Towards Accountable Relationships and Relationship Building with Indigenous Peoples and Communities

Since the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada in 2015, we have seen an exponential increase in the number of Indigenous faculty and staff being hired in universities, as well as increased recruitment of Indigenous students, and mounting interest in Indigenous knowledges, and collaborations. While at face value, this is good news, this rapid growth has also surfaced and made visible the endurance of colonial patterns and relationships, including the consumption and tokenization of Indigenous Peoples and knowledge systems (Ahenakew, 2016; Daigle, 2019; Gaudry & Lorenz, 2018). In this article, I offer a social cartography and an educational tool that can support both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to see the complexities, tensions and paradoxes that have emerged in the recent spike in interest in Indigenous engagement.

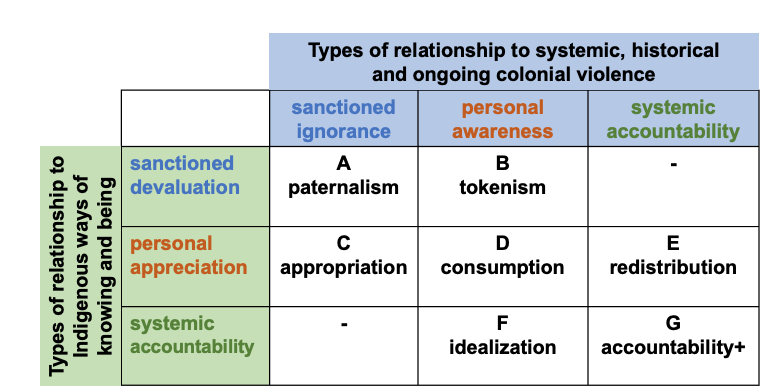

The social cartography, co-created with the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (GTDF) Collective, cross-references attitudes toward colonial violence with attitudes toward Indigenous knowledges. The educational tool is a “Frequently Asked Questions” resource, with questions I have collected over the past five years, primarily from non-Indigenous students, in relation to Indigenous research, education, identities, and the politics of Indigenous-settler relations. In refusing the usual colonial expectations and standards for academic articles, I invite readers, especially non-Indigenous readers, to approach the experience of reading this text as a pedagogical and diagnostic exercise as a means of evaluating their capacity to build relationships with Indigenous individuals and communities based on trust, respect, accountability, consent and reciprocity (Whyte, 2020).

Fast tracking lessons already learned

I am part of the GTDF Collective, which is a collective of researchers, educators, artists, activists, and Indigenous knowledge keepers working at the interface of questions related to historical, systemic and ongoing violence and questions related to the unsustainability of colonial systems vis-a-vis the limits of the planet. Part of the work of the collective has focused on problematizing colonial desires for Indigenous engagement, including the desire to consume Indigenous knowledges (Jimmy & Andreotti, 2021) and self-interested desires for “allyship” (Jimmy, Andreotti & Stein, 2019). In Towards Scarring Our Collective Soul Wound (Ahenakew, 2019), I have explored the burdens and expectations placed on Indigenous people (see poem “Academic Indian Job Description” , Ahenakew, 2016). In piloting these resources with different Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups, we have also tried to map what, educationally, could help ground non-Indigenous people in their learning and unlearning journeys, considering the common circularities that tend to emerge and the high costs of this learning for Indigenous individuals and communities.

In our workshops about these issues, we usually start with five propositions that can accelerate the process for non-Indigenous people to confront their complicity in colonialism, and expand their capacity to interrupt harm and repair relationships. These propositions are framed as “5 fast tracking lessons already learned” that can help prevent settlers from repeating mistakes that have already been made several times, usually at the expense of Indigenous peoples.

These lessons are:

1) Tokenism wastes time and resources: Indigenous individuals and communities can see when organizations are focused on the optics rather than the substance of the engagement. As a result, “business-as-usual” or “window dressing” forms of engagement and reconciliation generally backfire with reputational and relational costs for the organization.

2) Settlers have a debt to Indigenous peoples: Canada’s ideals of progress and prosperity have been realized at the expense (rather than only the exclusion) of Indigenous peoples. There is therefore a debt owed by settlers to Indigenous peoples. However, settlers usually frame their Indigenous engagements as forms of concession or charity, which in turn often manifests as paternalism and assumptions of settler benevolence.

3) Indigenous peoples and communities are diverse and complex: Some Indigenous peoples embrace Canada and its ideals of progress wholesale, some Indigenous people reject Canada and its ideals of progress wholesale, and most Indigenous peoples are somewhere in-between. There is a lot of diversity within and between Indigenous communities; there are also, like in all communities, intergenerational conflicts and struggles for power and status within communities. There is no one “Indigenous perspective” that represents all Indigenous peoples (“Pan-Indigenism”, which was popular in the 60s, is not politically credible today). How Indigenous peoples respond to situations depends on a number of factors, including the expectations of a particular context, the roles being played, obligations and accountabilities that need to be fulfilled, and whatever else is happening in Indigenous peoples’ lives at personal and community levels. Expecting Indigenous peoples to speak with one voice or demanding an Indigenous person to fit in one box is both harmful and unrealistic.

4) Romanticizing Indigenous cultures is not sustainable over the long haul: It is common for settlers to move quickly from pathologizing and deficit-theorizing Indigenous peoples to romanticizing and idealizing them. Fred Moten has talked about this phenomenon as a shift from treating marginalized people as “subhuman” to treating them as “superhuman.” It is unfair to impose on Indigenous Peoples (and other systemically marginalized groups) unrealistic standards of humanity. While romanticization can sometimes lead people to commit to solidarity, as soon as those romanticizing face the complexities of real Indigenous individuals and communities, their motivation often turns to resentment and the support disappears. Projections and idealizations imposed by settlers get in the way of generative relationship building.

