Due Friday March 28 by 4pm, this comment must incorporate self-reflexivity (see ‘practising reflexivity, or revisit the first reading we did)

Due Friday March 28 by 4pm, this comment must incorporate self-reflexivity (see ‘practising reflexivity, or revisit the first reading we did)

Reading Isabella Hammad’s “Recognizing the Stranger,” I kept coming back to ideas of recognition and how turning points shape stories. Hammad talks powerfully about “recognition,” meaning the moment we suddenly see hidden truths in our own or collective narratives. This connected deeply with the peacebuilding ideas from Hawksley and Mitchell, especially their view that true peace must include justice and acknowledging suffering.

The current student strike for Palestine (which I’m glad happened, having voted for it) provided a meaningful context for my reading, aligning with Hammad’s observations on selective humanism and how international reactions to suffering often differ unfairly. It really highlighted for me how the stories we tell shape our understanding of conflicts and humanity. Like Hammad, I’ve noticed how solidarity movements (like this strike) can dramatically shift public awareness. For me, the strike represents a powerful collective recognition, finally happening after nearly two years, highlighting injustices often ignored or minimized by mainstream media.

Hammad’s idea of a “turning point,” something we only fully understand looking back, struck me as relevant to the strike’s potential impact. The increasing solidarity on campuses, particularly here at UBC, might be seen later as a crucial shift in how the public views the Palestinian cause. Still, I wonder if this momentum will genuinely lead to the kind of “just peace” Hawksley and Mitchell describe, or if it will fade into another missed opportunity.

On a personal level, the strike has challenged me to think more deeply about my own role and complicity (even unintentionally) in these issues. It has heightened my sense of urgency in confronting biases in the narratives around me, whether educational, political, or cultural. Both texts made me reconsider how recognizing the “other” through art, literature, or activism like strikes can genuinely help build peace.

So, a question that comes up for me is: How can we actively use this idea of narrative recognition, as explored by Hammad and evident in the strike, to build more empathy and inspire real political change?

While reading the assigned readings, I gained a new understanding of historical trauma and the trauma that occurs in the present. When scholars, the international community, and governments talk to survivors about the past, it inevitably triggers their post-traumatic stress, such as painful memories of what they experienced at that time. This, therefore, leads to a discussion on how to talk about history without revictimizing the survivors.Bitek’s article analyzes the different roles of readers and writers in terms of traumatizing the people after the civil war that took place in Uganda in 1986. For me as a reader, I quite agree with the idea that we need to bear the burden of this heavy memory rather than forgetting the history.

However, the current conflict between Israel and Palestine is what we are witnessing, and I realized the importance of recognition. Recognition can be categorized in many ways, such as the recognition that Israel is engaging in military actions that are not humanitarian, and the recognition that the people of Palestine are suffering from war. It is true that this awareness makes us realize the significance of the measures that the international community needs to take, because in theory international support can help the lives of Palestinian victims. In practice, however, Israel has cut off the Palestinians from the outside world, such as the electricity system and access to international assistance. That had caused the population to suffer psychological and physical damage that went beyond the effects of the war. Moreover, international attitudes towards war are now extremely inconsistent, and the investment in war has undoubtedly exacerbated the harm to the Palestinian, which has triggered alternative recognitions, which is to take action, such as the student protest action at UBC. So, as one of the witnesses to the war, although our actions are small, I believe that one small step can drive a huge change, and that’s what anyone who opposes the war needs to get involved in.

Can one little step make a difference? What would it take to make this more meaningful?

Juli’s Rooster Woman made me think about how fiction has the power to center truth. Juli explained that when writing nonfiction, you have to be precise with dates and details you may not always recall with ‘certainty’, while fiction allows for a different kind of truth, one that doesn’t have to stick to strict timelines. This helped me understand how creative fiction can reveal deeper realities beyond linearity and rigid ways of telling ‘stories’, much like folklore has been able to do.

The Western approach to history insists on fixed timelines and official records, but personal and collective memory challenge this way of framing history. The way we remember, the way we recount-and make sense of certain things don’t always align with dominant historical frameworks, yet they hold truths and power.

Motaz’s survival and experience have also been weighing on me, especially in light of the recent killing of two Palestinian journalists. What does it mean to survive genocide while it is still unfolding? Motaz constantly talks about survivor’s guilt, about the unbearable weight of witnessing while others don’t make it through, and what it has been like for him to bear witness from afar and no longer as a journalist on the ground. He speaks about surviving but not feeling alive, which speaks to the ways trauma and the act of surviving haunt him.

Regarding how trauma is felt in the body, this quote “Sometimes my then husband would wake me up, telling me that I’d been crying in my sleep,” as well as Erin’s point about having a pit in your stomach, resonates. I’ve had gastritis for over a year, and it flares up with stress, sadness, anguish, and anxiety. Our stomach, our so-called second brain, as my gastro puts it, reacts to what we cannot fully process. When we cannot verbalize or express, our bodies react, and rightfully so.

Hammad says, “The Palestinian struggle has gone on so long now that it is easy to feel disillusioned with the scene of recognition as a site of radical change, or indeed as a turning point at all” – and I couldn’t agree more. These past months, we’ve borne witness to one horror after another. Just this week, two Palestinian journalists were killed. Mahmoud Khalil was illegally detained, and yesterday, Turkish PhD student Rumeysa Ozturk was also illegally detained by ICE while simply heading to dinner in Massachusetts. We are watching fascism tighten its grip, watching a legitimate genocide unfold, and at times, words feel entirely unable to grasp what we are witnessing.

This week, we also bore witness to starkly contradictory realities. Both Gal Gadot and Hamdan Ballal were present at the Oscars. Yet Ballal was detained and beaten by Israeli forces while Gadot was celebrated with a Hollywood Walk of Fame star, even as her latest performance was ranked among her worst on IMDb.

How do we navigate relationships with those who choose to remain apolitical in times of injustice? How can we challenge people in our spaces who shift blame onto the oppressed instead of confronting the systems of power that create and sustain that oppression?

