, when Coyote and Raven appear in in their stories, they automatically contextualize them in their everyday living world.

Westerners do the same thing. We know what a lamp is, for example; we use lamps every day. Therefore, when we read about a lamp, or see a lamp in the opening credits of a Pixar film jumping up and down, we automatically contextualize it into our worldview and we *get* it. When I see a jumping lamp, I see the humour and the quirk because lamps are not supposed to jump. Yet someone who has only used candles all their life may find that not strange at all—to them, the lamp could be animated creature.

– Charmaine

Thanks for your comment! Really good points. I think that tropes and stories are probably pretty connected.

There are probably a fair number of settlers who (to use your example) do interact with ravens or coyotes on a daily basis – especially in the past, or if they live in certain areas – so I wonder how that fits in. Do they understand First Stories significantly more than the rest of us? Is there still something missing from their understanding?

🙂

Hi Cecily,

What do you make of the concept that while the Western settlers make little-to-no attempt to incorporate an Aboriginal viewpoint, in Robinson’s story, the Coyote adapts so effortlessly adapts to theirs by writing the book? My feeling, based on the limited readings I’ve done in this course so far, is that there is an assumed sense of superiority engrained into the Western conception of First Nations – while it probably started with whoever declared them savages, even some modern postcolonial critics sometimes give me the impression that Aboriginal traditions are curios to be preserved instead of genuine alternatives to Western thought. It seems like one would require full immersion within the culture and traditions in order to overcome these assumptions, but if these assumptions are what hold us back in the first place… It’s hard to see a clear path to a solution.

🙂

Very interesting! If as you say, that we need to read a wide breadth of stories, then can we every really know anything? Couldn’t the next story just change the meaning of every story before? I agree that you can’t know a culture through one story, but can you ever completely understand a culture unless you were raised in it? Heck I still make cultural mistakes. I guess my question to you would be, how many is enough?

🙂

Hi Cecily,

I really enjoyed reading this. A lot of other people are questioning whether one can truly understand a different culture/society even after having studied it and its ‘stories.’ Would you equate what you and Robinson are saying with cultural relativism?

As for your last paragraph, do you think it is worth devoting a lifetime to reading and learning just to understand a culture and people not of your own to truly get them? That’s a whole lot of time and energy. For me, I don’t think it’s even possible to truly understand my own culture and people if I spent a lifetime trying to. There’s so many nuances, intricacies, and contradictions in specifics that it would take more than just a lifetime. I’m sure you already know, but if you look into different disciplines, for example, you’ll find so many contradictions. From sciences to social sciences and humanities there are tons. To this day we have people trying to figure out what the fruit was Adam and Eve ate in the Garden of Eden, how certain drugs (like Tylenol) we consume actually work, etc etc. Then you get to specifics and we have people arguing about definitions, methodology, etc. Many have devoted a lifetime’s work on a specific topic and have come short to finding an answer/solution (that’s not to say they’ve failed because I’m sure many have furthered knowledge). In any case, what I’m trying to get at is it’s exhausting. I think hearing too many stories can really take a toll on someone. Thoughts?

🙂