5) Indigenous forms of relationality and accountability are hard and require long-term commitment: Relationships that are sustainable in the long term are built on trust, respect, reciprocity, consent and accountability, but each of these words can mean something different than what you might expect and has different layers of depth. The process of relationship building will likely take several years and involve many mistakes. There is no checklist or formula for relationship building that can work across all timescales, contexts and communities.

When I present these propositions, I generally ask people to do three things. First, I ask them to observe how different parts of themselves respond to the propositions. Then I ask them to trace where these responses are coming from and the implications they would have for their ability to weave relationships with Indigenous peoples. Finally, I ask them to focus on the last sentence of the last proposition, which emphasizes that there is no formula or solution for settler-Indigenous relations that will work in all situations. The colonial desire for quick fixes, formulas, checklists and universal solutions is one of the greatest obstacles to being able to weave relationships in ways that account for the weight of historical harms and the complexities and challenges of interrupting (often unconscious) colonial patterns and learning to co-exist differently.

Accountability +

I often follow-up this exercise with the propositions with a presentation of the social cartography “Accountability+”, which was tested and refined with the support of many Indigenous colleagues. This social cartography cross-references three common attitudes toward colonial violence with three common attitudes toward Indigenous knowledge systems.

The three common attitudes toward colonial violence are:

Sanctioned ignorance (e.g. “Colonialism happened in the past and has no bearing in the present”)

Personal awareness (e.g. “Canada should apologise for harms done to Indigenous peoples”)

Systemic implication (e.g. “As a settler I benefit from historical and ongoing dispossession and genocide of Indigenous peoples and I am answerable and accountable to ongoing violence towards Indigenous peoples”)

The three common attitudes toward Indigenous knowledge systems are:

Sanctioned devaluation (deficit theorization of Indigenous experiences and worldviews)

Personal appreciation (consumption of Indigenous experiences and worldviews for settler self-actualization)

Systemic accountability (capacity to sit with the weight of the trauma and pain beyond individual shame and romanticization of Indigenous peoples; commitment to support Indigenous peoples to revitalize their cultures, languages, educational systems and livelihoods)

The cartography creates a matrix of these 2 sets of attitudes that result in 7 dispositions:

The first disposition (A) is paternalism. This disposition encompasses both an attitude of sanctioned ignorance towards colonial violence and an attitude of deficit theorization towards Indigenous knowledge systems. It assumes Indigenous Peoples need to “catch up” with settler society. People who hold this position assume that colonialism represents progress and ultimately benefited Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Peoples’ knowledges are perceived as backward misconceptions, traditions, and beliefs that need to be corrected and the successful correction is a testament to the superiority of settler knowledge. It is important to name that sanctioned ignorance and devaluation of Indigenous peoples’ knowledges have been used to justify genocidal practices that go far beyond paternalism, as in the case of the Indian Residential School System.

The second disposition (B) is tokenism. Tokenism combines personal awareness of colonial violence with sanctioned devaluation of Indigenous knowledge systems. Tokenistic land acknowledgements illustrate this disposition, wherein Indigenous elders are asked to start a conference, and then people are eager to move on with the program without substantial engagement with the Elder or the knowledge they hold, or the implications for what follows.

The third disposition (C) is appropriation. Appropriation happens when people are not aware of (or do not acknowledge) their complicity in systemic colonial harm or the history of the theft of lands, livelihoods, lives, knowledges, languages, stories, and objects. This leads people to feel like they are helping Indigenous People by “promoting” their culture, when in fact they are using this culture for personal gain and inadvertently reproducing the same colonial harms.

The fourth disposition (D) is consumption, in which people combine personal awareness of colonial violence (without substantial self-implication in systemic violence) with personal appreciation of Indigenous knowledges in a way that is (usually) idealized and instrumentalizes their engagement with Indigenous peoples as a means to enhance their perceived moral virtue and social capital (see Jimmy & Andreotti, 2021).

The fifth disposition (E) is redistribution, which combines a self-implicating critique of systemic colonial harm with personal appreciation for Indigenous knowledges (without substantial commitment to Indigenous engagement). This disposition acknowledges the need for support for Indigenous-led initiatives and spaces, but (for different reasons, including legitimate contextual reasons) does not get substantially involved with Indigenous initiatives and relationships.

The sixth disposition (F) is idealization, which combines long-term commitments towards Indigenous knowledge systems and communities and personal awareness of complicity in harm, without self-implication in systemic violence. The idealization is not only problematic for the reasons discussed before, but it also works to deflect self-implication in colonial violence. An illustration of this would be someone who has committed to attending Indigenous ceremonies as a way of not having to face more difficult aspects of settler accountabilities.

The seventh disposition (G) is accountability plus, which combines systemic accountability in relation to both self-implication in harm and Indigenous knowledge systems. This disposition requires a substantial commitment to the long haul of relationship building based on respect, trust, consent, reciprocity and accountability (Whyte, 2020) This disposition entails an expanded capacity to engage with the heterogeneity of communities, paradoxes, complexities, pushbacks, frustrations, failures and mistakes. This disposition only becomes possible when the “5 fast-tracking lessons already learned” are internalized.