As graduation nears, I’ve been thinking alot about how I want to exist in the world. What kind of work do I want to do? What kind of work am I willing to do? Where do I want live? What kind of community do I want to build?

Because I have moved around so much, I’ve often treated the various phases of my life as different and distinct chapters. Each chapter has been defined and disjointed by a different place, different goals, different community, rather than related parts that together form my longer life as a whole. It’s been easy to detach, self-isolate, and see friendships and community as fleeting. It’s also been easy to distance myself, be ignorant to, or in denial of, local histories and ongoing issues in the communities I’ve lived in.

Hammad talks about denial being baked into a kind of knowing, “a willful turning from devastating knowledge, perhaps out of fear” and I have to admit, this really resonated with my experiences. Everytime life has started to feel too overwhelming, I’ve picked up, moved across the world, and started anew in hopes of feeling some sense of relief. Only in retrospect am I able to recognize my moves as fear-driven decisions.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to realize this approach to life is not sustainable. While the initial excitement of being in a new place has offered temporary relief, my attempts to run away from the ever-growing, ever-present pit in my stomach, as Erin described it, is not a solution. Maybe its because I’m getting older, because I’ve found a therapist I really like, because I’m re-engaged in these class discussions about systemic violence, injustice, and hope, or because war and genocide is being livestreamed, but this chapter in Vancouver has somehow felt different from previous ones. I’ve come to terms with the fact that I can’t outrun, push down, or ignore both the individual and collective pain.

And I think that deciding how I choose to witness, and bear witness, to the global crises happening around us, as well as to parts of my own self, is critical to accepting and learning to live with it all.

I’ve often tried to quell the pit in my stomach (or make sense of injustices) by finding purpose in the work that I do and I realize now this has often been motivated by what I’ve witnessed. I decided to go to graduate school because I wanted my work to feel more purposeful or impactful, and I thought journalism would enable me to be more creative with storytelling. But over the past two years, false ideals of objectivity, the importance of “fact checking,” simplifying complexity, and the importance of linear narratives has been drilled into my practice. I understand the importance of journalism, and know that it serves an important democratic function, but I’ve also realized how rigid, extractive, insensitive, and surface-level it can be, depending on who is doing it and how it is being done.

