Introduction

In the first four weeks of ETEC 540: Text Technologies, we delved into the concepts of the evolution of language and text with its impact on culture and society in the framework of technology. Text is a technology that has had far reaching impacts on societies since its inception. In the last eight weeks of the course, we’ve considered how digital technologies have mapped onto literacy and what direction it will point users in and the impacts it will have. People are generally understanding of framing the digital world as ‘technology’ however most people are less familiar with the idea of historic literacy disruptions as technological change perhaps with the exception of course, of the Gutenberg press. Technology is not just about machinery, but as Westers defines it “the application of scientific knowledge to the practical aims of human life” (Britannica, 2018). Therefore, I have chosen to focus my final task, Describing Communication Technologies on a historical text technology disruption in the form of a system of writing implemented in 15th century Korea now called Hangul. This paper considers the reaction to and impact of a technology that unlocked information and expression formerly unavailable the majority of a population. This brief historical framework is intended to be a reflective aid to consider the future impact of current disruptions in literacy, communication and knowledge access that are happening so quickly today. As today’s change is unprecedented it helps to have a historical framework, because as they say history does not repeat but it does rhyme.

Historic timeline

In what is modern day both (North and South) Koreas, a system of writing known in Korean as Hanja (Chinese characters) was brought to Korea from China and mapped onto the existing language. “Hanja became prominent in use by the elite class between the 3rd and 4th centuries”. (Hanja, 2022). It is worth making mention for the unacquainted reader that in old Asia, China and therefore Chinese writing was at the centre of high culture and higher learning. Similar to the way Greece and Latin would be to old Europe. Most surrounding countries have some influence of Chinese characters. In the case of Korea, Vietnam, and Japan, it was imported and mapped on top of their existing and unrelated languages. “The Han enjoyed a cultural and literary monopoly in Asia for many centuries. When writing began to spread to other Asian peoples, they first wrote in Chinese” (Gnanadesikan 2008, p.77). It useful to note that “the distributions of language structures that people are exposed to in print are different from those that people encounter in speech”. (Stanovich & Cunningham, 1992), one can imagine the difficulties encountered in having a foreign script mapped onto an existing language. Unlike a modern developed society, most people did not enjoy the luxury of time to study Chinese characters. Hanja was primarily used by the small elite class in Korea who were literate.

It was the King of Korea, the Great King Sejong in the 15th century who set out to solve this problem by commissioning scholars to come up with a new text technology that would enable the masses to be empowered through literacy in their own language and home country. He is quoted in saying, “since we lack this writing system of our own, even if there are people who have things to say, there are many who cannot express it in writing and thereby cannot flourish” (Gottlieb 2021 p.80)

Besides the advantages of having a language designed specific to the language and culture it represents, as text technology, Hangul has been described as the most scientific and successful text with its origins well documented. “Those who trumpet the wonders of the Greek alphabet are misguided; it is the Korean alphabet which is the true paragon of scripts.” (Gnanadesikan (2008 p.191)

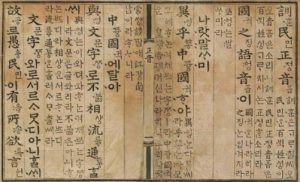

In its original inception king Sejong implemented the Hangul first as an add-on to the Hanja to open up accessibility to the masses of illiterate population.

Fig 1. Both Hanja and Hangul scripts used together. (Hunmin Jeongeum, 2015)

Fig 2. Hangul used exclusively. (Asia Society, 2023)

- Resistance to change.

When the King Sejong introduced the Hangul, the system of writing that he created, pushback from his closest and highest literati class was immediate. The guise of the opposition was that it would offend China who claimed suzerainty over Korea. That China was high culture and “only barbarians used scripts other than Chinese”. Gnanadesikan (2008) p.203. Most likely the real opposition was the threat that the literati class would lose control over regulating culture, information, and social order by lowering the barrier to literacy. This is a reoccurring theme throughout history when we see disruptive technological change that redistributes power in the form of knowledge. I hope the reader will see the relevance here no matter their political bent as to the technological disruption today making knowledge more accessible to more people and societies’ various reactions to it. It was not long ago that western societies were very clear about the importance of freedom of speech and expression and now we see that being challenged.

- implications this development had for literacy and education.

The introduction of Hangul did not create an immediate economic, scientific enlightenment, literacy miracle but it laid a technological foundation to open literacy to the masses. Available to the masses, Hangul was used by the common people, helping to shape a new national identity and pride.

However, during the Japanese occupation of Korea from 1910 to 1945 Hangul was outlawed and Japanese was the language and text enforced. Hangul survived underground and upon liberation, all Koreans had a newfound pride in their language. Gnanadesikan notes that at the end of World War two and subsequently Japanese occupation, the illiteracy rate in Korean was 78 percent. With the resurgence of Hangul, and great efforts to educate the masses illiteracy was essentially eradicated in North Korea by 1949 and not long after that in South Korea. Keep in mind that in 1949 both Koreas were by any measure astonishingly poor nations. “The population of literate people went from 22% to 98%.” (Education in South Korea, 2023). “Korean children can read before they begin their formal education”. Gnanadesikan (2008) p.203.

South Korea, when the opportune time came was able to draw on a dedicated, hardworking, literate work force to climb the value-added manufacturing chain. It can be argued that Hangul was one of the tools that allowed it to claw its way out of poverty and reign in an economic miracle. The hangul text technology allowed literacy not to be a barrier.