In my experience, disposition A is the most harmful; dispositions B, C, and D do more harm than good; dispositions E and F can do more good than harm, but, especially in disposition F, there is high potential for romanticization and precarious commitment. Disposition G has the most potential for harm reduction and harm interruption in the long term. However, the impacts and implications of each disposition depend on the context in which they manifest. When I present this social cartography, I generally ask people to do three things: 1) to identify which disposition is most predominant in their professional context; 2) to trace why this is the case, and the implications of this for Indigenous communities; and 3) to identify steps that would be necessary for their organization to move toward more generative dispositions.

In the second part of this paper, I present an educational resource that consists of several frequently asked questions that I have received over the past five years. I generally point people to the online version of this FAQ after presenting the five propositions and the Accountability+ social cartography and give people time to review the FAQ and to ask further questions.

Educational resource: FAQ

This FAQ educational resource was originally developed for two courses that I teach: one on Indigenous Research Methodologies and one on Indigenous Education. My experience with these courses illustrate the shifts we have seen after 2015 in relation to interest in Indigeneity. Prior to 2015, these courses had modest enrollments, made up primarily of Indigenous students. Since 2015, the demographics have shifted significantly, and today the courses attract primarily non-Indigenous students and are often over-enrolled. Because of this change, I have had to redesign the courses with this non-Indigenous audiences in mind. I also noticed that I received many common questions from non-Indigenous students, which point to the systemic nature of the challenges and complexities of fostering more generative and less harmful engagements with Indigenous peoples and knowledges.

This led me to develop a FAQ resource in order to redirect common, seemingly benevolent yet harmful desires for engagement with Indigenous peoples, knowledges, methodologies, research, and communities. The FAQ format also indicates to students that the issues I name are systemic rather than individualistic, but they are also implicated in them. I have grouped these questions under five categories related to questions about: research, teaching, learning about colonialism, Indigenous identities and contemporary complexities.

One of the pedagogical reasons to create this resource was to prepare students to face the complexities and heterogeneities of Indigenous communities. Thus, I emphasize that these are my own responses and that I do not speak for all Indigenous Peoples. Other peoples’ responses might be harsher than mine, while some others might be more appeasing, but I emphasize that the students need to be prepared to encounter Indigenous peoples’ anger, frustration, and refusal if their aspiration is to work with Indigenous peoples.

Research-related questions

As a non-Indigenous person, should I use Indigenous methodologies in my research?

This is a very common and very difficult and controversial question. In my personal view, it is only ok for non-Indigenous people to draw on Indigenous methodologies to carry out their research if they understand and acknowledge that, because they have not been socialized in Indigenous protocols, ceremonies, relationship building and sensibilities, their use of these methodologies will likely be completely different from what was originally intended by Indigenous peoples. I advise my students to position themselves clearly and with a lot of cultural humility when they approach this issue in their work. If they decide to draw on Indigenous methodologies, I advise them to say that their research methodologies were “inspired by” or “informed by” Indigenous approaches rather than say they are “using” these approaches. Some Indigenous people think that non-Indigenous people using Indigenous methodologies is inappropriate and a form of cultural appropriation. Sometimes I also tell students that Indigenous methodologies do not fit their project. This depends on what they want to do and how they are positioning themselves in relation to Indigenous peoples. It is important not to treat Indigenous methodologies as a product on a supermarket shelf of methodologies that consumers can choose from.

I want to work with Indigenous people for my research and in the future, where should I start?

Learn about colonialism, and how your history and positionality intersect with it and are shaped by it, and then educate yourself about Indigenous struggles long before you start to attempt to build relationships. Learn about how different Indigenous peoples “read you” as a settler in Canada. The real starting point for you is learning to build relationships differently, in ways that are grounded on trust, respect, reciprocity, consent and accountability (Whyte, 2020). This form of relationship building neither deficit-theorizes (or pathologizes) nor idealizes (or romanticizes) Indigenous (or non-Indigenous) peoples. Most Indigenous people operate from different senses and sensibilities than settlers (see Jimmy, Andreotti, & Stein, 2019). Be mindful that you will be building relationships in a context of historical conflict and therefore you should not expect Indigenous people to be necessarily excited about you wanting to engage with them or with your research project. Be aware that, given the violent history of settler-Indigenous relations in Canada, there could be legitimate mistrust and resentment towards settlers in Canada, particularly researchers. Many researchers have engaged with Indigenous communities before, only to cause a lot of damage (Tuck, 2009; Tuhiwai Smith, 1999). If you decide to do it, you will likely be seen with some suspicion and building trust can take years, even for Indigenous researchers working in their own communities. Therefore, if you are planning to involve Indigenous people in your research three years into the future, you should start building community relations now, so that the Indigenous communities can guide you as to what kind of research they would be interested in collaborating with you around.

What would ethical research in collaboration with Indigenous peoples look like?

It would be different from the colonial pattern whereby non-Indigenous students and even professional researchers decide on a research topic of their own choice related to Indigenous people without understanding the context or consulting the Indigenous community, and they expect Indigenous individuals or communities to help them complete their projects – and be grateful for the “opportunity” to do so. These non-Indigenous students/researchers usually think that their research project is a way of “helping” Indigenous communities, but the communities may see it very differently: they may see these students/researchers as treating them as “data” to be harvested, which extracts time, knowledge, and resources from the community. They may also see the research as something that uses their suffering to build someone’s academic career. Research projects that are not sensitive to these issues often ask Indigenous peoples (as “research subjects”) to work for free, which is a very common form of cognitive exploitation. If you are going to do research with Indigenous peoples, make sure that you have long-standing relationships, that you have a system of reciprocity that serves the Indigenous people you are working with on their terms, and that, preferably, your research is effectively led by Indigenous peoples’ concerns. Most Indigenous people will say “nothing about us without us”. Some Indigenous people will say that all Indigenous research should be led by Indigenous researchers. Especially if you are new to this, it is important to keep in mind that this is difficult work that requires a lot of unlearning. As this unlearning happens, people usually make a lot of mistakes. While mistakes are important and inevitable, the most responsible thing to do is to be humble and attentive to the different types of labor that your un/learning creates for other people. It is also important to accept responsibility when you do make a mistake, and learn from it so as not to repeat the same mistake again. The poem “Wanna be an ally?” talks about the difficult things that are necessary to build ethical relations with Indigenous communities (GTDF, 2019) .