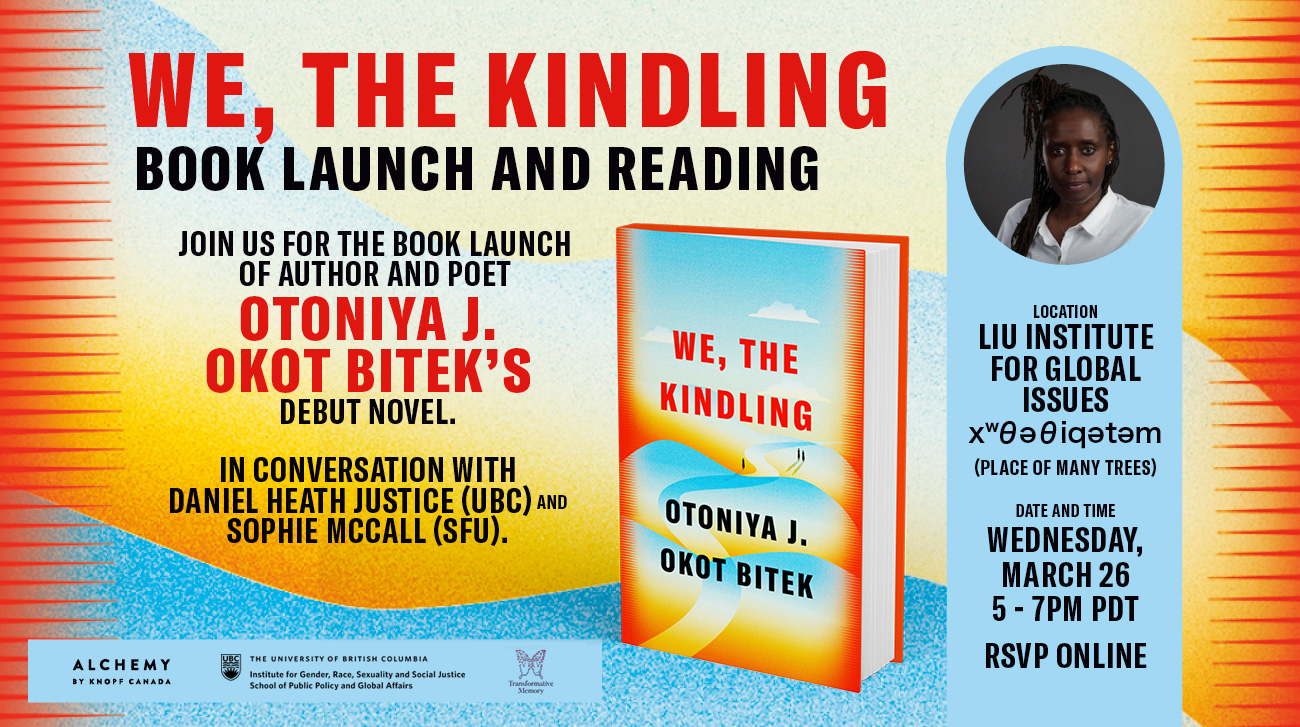

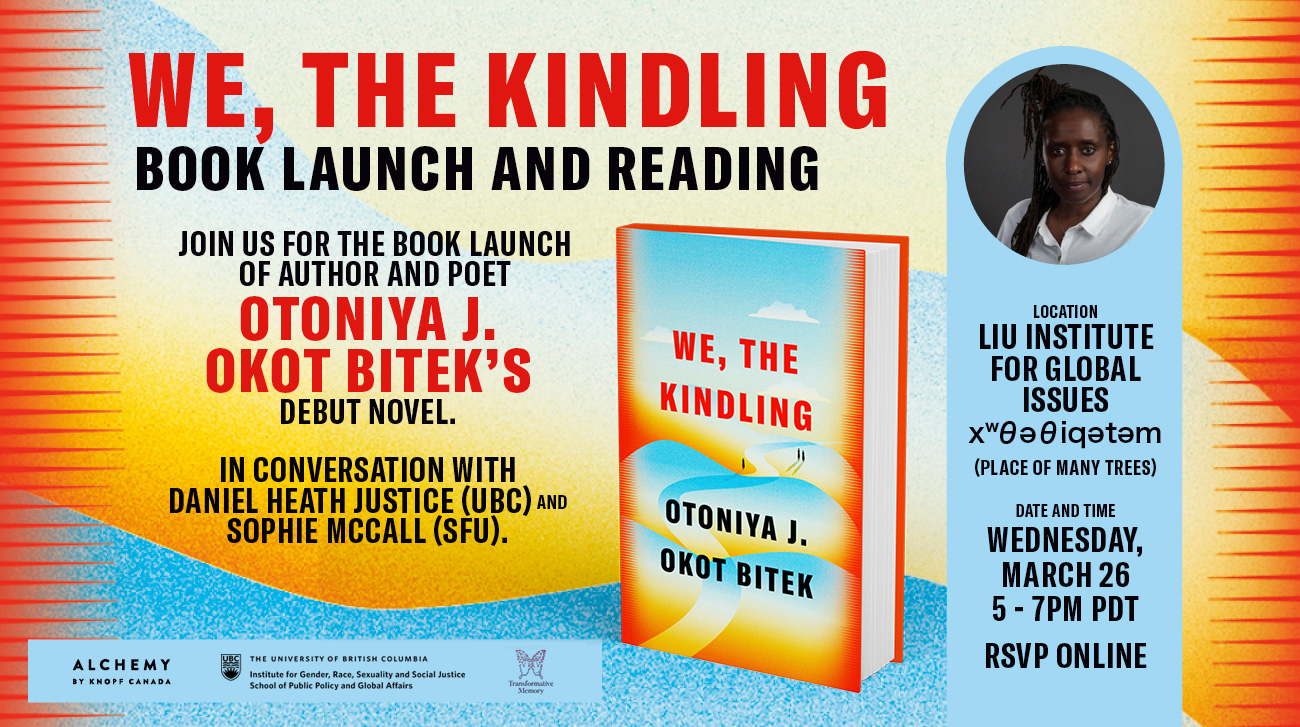

In her chapter What Choice Between Nightmares, Julie talks about her responsibility as a writer to balance the respect she has for experiences and the need to document them within “the goal of imagining and creating a future without harm” (255). This, along with her decision to turn to fiction in We, the Kindling encourages reflection on what details really matter. Through the case study of Sara’s story, Julie makes a very active and intentional decision to not repeat the “excruciating and harrowing details” and instead focuses on a retelling that reminds us that, “there is hope to be found in what we already know.”

I thought this was really beautifully captured in the passage:

“The shame is mine and it is not mine. I’m ashamed. I’m ashamed to be here. I’m ashamed. The shame is mine. The shame is not mine. Still, I’m ashamed to be here and I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m ashamed. All I know is to pick up a branch, lay it on the ground and say, I’m sorry” (257).

Anyways, I guess my questions are: How can we be more engaged in noticing the significance of each passing day? How can we be more aware of being in the midst of “turning points” as they are happening?

Hammad’s essay emphasizes the concept of “recognition,” particularly in the context of the Israel-Palestine conflict. While recognition is a familiar idea to most of us, it is difficult to practice, especially in complex situations involving violence and conflict. What I learned from the essay is that selective humanity, which is rooted in Western colonial principles, is the barrier to practice recognition. Such selective narrative dehumanizes certain groups, as seen in how Israel often justifies its oppression and killings of Palestinians. This pattern is not unique to Israel-Palestine but is also evident in many other conflicts, including in my own country, where prolonged armed conflict has been accompanied by similar dehumanizing narratives. These narratives make it easier for warring parties to engage in violence, as they reinforce hatred and frame the other side as a threat. When opposing groups continue to perceive each other this way, it becomes difficult for them to recognize one another as human beings. Without this recognition, there can be no moment of realization or transformation (or “dawn” according to Bitek) that may lead to peace.

Bitek’s story about Sara reflects the power of storytelling in narrating painful experiences and evoking an emotional connection between the teller and the listener or reader. What stands out to me in this piece is the responsibility of the listener or reader to acknowledge these difficult narratives. Stories of suffering can be hard to tell and equally hard to hear because they require emotional engagement to truly grasp their meaning or significance. But storytelling is necessary to raise awareness of ongoing injustices. As Bitek pointed out in the conversation, making people aware is important as it can lead to change. This reminds me of a class discussion last term, where a guest speaker emphasized that recognizing and acknowledging what is happening is the first and crucial step in practicing love and care—both essential for building a peaceful society.

The Rooster Woman reminds me of Evelyn Amony’s memoir, which underscores the profound and enduring trauma she experienced due to war and violence. Both stories depict the vulnerabilities of civilians when confronted by armed groups particularly due to their lack of power to resist or refuse the demands of these groups. Women and children are especially vulnerable in such conflicts. Yet, both narratives also highlight the strength and resilience of women amid these painful experiences. In Rooster Woman, what struck me most was Susannah’s perspective that “rebels were only people, just like her and just like them.” This moment of realization mirrors the instance when an Israeli soldier encountered a naked Palestinian man and recognized his shared humanity in Hammad’s essay. Bitek describes such moments as a “dawn,” a revelation that marks the beginning of change. To me, Susannah’s ability to see people beyond their roles in the conflict reveals her strength and trust in humanity, which is a crucial element of peacebuilding. Such revelations cannot occur if individuals persist in viewing others as enemies or threats—a mindset that remains deeply entrenched in conflict zones worldwide. These perspectives become even harder to shift when power and national interests are at stake. To move beyond moments of realization toward meaningful action for peace, I found Bitek’s words during Tuesday’s conversation particularly relevant: recognizing strangers and working with those who share the same passion, even if they come from different backgrounds.

Question:

Can peacebuilding efforts be sustained through individual realizations, or do they require broader structural changes?