In North Korea, which is a very impoverished society also does have an extremely high literacy rate of supposedly 100%. North Korea is an example of an even more extreme reaction to colonization in which they banned all foreign words and text from their language. Hangul is also one of the tools North Korea uses to educate their population, while we don’t see this as an example of good education, they are undeniably competent.

Literacy and text go beyond unlocking access to economic wealth. A literate nation has more potential to express their feelings, share music, stories, love, ideas and disperse it immortally in text. A nation having its own form of writing can create a sense of national pride and belonging. Over time even the text itself can elicit emotion. In a study of emotional responses to Hangul text “experts extracted 75 emotion adjectives derived from 300 Korean fonts” (Kim & Lim, 2018)

Fig. 3. Psychology derived from Hangul typography based on several blogs of font providers. (Kim & Lim, 2018)

What lessons can be garnered from this historical perspective that can be apply to current technological change?

The two neighbouring Koreas provide for a perfect control group not found anywhere else in the modern world. Here we have two very literate nations that at the same time adopted this text technology. For our purpose the control is the shared history of the implementation of the text technology. The two societies diverged wildly after World War two. The North is a poor, autocratic communist nation run by a dynastic military cult allowing no freedom outside its circle of power. While not wealthy per capita, is advanced in arms manufacturing and punches way above its weight in global politics. It’s system of nationalism through effective propaganda (to a literate population) is second to none. The South by contrast, a republic, transformed into a hyper capitalist, democracy that through an economic miracle became one of the wealthiest, well-educated, well-travelled, high-tech nations in the world.

One may deduce from this that having a technology that allows the population to become literate is no guarantee of economic wealth or freedom. That is not to negate the power of literacy it only highlights that it is a means not an end. Technology amplifies human behavior for better or for worse. This maps on perfectly to the notion brought forward by Dr. Shannon Vallor in a presentation (Lessons from the AI Mirror Shannon Vallor, 2018) on AI that the trajectory, outcome, or ethos of AI is not mysterious, it is in fact a mirror to human behaviour and moreover acts as an accelerant on that behaviour.

There are several technological revolutions happening now affecting communication, literacy, education, and dispersion of knowledge. Social media has allowed unprecedented aggregate human connection and immediate flow of information. The mass consumption of unlimited audio and video with the cost of production and distribution effectively dropping to zero allows for masses of content producers. These just to name a few, all allowing potentially greater access to knowledge and types of literacy. Algorithms and AI can be used to steer the direction of these tools. It accelerates the potential to control or the potential to democratize information.

Modern change seems to be happening at a dizzying pace. However, “our ancestors at times were just as bewildered by rapid upheavals in what we now call “networks”–the physical links that bind any society together” (Wheeler, 2019). In the same way that the literati resisted relinquishing control to the illiterate masses through controlling distribution of information in the past, modern attempts at control of new technologies are taking place. The consequences of freedom are great as are the consequences of control. We can observe in real time today societies, some open and free, others censored and controlled using the same types of technological tools. We don’t know what the outcomes will be.

Conclusion.

Historical milestones in text and communicative technology such as the introduction of Hangul are relevant to the change in technology we are witnessing now. We are moving through powerful technological change in communication and access to information. We are witnessing real time both marvelous and mischievous effects. Technologies may change, but they remain tools. They will bring communication, literacy, and information, which is power. As Dr. Vallor points out, (Lessons from the AI Mirror Shannon Vallor, 2018) this power accelerates the mirror image of our nature. That is to say, we need to understand ourselves in the past, to help us navigate thoughtfully into the future through technological disruption that will change life as we know it, because our nature changes much slower than technology. Having examples of the historical impacts of text technologies impacting communication in context can serve as a tool to make predictions about the future of new communication technologies on literacies and the spread of culture. The impact on education is that new literacies of being discerningly cautious while embracing digital change.

References

Asia Society . (2023). Korean Script. https://asiasociety.org/education/korean-language

Britannica. (2018). technology | Definition & Examples. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/technology

Gottlieb, B. (2021). Hangul as an Edge Case of the Alphabet Effect Or King Sejong’s Proto-Modernist Dilemma. China Media Research, 17(3), 72. 7 Source: 최현배, “외솔 최현배 박사 고희 기념 논문집” (1968), 27-28 쪽 참조.

Gnanadesikan, A. E. (2008a). Chinese: A Love of Paperwork. 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444304671.ch4

Gnanadesikan, A. E. (2008b). King Sejong’s One‐Man Renaissance. 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444304671.ch11

Hanja. (2022, November 23). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanja#:~:text=Hanja%20became%20prominent%20in%20use

Hunmin jeongeum. (2015). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E8%A8%93%E6%B0%91%E6%AD%A3%E9%9F%B3.jpg

Kim, H.-Y., & Lim, S.-B. (2018). Emotion-based Hangul font recommendation system using crowdsourcing. Cognitive Systems Research, 47, 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2017.10.004

Lessons from the AI Mirror Shannon Vallor. (2018, November 6). Www.youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=40UbpSoYN4k

Stanovich, K. E., & Cunningham, A. E. (1992). Studying the consequences of literacy within a literate society: The cognitive correlates of print exposure. Memory & Cognition, 20(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03208254

Wheeler, T. (2019). From Gutenberg to Google : The history of our future. The Brookings Institution.

Wikipedia Contributors. (2019, April 10). Education in South Korea. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_in_South_Korea