I have a methodology, process or practice that is very relational (or ecological) and I believe that Indigenous people would benefit from what I have to offer them. Where can I find Indigenous individuals or communities that want to collaborate with me?

Indigenous relationality and ecological sensibilities are different across and within communities. The stereotypes of the Indigenous eco-warrior and of the Indigenous shaman who brings peace to the world, although still useful in certain contexts, are idealizations that romanticize Indigenous struggles and undermine Indigenous self-determination in the long run (Jimmy & Andreotti, 2021). There are many non-Indigenous people who believe that their practices or methodologies can map onto Indigenous practices and methodologies, but their understanding is based on stereotypes and false and harmful equivalences between non-Indigenous and Indigenous knowledges. Indigenous practices and methodologies are complex and multi-layered and they require a lifetime of discipline for someone to have even a basic understanding of them. Unfortunately, the desire to collaborate in this way is a colonial and paternalistic desire that is understood by many Indigenous people to be a way of instrumentalizing and appropriating their knowledges for non-Indigenous agendas (Ahenakew, 2016). Engagements with Indigenous knowledges should be grounded in ethical and political commitments to support Indigenous peoples’ self-determination, and relational commitments to approach those knowledges with humility, reciprocity, and accountability. Because non-Indigenous peoples’ desire for collaboration on these problematic terms is so common – Indigenous peoples receive lots of requests like this – we have had to develop strategies to refuse engagement, so you will probably face a lot of Indigenous silence or non-compliance if you insist on this approach.

If I take many courses on Indigenous knowledges and research, or if I do my research on Indigenous issues, will I be able to find a job in the future in areas related to Indigeneity?

In Canada, jobs advertised with an Indigenous title are expected to be filled by Indigenous people, often Indigenous peoples from Canada (First Nations, Metis or Inuit). Fields like Indigenous Studies will also look for Indigenous scholars (especially from the local area) for their open positions. If you are not Indigenous from Canada, it will be almost impossible to be chosen for a job advertised with an Indigenous title in Canada. Having said that, it may be really useful and valuable to have courses related to Indigenous issues on your transcript or your CV. Since the Canadian government has declared its commitment to Truth and Reconciliation, and many institutions and organizations have started to engage in processes of Indigenization, and decolonization, it is fair to say that Indigenous issues are now part of any job within and outside of academia in Canada. Therefore, educating yourself about Indigenous knowledges and research may indicate to employers that you are better prepared for the challenges ahead in any job, and for working ethically with Indigenous peoples in any sector.

I have taken courses on the Two-Eyed seeing approach and I feel pretty confident that I can work well with Indigenous peoples. Do you recommend this approach?

Unfortunately, there is no approach or formula that will work in all contexts, at all times and/or for all Indigenous peoples. In my view, the Two-Eyed Seeing approach has been really important as a first step when people are starting to notice the differences between settler and Indigenous ways of doing, thinking, relating and being. It also interrupts the desire by some settlers to “integrate” Indigenous knowledges into Western frames to create a revised universal truth. However, inevitably, especially in order to be intelligible to non-Indigenous peoples, it has simplified the issue in order to offer an entry point into the subject. Since its introduction, Two-Eyed seeing has been taken up and used in many different ways by both Indigenous peoples and settlers. Some of these ways have been non-generative, for instance, when settlers approach “Indigenous knowledge” in pan-Indigenous ways that fail to acknowledge that there are not just two ways of seeing, but multiple different Indigenous knowledges as well as other non-Western knowledges – and different Western knowledges or paradigms as well. Sometimes settlers have claimed that they as individual knowers are engaged in Two-Eyed Seeing, rather than understanding it as a means of bringing together the insights of different knowledge communities, in ways that respect the value of those knowledges and the integrity of each. At its most generative, a Two-Eyed seeing approach can serve as an interruption of the common desire for universal knowledge, and a reminder of the situated nature of all knowledges and ways of knowing (seeing). Respect for (onto)epistemological pluralism can be found in many Indigenous knowledge systems (Andreotti, Ahenakew & Cooper, 2013; Reid et al., 2021). Settlers who want to apply Two-Eyed seeing as a universal or pan-Indigenous approach will likely face many push-backs, especially from Indigenous peoples. Nowadays, as the discussion about settler-Indigenous relations has become more complex and is also changing at a faster pace, it is important to pay attention to the depth of the challenges and the difficulties of settler-Indigenous relations.

Teaching Indigenous content

How do we apply what we have been taught in this course in K-12 schools?

If you have gone through teacher education you will probably expect my courses to give you something safe (guidelines or resources) that can be applied in the classroom. However, graduate education is about interrogating “common sense”: your ideas, positionality, society, institutions, schooling, and also interrupting the desire for formulaic answers. In graduate studies, students are expected to go through their studies unpacking what they knew before in order to develop the depth and breadth of understanding to decide for themselves what is the next step for their work in their own contexts. When they leave the course, they are better prepared to face the fact that things are complex and complicated, and that very often even the best “solutions” create unanticipated problems. The intention is that this preparation will prevent you from becoming immobilized by this complexity, and instead enable you to make difficult, context-specific, self-reflexive, “imperfect” interventions in practice, and further, to accept responsibility for the outcomes (both intended and unintended) of your choices. Each K-12 school will require specific, situated interventions in order to meet contextual needs. In addition, while I understand that the question comes from a place of someone wanting to do “the right thing,” this can also be considered an unfair question to ask of Indigenous people.