This Monday at exactly 3 PM, I was at the bus loop at UBC, heading to the student strike. What stood out to me wasn’t just the protest itself but what happened around it. As I crossed the Nest, I noticed how the sound of chants and speeches started fading. Storm the Wall was happening right next to it with loud music, games, and energy that felt like it came from a completely different world. It was strange how quickly things shifted. Within just a few steps, I could barely hear anything from the protest. It made me think about what we’ve been discussing in class, not just silence, but how memory gets absorbed, redirected, or made to feel invisible in spaces that weren’t designed to hold it. This contrast between the protest and the campus around it reminded me of Isabella Hammad’s line: “To recognize something iS to perceive clearly what on some level you have known all along but that perhaps you did not want to know.” It wasn’t that people didn’t know the protest was happening. It’s that they could easily walk past it and not have to engage. And somehow, that felt worse than outright disagreement.

This whole moment made me reflect differently on the idea of recognition. Before, I used to think of recognition as this personal realization or maybe something that comes from really listening to a story. But being at the protest, it hit me that recognition isn’t always about hearing the truth. It’s also about whether the space around you allows that truth to stay present. In class, we’ve talked a lot about testimony and witnessing but this experience pushed me to think about it in another way. Maybe memory isn’t always silenced. Maybe it just isn’t received and that can be just as harmful.

Later, as I was reading Otoniya’s So Many Selves, one line stayed with me and brought me back to the protest: ‘The body is the one that returns. The stories are somewhere else.’ That stayed with me. A lot of people were physically there at the protest, showing up and holding space, but it felt like the deeper histories we were there to honour Nakba, exile, and everything Palestinians have endured weren’t actually present in the space. Or maybe they were but they couldn’t be felt beyond that circle. That line helped me understand that being present isn’t always enough. Testimony only becomes meaningful when there’s something or someone to carry it, receive it, and let it shift the space we’re in.

Another quote from Hammad stuck with me: “Recognition is a kind of knowing that should incur the responsibility to act for it to have any value beyond personal epiphanies.” That’s when I started wondering, what does recognition mean when the protest and everyday campus life exist side by side, with no real interruption? What happens when recognition becomes something you can walk in and out of, depending on where you stand?

That day showed me how fragile memory can be when it enters public space. It reminded me that justice is about asking what kinds of memory are allowed to stay, to be heard, and to challenge the spaces we move through. I keep thinking back to our class discussions on what it means to bear witness. I don’t think it’s only about retelling stories. It’s about making sure those stories don’t get swallowed by routine or drowned out by louder things. For me, the protest, the Nest, and everything around it became a kind of lesson: that ethical memory doesn’t just mean showing up. It means refusing to let grief or history be pushed to the side. It means recognizing what’s happening and doing something to hold that recognition in place.

In completing this week’ readings, I related to Isabella Hammad’s description of the moment of recognition, and how those moments often take place in instances of tragedy because “tragedy compresses time” (p. 10). I can still remember what that moment was like for me in the context of Palestine – of recognizing the difficult truths of the violence I was witnessing. I think it happened after I watched a video explaining the history of how Israel’s settlement in Palestine came to be. Sometimes, it honestly bothers me to think about how ignorant I was before this moment of recognition, and how much it took for me to come to that recognition.

Since then, bearing witness to the mass violence taking place in Gaza has repeatedly raised feelings of anxiety for me. I think that this anxiety stems from feeling like a useless witness at times. However, the readings this week are re-orienting me to repeated reflections I have had about taking up my responsibilities as a witness now that the recognition has taken place, instead of becoming unproductively stuck in the difficult emotions that can come with bearing witness. In ‘What Choice Between Nightmares’, Otoniya Okot Bitek says that “after the telling is done, the responsibility for the tale remains with the audience” (p. 262). This resonated with me in the context of witnessing events in Palestine. I have been told the stories, now what is my responsibility to those stories and the people who shared them?

There was so much about the responsibility of the witness in the readings, and in the Noted Scholars Talk with Otoniya, that I could relate to the student strike this week. Okot Bitek and Hammad alike acknowledge that for recognition/witnessing to have meaning or contribute to better futures, it must lead to some resulting action. I think that the strike this week was a representation of students’ understanding of this assertion by Okot Bitek and Hammad. I know that for me, the anxiety that I have described feeling has manifested into a restless pull to do what I can to make myself useful in this time. I imagine that this is a feeling many students have been experiencing. The restless anxiety, and the knowledge that simply observing the suffering of Palestinian people is not enough to responsibly bear witness, is the reason why I voted ‘yes’ for the strike and am grateful to the students who organized it.

Something that Otoniya said during the Noted Scholars Talk helped me to think a bit further about responsibly bearing witness in this time. She said that even when action takes place after witnessing, there is often still a divide between the ‘saviour’ and the ‘saved’. She pointed to the need for utilizing a conception of ‘us’, of the collective, in rationalizing the actions that we take after bearing witness. The rationale should not be just to help others, but rather, to help a collective ‘us’. This is sticking with me in thinking about how the strike is not just a movement to tangibly show solidarity with the Palestinian struggle for freedom, but also a movement to assert our expectations as students to have the institution that we live, study, and work under actually represent us and our values. Understanding actions that result from witnessing injustice as efforts to achieve better futures for the collective “us” is helping me now in thinking through my own role in bearing witness. While there can be a feeling of powerlessness at the individual level, it is important to remember that power is in the collective wherein each individual believes in a better future for ‘us’. The strike was an example of how each individual contribution – each vote, each body at the protests – can make some difference. Thus, it was great example of an attempt to bear witness responsibly in this time, which I am appreciating and learning a lot from.

Q: How do we move through the feelings of powerlessness that can take place as we bear witness to violence and injustice?

First of all, thank you so much Erin for organizing that Julie come and spend time with our class. I am so grateful to have had the opportunity to hear her speak and to have a few conversations with her. I now have another person to look up to as an academic, as a writer, and as a person. And I have another person on the list of people I would like to be taken seriously by.

