When working my way through this week’s podcasts and readings and the influence of risk based algorithms I was reminded of my previous career as an immigration officer with the Canadian government. Approving visitor visa applications (tourist, business, workers and students) is a risk management process. When reviewing applications immigration officers are trying to determine what the likelihood is that the individual applying will overstay their visa, work illegally or make a bogus refugee application after entering Canada. If it is determined that there is a reasonable likelihood that they may fail to leave at the end of their visa’s duration their application is refused. Determinations are made on scant documentary evidence, officer intuition and a good deal of undocumented (i.e., never included in the officer’s official notes) guidance and advice shared among officers.

It is an arbitrary and flawed system, highly subjective and inconsistent. The people making the decisions are for the most part foreigners living in a part of the world where they may have little or no local knowledge or cultural understanding. The workload, in places like, for example, China or India, is enormous and unrelenting. Consider for example that pre-Covid Canada was receiving approximately 30,000 student visa applications a year from individuals in mainland China. That means an individual immigration officer is making determinations on thousands of applications every year.

It is, therefore, not hard to see why the Canadian government would be interested in using AI technology to remove some of the decision making responsibility from human officers, as they began doing in 2014 (CBC Radio, 2018). Regrettably, the approach taken by the Canadian government at that time does appear to be a good example of the 3 factors associated with ‘bad’ algorithms highlighted by Dr. Cathy O’Neil in her interview on the 99 Percent Invisible podcast. The algorithm used was widespread, potentially influencing hundreds of thousands of immigration decisions, decisions that can have huge consequences for the individuals applying; the process was secretive for a number of years; and destructive, disproportionately disadvantaging certain groups (put simply, wealthy individuals have much less trouble obtaining visas to Canada). It should be noted that the Canadian government has recently established what it calls an ‘algorithmic assessment tool’ which is in part an attempt to address the type of criticism put forward by advocates such as Dr. O’Neil.

However, I think there are additional concerns when it comes to deploying AI in areas like immigration, beyond those outlined by Dr. O’Neil. For example, it could be assumed that the algorithms would be built using very problematic data. As I alluded to earlier, many of the factors that have historically gone into an immigration officer’s decision making process are left out of the official record. What is left out is usually the very obvious biases that the officer or groups officers in a particular office have built up over time. The algorithm would bring consistency and efficiency, but it would also replicate and perhaps amplify many of the biases inherent in the traditional system.

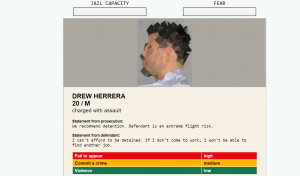

Pocaro, in his article regarding ‘Detain/Release: simulating algorithmic assessments at pretrial’, states that: “Software has framing power: the mere presence of a risk assessment tool can reframe a judge’s decision-making process and induce new biases, regardless of the tool’s quality.”(2019) I can easily imagine this playing out in a similar fashion among immigration officers. There are usually no official guidelines as to how many applications an officer should approve or refuse, but informally there is feedback provided by managers and co-workers. Overtime officers generally fall in line. The AI risk assessment tool would increase the level of conformity and leave less room to question the status quo.

The immigration algorithm and those like it are presented as solutions to complex problems, assuming that what is needed is greater efficiency and consistency. However, the answer to complex problems, like for example how to equitably and transparently manage immigration into Canada is not solved by simply providing greater efficiency and consistency based on flawed data.

References

CBC Radio (2018, November 16). How artificial intelligence could change Canada’s immigration and refugee system. The Sunday Magazine. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/sunday/november-18-2018-the-sunday-edition-1.4907270/how-artificial-intelligence-could-change-canada-s-immigration-and-refugee-system-1.4908587

Nalbandian, L. (2021, April 28). Canada should be transparent in how it uses AI to screen immigrants. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/canada-should-be-transparent-in-how-it-uses-ai-to-screen-immigrants-157841

Pocaro, K. (2019, January 8). Detain/Release: simulating algorithmic assessments at pretrial. Medium. https://medium.com/berkman-klein-center/detain-release-simulating-algorithmic-risk-assessments-at-pretrial-375270657819

Vogt, P. J., & Goldman, A. (Hosts). (2019, May 12). The Age of the Algorithm (No. 274) In Reply all. Gimlet. https://gimletmedia.com/shows/reply-all/brho4v/274-the-age-of-the-algorithm