As a non-Indigenous teacher, should I be teaching Indigenous content?

If Indigenous content is a required element of your curriculum, then you will need to teach it. My courses prepare you to identify the ways to do it that can be harmful, but it does not tell you what the “right” way is, because that depends on the context. If you have to integrate Indigenous content into your curriculum, the right answer for your context will depend on a number of factors like: the quality of relations with the school’s local Indigenous communities; the degree of support from principals and other teachers; the availability and willingness of Indigenous people to work in partnership with you (and the availability of resources to compensate them for their time and labour); the availability and quality of resources and support for teachers; the training available for this kind of work; the stamina of everyone involved for a long and difficult process; etc. Perhaps a more useful question could be “What is the most responsible small next step for me to take in my context?” The courses I teach aim to prepare you to engage with Indigenous peoples and Indigenous content through an approach rooted in cultural humility, self-reflexivity, and an understanding of the depth of the challenges and the difficulties of Indigenous-settler relations today. The courses are also designed to prepare you to role-model for your students and colleagues the importance of building relations with Indigenous peoples grounded in trust, respect, reciprocity, consent and accountability.

Learning about colonialism

Why do we have to learn about depressing things that happened in the past? Why can’t we just focus on the future and move on to a better place together? I want to be told what I need to do to get it right and not feel guilty about something that I did not do.

These are very common feelings that arise and that need to be acknowledged before anything can happen. If we do not understand the past, what brought us here, we will continue to repeat it. Education is usually thought of as something that should make us happy and more fulfilled, but this kind of learning about the past is difficult, uncomfortable and often painful and that is why people resist it. Our formal education has mostly failed in preparing us to hold space for things that are painful, irritating, and overwhelming without wanting to be rescued from the discomfort. This prevents us from looking at the past and the present with honesty, maturity, sobriety, discernment and accountability, which are essential for building more ethical, equitable futures. Although you may feel that you did not do anything wrong in relation to Canada’s colonial history, you still benefit from the wrongs that were done in the past and the wrongs that continue in the present. Our livelihoods are underwritten by a system that is not only harmful to Indigenous communities, but also unsustainable for the continuity of life on a finite planet. We all have the responsibility to interrupt the violence, to repair relationships (including relationships with the land and with non-human beings), and to be accountable: to learn from past wrongs, to address the present impact of those wrongs, and to only make new mistakes in the future, taking into account our responsibilities to current and future generations.

Should we ask Indigenous people to teach us about colonialism?

The answer is “it depends”. While non-Indigenous people unquestionably need to learn about the historical, systemic and ongoing violence of colonialism, retelling stories of harm can be very re-traumatizing for Indigenous people and many are refusing to do this heavy work, although others do it professionally (and often get burned out). In their book Towards Braiding Jimmy, Andreotti, and Stein (2019) give an overview of what to consider when inviting Indigenous people to teach, including appropriate compensation for Indigenous people’s time, labour and expertise (see pp. 41-54).

Non-Indigenous people can do some of this homework on their own by engaging with videos, recorded testimonies, and books. Although learning about histories of harm is really important, it is insufficient to change the colonial ways people have been conditioned to think, feel, hope and relate. In other words: interrupting colonialism is not about changing one’s “mind”, but changing one’s way of relating to oneself, to other beings, to the land and to the world at large. Having good pedagogical containers for this life-long and life-wide unlearning is not the same as participating in a book club. I recommend the book Hospicing Modernity: Facing Humanity’s Wrongs and the Implications for Social Activism (Machado de Oliveira, 2021) as a source of good pedagogical containers.

Should I participate in Indigenous ceremonies, if I am invited?

While many Indigenous people really enjoy sharing their cultural practices and ceremonies, some Indigenous people are also against this type of sharing, their reason being that non-Indigenous people tend to selectively extract and “consume” Indigenous content and sometimes even go on to sell it to other people. This is complex and complicated; therefore, the answer to this question will depend on the context and the quality of relationships that you have. In chapter 3 of my book Scarring the Soul Wound (Ahenakew, 2019), I give a few guidelines for non-Indigenous people who want to partake in Indigenous ceremonies based on a course at UBC where we take students to witness a Sun Dance ceremony.

I have had my fair share of personal trauma and I feel I can relate to Indigenous people through my own experiences of oppression and misfortune. Will I be able to connect with Indigenous peoples through this shared experience?

It’s common for non-Indigenous people to try to connect to the suffering caused to Indigenous people by historical and systemic trauma through their experience of personal trauma. Many Indigenous peoples will find this comparison inappropriate, as it often minimizes the extent of the impact of the brutality imposed on Indigenous peoples through colonization. Those who find the comparison inappropriate insist on a distinction between the trauma caused by colonization – sustained systemic occupation of our lands and targeting of our peoples for elimination – and trauma experienced at the level of the individual. The depth of the trauma caused by genocide goes far beyond the individual through its intergenerational impacts. Although some individual trauma might be connected to systemic patterns of violence, genocide is a particular form of violence that results in a distinct category of trauma. In my opinion, we should not compare different types of trauma (this is not a competition); we shouldn’t look for equivalencies, either.