Julie and I had a conversation just this morning and I was telling her I learned to read poetry from my grandma. My grandma was a very religious woman, and you could see that in the way that she wrote poetry. She didn’t write much about God, at least not in the poems I found on scrap paper amongst her things after she had passed on, but there was this quality you could tell she learned from her spiritual practice in the way she wrote passionately about the flat Alberta plains: yellow at the end of summer, blanketed in white all winter; the endless blue skies, the geese honking as they migrate away in the autumn and then back again in the spring… She had that quality with us too, where, in conversation, she could make a person feel as though they were the only person in the world for a moment.

Julie named what I was trying to express: devotion. She called it the ability to pay close and sustained attention to someone or something. I was shocked at the word – first, that it seemed to fit so well to what I was trying to describe, and second, that a word with such religious connotations felt like it fit so well into what we have been talking about this week and over the course of the entire semester. But of course Julie must know a thing or two about devotion having spent her life and her career learning what it means to be a witness.

I feel compelled to give the disclaimer that I’m not particularly religious, though I was raised Catholic, so those early experiences and ways of engaging with the world do frame a lot the way I experience and move through the world now. But these days, I am trying to figure out where spiritual knowledge fits into an otherwise secular life. I used to think spirituality was a “nice to have” but not essential and often, not even a desirable way framing of the world. I thought it closed people off to others because it centered one’s own world view, one’s own god above all others.

Today, though, I am thinking about how spiritual practice was the place I learned to sit with discomfort. I am thinking about how witnessing cannot take place unless we are able to sit with the unsettling recognition of oneself in the stranger, not just as a person, but as a person just like us. Especially when that person is the enemy. I am thinking about when we don’t recognize ourselves in the stranger and how uncomfortable that is, to sit with the knowing that there is knowing beyond ourselves, that there is humanity beyond ourselves, that there is life beyond ourselves. I am thinking about Julie’s words, “to remain human in this juncture is to remain in agony.”

Today I am thinking about how Hamad used the word epiphany, a word I have predominantly known within my faith, to mean dawn, the appearance of the enemy, and a sense of awe or God. Today I am thinking about Hamad’s criticism of the Israeli soldier’s epiphany as a centering of the non-Palestinian in order to recognize Palestinian humanity. Today I am wondering how often I have turned my gaze from the genocide in Gaza because I felt I could not bear remaining in agony. I am thinking about how many times I have looked away and then come back.

Today I am thinking about the Rooster Woman and the circular narrative in which she left and returned to herself. I am thinking about storytelling as a circular process in which there are many departures and returns. I am thinking about the reasons we leave and the reasons we come back. I am thinking about who keeps us honest, who we hold on to and who holds on to us, and who we end up being taken seriously by.

There’s not a single question mark in this whole reflection, but there are a lot of questions, I am hoping, that for this week, that’s alright.

This was my first time reading Isabella Hammad’s work in Recognizing the Stranger. When she discusses turning points, I couldn’t help but think of how October 7th marked a turning point for the entire world. It shattered the routine of our daily lives and forced us to wake up to the ongoing injustices happening around us.

I have attended over 20 Palestine protests in Calgary, Alberta, and what amazes me most is how people from all walks of life come together to stand in solidarity. I first learned about Palestine in elementary school from my Palestinian classmates and have been outspoken about it since high school. I remember attending protests in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where the crowds were predominantly Muslim and Arab. But now, it’s everyone.

In Isabella’s chapter, she weaves together stories and insights from other works, which makes me realize that I need to read more—because the more you read, the more you learn, and the more you learn, the more you grow. And the more you grow, the better equipped you are to stand up and make a difference. In the reading, she quotes:

“The flow of history always exceeds the narrative frames we impose on it. Generations continue to be born, and we experience neither total apocalypse nor a happily-ever-after with any collective meaning beyond the endings of individual lives. Yet this narrative sense remains with us, flickering like a ghost through the revisions of postmodernism: we hope for resolution, or at least we hope that retrospectively what felt like a crisis will turn out to have been a turning point.”

This resonates with me because it captures the tension between the chaotic, ongoing nature of history and our deep desire to make sense of it—to fit it into a structured narrative. But we often forget that our stories are so much bigger than us.

I also wish I had read The Rooster Women before meeting Julie. I would have better understood, in the moment, when she spoke about presenting real-life events in a linear, digestible way—because how do you explain why Twon-ne stays with the people who abducted her? And when she’s in the hospital, trying to remember her name, I thought back to our first class, when we went around in a circle sharing the stories behind our own names.

After October 7th, I started wearing a keffiyeh to work every single day until I left to start my master’s. At first, I assumed all my coworkers must know about Palestine and recognize what the scarf meant. But I quickly realized that many didn’t. I had to remind myself that not everyone grew up knowing. For a lot of people, October 7th was the first time they had even heard of Palestine. I know it can be difficult to admit when you don’t know something, so I’m sharing this link—a beginner-friendly, free resource for anyone wanting to learn or help others understand: The Palestine Academy. https://www.thepalestineacademy.com/

The thing that I’m starting to realize about reflexivity is that, in many cases, it’s less a question of whether I can arrive at some kind of answer through reflection, and more a question of whether I’m willing to admit that the answer is true. My counsellor has these two wonderful questions that continue to call me out:

What is the conversation I need to be having?

What is the thing that is true that I am pretending isn’t?

I was thinking about these questions a lot this week– I found myself thinking a lot about where I fit in as a witness and how we can think about the self in these conversations. What especially stood out to me in our conversations this week was the tension between thinking carefully through how we do the work of witnessing, while also decentring ourselves. Are these things even in tension? Perhaps not, but it feels easy to accidentally put them into tension.

Last week’s readings urged us to decentre ourselves in witnessing work, and I take that piece of advice seriously. In Hunt’s article:

“I am called to de-centre my own voice by acknowledging that my story is not the one most urgently in need of validation” (293)

Witnessing is not speaking for anyone (291)

“In my experience, it has been more powerful to make visible my inability to resolve these power differences than to pretend I can ever fully address them” (291)

“the duty of the witness is not to tell their own story, but to recall what they have experienced from their own perspective in order to validate someone else’s actions, rights, or stories” (286)

I understand that to be a witness is to be present, to be open, to be humble, and to really and truly be in the room with the person in front of you (in whatever form that may take). To be a witness is to intentionally carve out space for someone to fill, and to see the experience of another person in whatever way they invite you to. Like Julie said in her talk, this is not a book about me.

But I was also continuously struck this week by the intentionality of witnessing work, in terms of what it demands of witnesses. It’s not a passive role, where the witness is simply taking information in. In Julie’s piece “What choice between nightmares”, it’s clear how remarkably gentle the work is, and how seriously she takes the role of witnessing, of honouring the stories shared with her. She decentres herself, but doesn’t pretend like she doesn’t have a self– she recognizes her presence, role, responsibilities as an individual, without making things about her.

What I found particularly helpful about Julie’s work was the ways it offered guidance and lessons for how to go about the work of witnessing, a lot of which focuses on choosing to highlight empathetic connection versus graphic detail (258), and choosing to seek out and highlight “spaces of agency, support, and solidarity” (255). I appreciate that this brings me back to the ways I make decisions, and offers a way forward- I am doing the work of witnessing in the way I frame things, in the ways I actively take on the role of witness in the way I choose to do my work. When the “why” is difficult, I can “take refuge in the ‘how’ “ (256). I can stop spinning my tires. I can do the work, because part of me knows how to, and in some ways, it’s beautifully simple: in the decisions I make, am I centring empathetic connection? Am I centring respect? Am I choosing to highlight agency?

What is the conversation I need to be having? – Witnessing is made up of a thousand little moments where I choose to exercise agency.

What is the thing that is true that I am pretending isn’t? – I can do the work of witnessing.

In our conversation with Julie, I reflected on hubris in witnessing, and the role of the collective. Julie’s piece also offered insight here– there is a responsibility of the whole community for its stories (261). The audience needs to be receptive to the story (261). I was thinking about this quite a bit this week. Recognizing that there is community responsibility shared among many witnesses is not meant to free the individual of responsibility to witnessing. Recognizing that I am not the only witness doing the work is important because it decentres the “me” from the process, and shifts focus to people harmed and to response as a community. Being a witness is not the same as trying to be someone’s hero– which nobody asked for. Being a witness is relational, and is mindful of ego. It’s also helpful to remember that the work is shared for the sustainability of the work, and it can restore the ability that grief has to, as Daniel Heath Justice shared, function as a “connective tissue” for community.

All of this makes sense. But now that I’ve formed all of these strong opinions on witnessing, some sneaky hater tendencies are creeping up on me. I know that the whole purpose of this class has been to recognize that “the multiplicity matters” (Julie, Wednesday), and that there’s many ways to do these things. But I’ve also formed opinions on bad and harmful ways to do witnessing. And this is where the hubris is sneaking in, because now that I’m actually doing the work, I have no choice but to reckon with the Aries moon in me, and its short-fuse implications. I’m frustrated during the work. And I do think that I become a bit of a hater, which seems to be in tension with the work. But is it? At what point do the lines blur between my firm advocacy and rejecting multiplicity? Do I even have a right to these feelings? I know I can do witnessing work– but who died and made me the king of policing it? These reflections called me back to the risks of individualising witnessing in terms of how it can lead us into ego. But also, sometimes it is true that I AM angry and frustrated and petulant and egotistical. Not to make excuses for myself, but to be a witness is to be truly human, and to be human is to suck sometimes. Witnessing work is done with and by imperfect people who sometimes suck, and who aspire to be better, and kinder, and gentler (like me!).

What is the conversation I need to be having? – To what extent is my hater behaviour constructive. There’s a difference between believing in and advocating for values driven work, and letting ego take over.

What is the thing that is true, that I am pretending isn’t? – My anger is only constructive to the extent that it maintains recognition of empathetic connection. My anger is not constructive if it becomes ego. Witnessing work driven by ego is not witnessing work. I will have moments of ego.

This is rambly. What I really want to say is, God! What the fuck. ??

Question:

How do we avoid becoming bitter in our perspectives on how to do the work?

When does intentionality about the work become policing?

How do I be a good witness to witnessing? (does this make sense)

After spending a week with Okot Bitek’s writing, I’ve been thinking deeply about the kinds of labour that underlie the act of storytelling—especially when the stories are rooted in survival. Okot Bitek’s writing confronts what it means to tell the truth when the truth is unbearable, when the language we have feels inadequate, and when the act of telling is a form of violence.

In Okot Bitek’s 2020 chapter, the labour is not just in survival but in the painstaking act of narration. The chapter grapples with the impossibility of narrating certain kinds of pain—pain that exceeds language. Okot Bitek’s writing is not simply documentation; it’s an offering, a form of narrative labour that seeks to transform private suffering into something communally legible. But even that act of transformation is fraught. She asks: how do we tell stories of atrocity without replicating the harm? How do we work with language that has already been colonized, weaponized, or rendered hollow? The writing here insists that storytelling is not a neutral act—it’s a negotiation, a careful and risky movement between remembering and reliving.

We, the Kindling, offer yet another entry point. Here, silence is not absence but assertion. The refusal to speak becomes its own mode of care, of self-preservation. The work is in the withholding—in not offering trauma up for public consumption. This makes me reflect on who gets to choose silence and who is punished for not speaking “enough ” or “correctly.”

Julie answered a question during the Noted Scholars Speakers Series where she stated that her work is not about women per se. It is about storytelling. I’m thinking through what it means for writing to be more than just the documentation of pain. Julie said that it must be about telling the truth—not simply in the factual sense, but in the sense of writing toward a more honest account of human experience. This means widening the frame, moving beyond individual trauma to think structurally. It means refusing to reduce people to their pain.

I’m also reminded that aspiration matters. The goal is not just to describe what is, but to imagine what could be—to hold space for resistance, for possibility, for futures not yet realized. Writing, then, becomes a way of working toward liberation—not only through what is said, but also through what is made imaginable.