How does colonialism manifest in day-to-day interactions at the institution? What does decolonization look like? How can you identify the working of colonialism when we have been conditioned to see it as normal?

Colonialism manifests in people’s narratives and behaviour (what they say, do, expect and value, what they are able to hear, how they plan, organize, and evaluate, and how they communicate, interpret and process information), affective patterns (what they want/desire, hope for, fear, aspire to, the boundaries of what they can imagine, what they experience as wellbeing and how they process traumas) and relational patterns (what and how they feel connected and accountable to, how they relate to the land and to living and dying). The Towards Braiding offers a basic distinction between “brick” and “thread” sensibilities that I find very useful as a conversation starter about the differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous ways of knowing and being. As for decolonization, I think it is premature to try and imagine what decolonization looks like when our livelihoods remain underwritten by colonialism and when our imagination and capacity to imagine have also been colonized. We need to start the work of interrupting colonial patterns so that we open up the possibility that a form of decolonization (beyond what we can imagine today) can become possible in the future. This demands that we have a different approach to change. The fact that we want to know and have guarantees about where we will arrive in order to start the journey is also a colonial pattern. I believe the path is made by walking, by trial and error, and the most important things about it will be the ones we stumble upon (the ones we could not have imagined at the beginning of the journey).

Indigenous peoples are always pointing to the wrongs of the past and spreading anger and negativity, but the fact that there are Indigenous courses like this and that Indigenous instructors have been hired at the university are proof that progress has been made. Why can’t we celebrate this progress and make things more positive?

This question is usually received as a form of tone policing by Indigenous peoples who are critiquing the system. This demand for optimism and celebration is often understood as paternalistic and patronizing, and as an effort to deflect from the magnitude of the problem and from the work that still needs to be done. Small steps institutions take towards reconciliation, inclusion or equity with regard to Indigenous peoples are fraught with difficulties and are insufficient. Instead of celebrating these baby steps, we should be increasing our capacity and stamina to stay with the challenges and difficulties of the issue. In order for us to be able to heal from colonialism, we need to be able to talk about these things without Indigenous people having to filter what they say in order to not cause distress for non-Indigenous people. These types of fragilities are roadblocks on the path to good relations.

I am an international student and I wish to immigrate to Canada one day. I have never been told about the terrible things that have happened to Indigenous people in Canada. Do you have any advice for people like me?

What happened to Indigenous people here and around the world may also be a topic that is new for Canadian settlers who have been here for generations – and some people would prefer not to know. There may be similar patterns in your country of origin, of violent parts of history that are not told in history textbooks. If you immigrate to Canada then you will become part of a settler-colonial system – you will also be a settler and you will benefit from a system that systemically dispossesses Indigenous peoples. You will need to learn about your responsibilities as a settler, and build stamina for the long road ahead. The “Letter to prospective immigrants to what is known as Canada” (GTDF, 2021) offers a good short synthesis of the colonial past and present of Canada and how colonialism benefits settlers at the expense of Indigenous peoples. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report (2015) and the accompanying Calls to Action are also great starting points.

Questions about Indigenous identities

I find the word settler extremely divisive and I don’t feel comfortable when Indigenous people place that label on me.

Settler is a precise term that describes those who literally “settled” – i.e., occupied – Indigenous lands, enabled and encouraged through the policies of the Canadian government. Many Indigenous people use it as a technical term to remind people of the violence of the creation of Canada as a settler colonial state. Many Indigenous people also emphasize that settler colonialism was not an event but instead an ongoing structure that continues to dispossess and displace Indigenous peoples. Thus, those who are descended from the early settlers are still settlers today. Settler colonialism was only made possible through a divisiveness that can only be addressed if Indigenous people can name the world as they see and experience it.

I am white passing, have no contact with Indigenous communities, but I have an Indigenous grandparent. Should I identify as an Indigenous person?

We need to look at this situation in many layers. In one layer, colonialism is probably the reason why you have no contact with your Indigenous heritage, so, at a basic level, it is up to you to decide how to relate to the Indigenous heritage of your family. In another layer, claiming Indigeneity is also a political act that places you in a context of historical and on-going struggle where your legitimacy and credibility will depend on many factors, especially the relationships you may or may not have with the community you are claiming association with. In this layer, Indigeneity is about a political community; if you are not claimed by the community, you cannot claim them. In another layer, since many institutions are hiring Indigenous people, claiming Indigeneity is also done for reasons related to economic/career opportunities. This is where it gets even more complicated because organizations will generally prefer to hire people who have a sensibility that is closer to theirs. Therefore, rather than hiring someone who grew up in a reserve, who has lived experience of the challenges faced by the communities and/or who speaks an Indigenous language as a first language, organizations will prefer to hire people who identify as Indigenous who have had a middle-class upbringing, who are cis-gender, heterosexual and white passing, who can write in perfect “standard” English, and who they feel will go along with business as usual (and not challenge them too much). Whatever you decide to do in this case, there will be Indigenous people who will support your decision, and others who will criticize that decision. My courses try to prepare you to understand why this is complex and how different Indigenous groups might read you, but only you can decide what to do.

I identify as an Indigenous person in another country. How should I frame my Indigeneity in the Canadian context? Should I apply for Indigenous scholarships and jobs?