Normally I feel like writing these reflections, often non-linear, is like going through a door to a room full of ideas and walking around inside the room. And this time, I feel like there are 300 doors to open, less of a room and more of a web of things better said by other people. I feel a lot of pressure with this reflection and it is obvious why: we have read many brilliant writers this term and I do often poke around online looking at their blogs or Instagram profiles, but these writers are not typically sitting in a home that used to be mine drinking tea out of a mug I bought to replace one I shattered. So instead, I am sitting here looking at scribbled notes in notebooks and on the flyleaf of We, the Kindling and wondering where to begin.

As I sit here staring at this blank page, I looked out at the trees referred to in the “Place of Many Trees” and thought that these are really not so many trees in the grand scheme of things. And then I watched this pair of people under umbrellas walk up to the trunk of a stalwart red cedar, put their palms against it, and talk to each other around its breadth for a few minutes as they held onto its bark. Julie made note of being asked recently by a student: what is the role of the land as witness? The next day, Daniel Heath Justice noted that in We, the Kindling, “the women are never alone because the land is their witness,” providing an answer to a question he didn’t hear. Maybe the many-ness of the trees is not in how many trunks and branches I can see, maybe it is in the many-ness of the relationships between the trees and the passersby, the moss, the beetles, the coyotes. Maybe every person who reaches out their palm to the red cedar feels a different tree as they take the moment to witness one another’s aliveness. Julie told us she wanted to write something about trees and people in conversation, and as I revisited these readings today, they all feel at least a little bit about trees and people in conversation. The trees bear witness to Rooster Woman nine times in twenty pages, and Julie finishes her chapter with, “so we pass on stories and whisper to the bark of trees that still stand against the wind” (263).

I brought a friend from Non-Grad-Student Life to Julie’s book launch and after, she wanted to look closely at the tapestry. I stood there, explaining the process of its creation and pointing things out. She too, began pointing things out to me depicted in the tapestry – things I had never noticed(!) – and I have spent a decent amount of time gazing at its intricacies. This moment reminded me – distantly – of Julie saying that while she had written the book, she was still learning to read it because Erin had pointed out that Rooster Woman ends where it began and this had not occurred to her while writing. Our familiarity with something does not beget all interpretations that bear truths. And so for this, I return to what Julie said in her teach-in that made me scamper out of the room to get my notebook: We are often so certain about what is right and wrong and what is happening and untrue, but what is it that we do not know? And so “what is our responsibility to what we don’t know?” I noticed in this question, Julie says “we” and “our,” which speaks to her later assertion at the launch that the “‘we’ is easier than the ‘I’ and sometimes more true … the plural is always important.” I know it is brazen to assume, but I think in this context, Julie was both speaking for herself – in her responsibility to what she cannot know – and calling us to action, asking us to really determine our responsibility to the unknown. We bear both a collective responsibility to that which cannot be known (which, if I were writing a 4000 word reflection, I would tie back to our earlier conversations this term on silence and agency but I will just have to save that for happy hour or something) and an individual responsibility to what we do not know in the moment of witnessing, writing or remembering.

I just loved this week, Erin, in so many ways. It would have been a gift just to do the reading, to have the referral. But the moments in between were unspeakably impactful in ways I cannot yet put to words. So while all this about how we think and how we write and see and remember and witness was marvellous, what I will remember best is this: sitting in the living room, Julie advising us to: “hold onto ourselves as much as we can and hold onto each other.” To put our palms out to one another, hold onto the bark, to reach for each other’s hands and to tell truths that insist on themselves.

My question is this: Why do we want or need to know what we are witnessing while we are witnessing it? What are we seeking?

Ever since having had the privilege to have the conversation with Julie, I have been trying to think how I am going to start this post. As I am writing this, I have all the notes I took during Julie’s teach-in and the book launch, and I also have the book in front of me and I have the readings open on my computer, and it’s almost as if I am begging them to give me an answer of how to make sense of my thoughts. I ask for patience when you read this.

Thinking back to Julie’s introductory question during our conversation on Tuesday about how do we understand to bear witness/what is to bear witness, I immediately thought about how we are all witnessing mass atrocities, and genocide, and violence across the world but not all of us are actually bearing witness. What is to bear witness? Who gets to bear witness? Answering these questions right now is just as difficult as it was on Tuesday, and maybe even more so. I think the thing I keep coming back to is that to bear witness, I need to be ready to listen to a story. If we (me/you/us) are not ready what happens is that, as Julie puts it, “they [the witness] saw us but maybe not in the way we wanted to be seen.” Daniel Heath Justice put it beautifully by saying that to be a witness is to work through the grief, to listen to each other, to comfort each other.

Stories/storytelling were also an important aspect of this week. And there are a couple of things that I keep circling back to. The first one, is what Julie said about fiction as a genre. How fiction can be a liberating genre because you do not need an exact place, or time, or name, to tell something. That does not mean the story is any less true. And the second thing is that stories all start with someone saying “I am ready to tell my story” and in the act of reading/listening to the story, that person has actually told the story. For at the end of the day, what is a story with nobody to listen?

The last thing I want to touch upon in this very discombobulated reflection, is the land, the animals, and the environment as witnesses. Land remembers, and the Palestinian land will remember the genocide. The bodies of water remember; the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande will remember the migrants looking for a better life, the Mediterranean Sea will remember all the capsized boats full of migrants trying to escape violence. The land and the water and the animals will witness and will remember, even if/when nobody else does. Daniel Heath Justice said something that really touched me, in talking about the women whose stories make up Julie’s book. which is “The women are isolated but they are never alone because the land is there.”

As soon as I have the time to do so, I very much look forward to reading “We, The Kindling”, and re-read it. I look forward to becoming part of the story and bearing witness. I look forward to listen to other stories. I look forward to being ready to listen to a story.

I forgot to actually put my question: how do we know when are ready to listen to a story? how do we know when we are ready to tell a story?

This week’s readings took me back to my time as a literature student over a decade ago, reading Thiongo, Conrad, and Morrison for my post-colonial literature class. Juliane’s article helped me dust off those learnings, reminding me how storytelling is an act of bearing witness that goes beyond mere documentation. I grew up in the 90s in Abu Dhabi, surrounded by migrant families from across the Middle East, including Palestine.

When I was born, the Palestinian nurse who attended to my mother gave her a pendant with “Palestine” inscribed beneath an olive tree. For years, this symbol was just a token of affection between two women who shared a deep bond in a small duration of time, but my own anagnorisis – the moment of recognizing the reality behind it – came more than a decade later when I went to journalism school and learned about the history of Palestine and journalism coming out of there. Later as a journalist, I witnessed how stories of trauma and suffering were compressed into transactional headlines, failing to capture the fullness of individual or collective memory. I approached these stories with the misplaced intent of “giving voice to the voiceless”, but now, I realize what I was doing wrong. wish I had read Juliane’s article then – it offers a deeper understanding of “re-memorying” and re-storying injustices, emphasizing the storyteller’s responsibility to respect the experiences and resist the temptation to reduce people to their stories of pain.

This week’s readings also reminded me of Alexa Koenig’s article on bearing witness in the age of social media. Link here: https://time.com/6314011/doomscrolling-find-meaning-online-essay/. Much like any technology, social media’s impact depends on how it’s used. While platforms have enabled organizations like UC Berkeley’s Investigations Lab to uncover injustices through open-source intelligence, they also risk enabling doomscrolling and psychic numbing. Koenig suggests that mindful engagement and purpose-driven witnessing can transform this passive exposure into ethical solidarity and meaningful change.

Hammad’s reading carried a heaviness that I felt, especially their insight that denial is often a willful turning away from knowledge. I felt Hammad’s exhaustion when she wrote, “The big emancipatory dreams of progressive and anticolonial movements of the previous century seem to be in pieces, and some are trying to make something with these pieces, taking language from here and from there to keep our movements going.” I resonated with their observation that “turning points” are often visible only in hindsight. For India, this turning point was Narendra Modi’s election as Prime Minister in 2014, which ushered in an era of normalized violence against minorities, including Muslims, Dalits, and Christians. I also fear that the continued erasure of Palestinian suffering legitimizes similar violence against marginalized communities in other countries. India, once among the first non-Arab nations to recognize Palestine, has seen its stance shift under this new government. Her discussion of nostalgia as a hindrance to truthful remembering reminded me of our earlier discussions around memory – nostalgia, while emotionally powerful, often obscures the specific stories and material conditions that shape collective memory.

This week’s conversations with Julie about witnessing demonstrated that this act carries both the weight of presence and a sense of responsibility. It’s not just about seeing, but it’s about carrying what we’ve seen and deciding what to do with it. Reading We, the Kindling and Isabella Hammad’s exploration of cognition, I was wondering about when we truly know something and how that knowledge has the ability to change us. When this question is placed in the context of war, displacement, and history, it stops being theoretical, and it becomes personal.

Julie’s story about Rooster Woman really stuck with me. The idea of return and repetition, specifically of returning to a name, a home, a sense of self, felt impactful. She asked why knowing doesn’t always lead to change, even though we expect it to. She also asked, “How can 60,000 children disappear in Uganda, and the world continues as if nothing happened?” The reality is that just knowing something doesn’t guarantee a change will come, but knowledge remains important because it transforms the silence that can accompany knowing into a choice. It can promote neutrality and perhaps moral injury in the deliberate choice of not acting or speaking on something.

This week, with the strike and Palestinian action, I’ve been thinking a lot about my own identity, my connection to Lebanon, and my responsibility in representing it. The conversations we’ve had in class have helped me make sense of things I’ve been carrying for a while. Talking with Julie, we were reminded that witnessing demands action, even if that action is speaking up, refusing to let something disappear into silence.

During class, I read aloud Hossan Shabat’s last words: “I ask you now: do not stop speaking about Gaza. Do not let the world look away. Keep fighting, keep telling our stories—until Palestine is free.” It’s easy to feel small in the face of everything happening, but his request solidifies that saying something and acting along with witnessing matters. Silence makes injustice feel as though it belongs, but witnessing means refusing to let it happen.

Julie also talked about the idea of land and nature as witnesses, which I thought was really interesting and reflective of Indigenous traditional practices. Water carries memory and holds the stories of those who have gone through it or have walked around it. The land absorbs history, and trees reflect changes in time and environmental factors. Memory is held in so many spaces and kept alive in so many ways.

The one questions I am still left with are: What does it means to truly carry knowledge and How I decide when or how to act on it?

In this week’s readings, Tony Morrison’s concept of ‘re-memory’ captured my attention. For Palestinians, re-memory is not only about recalling the past but actively resisting its erasure. It is found in the stories of elders who remember the olive groves and the scent of jasmine in their childhood homes before the Nakba of 1948. It is in the murals and poetry that reclaim Palestinian identity amidst intentional attempts at its destruction. It is in the oral histories passed down to children who have never seen their grandparents’ villages but hold their names close to their hearts. Re-memory is a radical act of survival, ensuring that even as history is misconstrued by colonial powers, the truth remains inscribed in collective consciousness. I feel this is where our responsibility as witnesses take shape. I grew up without having learnt about the genocide of the Palestininan people, but I will make sure another child in my family doesn’t. I engage in discussions about Palestine with my father to make sure I am talking about it actively. I identify projects donating money to Palestine for my brother so he can pay his Zakat this way. I do not have the power to stop this genocide; but I hold the power to remember and educate and that remains my responsibility as a witness.

Isabella Hammad mentions the following words by Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov in the context of World War II, ““1939 did not exist in 1939, there were just mornings when you woke up with a headache, uncertain and afraid.” The observation that history becomes history only after the fact painfully resonates with Palestinian trauma. The world may one day look back at this genocide with the clarity of hindsight, but for those living through it, each day is a new horror, a new uncertainty. Each day Palestinian people wake up to new tragedies. Each day someone loses a mother, a father, a child, a friend, a sister. As the crisis unfolds, the narrative imposed by global powers seeks to blur its reality, making it seem as though history is not being made in real-time. Yet, in the resistance of the Palestinian people, in their steadfast denial to disappear, there is the possibility that this moment of suffering will not simply be seen as a tragic inevitability but as a turning point in their struggle for liberation. We do not know if we will live to see this liberation in our generation; but we can hold hope for it.