If you are Indigenous to a place outside of what is today known as Canada, then it is important to clearly situate yourself as Indigenous from “[x]” country when you are claiming Indigeneity. You may also decide not to claim Indigeneity in Canada in order to respect the struggles and the space of voice of the Indigenous peoples here or to acknowledge your status also as a settler (if this is the case). Indigenous peoples in Canada will have differing opinions as to whether or not you should apply for Indigenous jobs and resources. Some Indigenous people in Canada believe that only Indigenous people who are from here should take positions identified as being for Indigenous people, or that at the very least, they should be prioritized; others suggest that the people who fill these positions should be not just Indigenous to Canada, but also local to the area and speakers of their Indigenous language; still others believe that it is important to have Indigenous peoples from around the world in these roles. As is the case with many other questions, the answer to this question depends on the context, and you will need to decide for yourself whether or not to apply – understanding that those making the decisions have their own answers to this question.

I hear about people being called “pretendians”. How can we recognize Indigenous fraud and what can we do about it?

This is a tricky question, but an important one. Particularly as more (still limited and highly conditional) opportunities and resources become available for Indigenous peoples, there are instances of non-Indigenous people making false claims to Indigeneity in order to access those opportunities and resources. In some cases, the people making these claims have identified a distant ancestor who they claim was Indigenous; in some cases, they actually do have such an ancestor, in other cases, these claims are entirely made up. In either case, however, the individuals in question lack any contemporary relational connection to Indigenous Nations. Most Indigenous peoples believe that Indigenous belonging is not something that one can unilaterally claim, based on affinity, ancestry, or DNA; rather, it is based on whether or not one is claimed as a member by a contemporary Indigenous community. It is important that everyone, including non-Indigenous people, be aware of this pattern of people making false claims to Indigeneity, including as they are making hiring decisions and award adjudications. However, this is also tricky because there is a risk of non-Indigenous people positioning themselves as the arbiters of Indigenous identity. Institutions that seek to hire Indigenous peoples should develop clear and transparent policies around Indigenous hiring and adjudication practices in consultation with Indigenous members of their institutions, so as to defer to Indigenous protocols for claiming community membership, rather than merely relying on individual self-identification.

Aren’t we all Indigenous to some place?

The statement that “we are all Indigenous to some place” was originally used in the 60s and 70s to elicit support and solidarity for Indigenous struggles, but in today’s context it is often used to undermine Indigenous struggles, as it delegitimizes the unique circumstances of Indigenous peoples’ claims. In Turtle Island, similar to the “All Lives Matter” movement, the claim that “we are all Indigenous” has become an effort to invalidate the struggles of people who live under settler occupation. UNDRIP (2007) defines Indigenous peoples as: “inheritors and practitioners of unique cultures and ways of relating to people and the environment. They have retained social, cultural, economic and political characteristics that are distinct from those of the dominant societies in which they live. Despite their cultural differences, [I]ndigenous peoples from around the world share common problems related to the protection of their rights as distinct peoples.” Many Indigenous people have asked allies to consider the impact of general claims to Indigeneity on Indigenous communities and their struggles today.

Contemporary challenges and complexities

Why are there so many problems in Indigenous communities?

First, I should point out the risk of approaching the challenges that Indigenous communities face in “damage-centered” ways, as Eve Tuck (2009) points out. Many of the problems that Indigenous communities face have their roots in the historical and ongoing effects of colonization, including residential schools, forced displacement from and dispossession of their ancestral lands, and various forms of state and state-sanctioned social, psychological, sexual, spiritual, and epistemological violence. When we invisibilize these histories and ongoing legacies of colonial harm that contribute to contemporary problems, we invisibilize the fact those who are culpable for this violence – which includes not only the Canadian state and Canadian institutions (including the educational, healthcare, and justice systems), but also individual settlers who continue to benefit from its effects – have yet to adequately acknowledge, let alone redress, this harm. In this sense, what appear to be “Indigenous” problems are actually problems of colonization that will require sustained efforts and resources to address them. That said, Indigenous peoples need to lead efforts to address these problems, rather than have solutions imposed on them from the outside. Indigenous peoples continue to seek justice and healing on their own terms.

I try to listen to Indigenous people but I hear many conflicting things. How to make sense of all this complexity?

Part of the work of engaging with Indigenous epistemologies is learning to accept that Indigenous communities are heterogeneous, just as non-Indigenous communities are; and Indigenous individuals are complex, just as non-Indigenous individuals are. There is no one “Indigenous perspective”. This is difficult for some non-Indigenous people to accept, not only because people come to this work with their own preconceived ideas about what Indigenous people want and think, but also because they are often seeking to instrumentalize Indigenous perspectives toward a particular end. As a result, complexity and heterogeneity tend to get erased or flattened, and people may simply choose the Indigenous perspective that is most convenient for their own agenda. Alternatively, non-Indigenous people sometimes weaponize this complexity and heterogeneity against Indigenous peoples – suggesting that, for example, if Indigenous communities do not have consensus, then there is no point in consulting with them at all. It is important for settlers to learn how to engage with the complexity and heterogeneity of Indigenous people and communities in responsible ways.

What’s wrong with romanticizing Indigenous peoples?

The question of what is wrong with romanticizing Indigenous peoples relates to the above question about the complexity and heterogeneity of Indigenous peoples and communities. Often, people think that the antidote to the pathologization of Indigenous peoples is the romanticization of Indigenous peoples. However, in many ways romanticization is the mirror image of pathologization: rather than treating Indigenous peoples as less than human (sub-human), or it treats them as super-human. This is harmful for two reasons. One, it is not generally sustainable; while idealized images of Indigenous people can have a short-term impact of eliciting support from non-Indigenous peoples, this support is conditional on Indigenous people living up to an (unrealistic) image or expectation. Thus, when they inevitably contradict this image, the support tends to quickly evaporate. Two, it is an unfair burden to project onto Indigenous people one’s own idea of what they should be, usually based on what is useful to you. In reality, Indigenous people are, like all other people, complex and contradictory. And like all other people, we have within us the capacity for both wonderful and problematic things. Support for decolonization or Indigenous rights cannot be conditional upon romanticized images of Indigenous individuals or communities; this support likely can only be viable and sustainable if it is rooted in a commitment to recognize and redress historical and ongoing injustices at the systemic level.

How should I raise my children as settlers/immigrants in Canada in ways that do not increase the harm towards Indigenous peoples?

Although there is no formula for raising children, one thing I can say is “pay attention”. Don’t assume your children are just innocent and beautiful – they are a sponge for societal prejudices, they are exposed to put-down cultures, they can be cruel. Do not shield them from colonial history; instead, find age-appropriate ways to talk about what has happened and what is happening. Find ways to prepare them for the difficulties of repairing relations, help them to develop resilience, generosity, and humility. With the children in my family, I like to watch a few films that show the violence against Indigenous children in sensitive ways. I use it to open conversations. I have to confess that I also enjoy watching “Brother Bear”, “Moana” and even “Frozen 2” (all cartoons that address Indigenous issues), but the conversations that we need to have after these cartoons must address how these cartoons were made for Western consumption, and we need to interrogate how they present a particular palatable image of Indigenous peoples, how they reproduce Western ways of being in their attempt to represent Indigenous practices, and the implications of stereotypes that may be more positive, but may not represent how Indigenous peoples would have chosen to represent themselves.

Why do you think more people are interested in Indigenous knowledges today?

Part of the answer relates to the contemporary context of reconciliation; part of the answer is that in the face of so many social and ecological challenges, people are starting to realize the limits of relying on one (Western) knowledge system. Although I believe Indigenous people have a lot to contribute to addressing the pressing issues of our time, I don’t think that we have a universal answer or alternative that people are looking for and trying to consume. Indigenous cultures are older and, I would argue, have more established ways of relating to so-called “nature” that doesn’t cause the same level of destruction that Western society has caused. However, instead of trying to replace Western culture, Western society needs to find a way of “growing up,” by figuring out what went wrong. Indigenous people may choose, or refuse, to support this process, but it’s not their responsibility to solve the problems that they have not only not created, but which have also happened at their expense.

If colonialism has indeed been the cause and the driver of the climate and nature catastrophe and Indigenous knowledges and ways of being are the answer, we should have Indigenous peoples leading the way and helping us all to return to a more sustainable way of living on the planet. Don’t you agree?

I believe that the colonial mindset and systems that impose a sense of separation between humanity and the planet have indeed placed humanity on the path of premature extinction. However, Indigenous knowledges should not be idealized and consumed as a “quick fix” (see my answer to the above question). While Indigenous knowledges have significant contributions to make towards addressing the challenges we are facing, particularly in showing that a different form of existence is possible, it is unfair to put on Indigenous peoples the burden of solving all problems and being everything to everyone. I believe Indigenous knowledges and sensibilities (what Chief Ninawa Huni Kui calls advanced relational technologies) can support Western knowledge systems to recalibrate their orientation away from the current arrogance and alleged universalism and towards responsibility, respect, reciprocity, and reverence to the “environment” that we are part of. Instead of expecting Indigenous knowledge systems to replace or substitute Western knowledge systems, we should look at all knowledge systems as human constructs that belong to a dynamic “ecology of knowledges” (and ignorances) (Sousa Santos, 2007) where the contextual value of a knowledge system is measured based on its capacity to generate wisdom to secure the wellbeing of human and non-human beings for several incoming generations.

Some Indigenous individuals think that land acknowledgements are tokenistic and other Indigenous individuals and communities think they are important. What do you think?

Land acknowledgements and apologies in general have been recently criticized by Indigenous scholars and activists on the grounds that they tend to be tokenistic and deflect responsibility (Ambo & Beardall, 2023; Stewart-Ambo & Yang, 2021; Wark, 2021). It is like saying to Indigenous peoples: “I’m sorry for what we did to you, and thank you for the real estate!” My personal position is that land acknowledgements should be done in a way that acknowledges the historical and ongoing violence towards the land and towards the Indigenous people of the land. The land acknowledgement should also support the struggle and aspirations of Indigenous peoples to have their lands returned to them, as well as the wish of the lands to return to their people. I have recently started adding a sentence to the land acknowledgements that I offer to that effect: “I support the struggle of [Indigenous Nation or group] to have their lands returned to them and their livelihoods restored”.

Lost in translation

Should we replace the Western culture and systems with Indigenous cultures and systems?

Western political culture is primarily characterized by its focus on identifying exceptional and deserving leaders or groups to lead, with an overarching aim of replacing what is perceived as “bad” with what is considered “good.” I understand the appeal of wanting Indigenous cultures to fit the mold of exceptional and deserving leaders who can replace the bad with the good and I also understand how, for Indigenous Peoples, being seen in this way is way better than the usual deficit-theorization, pathologization, and racism. Therefore, many Indigenous individuals and groups will take the opportunities opened by this way of thinking and promise to deliver on these colonial expectations. However, replacing Western superiority with Indigenous superiority is problematic for many different reasons, including romanticization, but more importantly, because we are left with the problem of superiority. Superiority is the foundation of the colonial mindset, which also shows in the question itself. Indigenous political cultures are complex and diverse. They do not fit the Western mold. Attempting to fit select aspects of Indigenous cultures into colonial boxes to participate in the Western culture’s political arena offers short-term advantages for raising the profile of Indigenous cultures and individuals and long-term disadvantages for understanding the context of and building relationships with complex Indigenous Nations who live a reality that is different from what is often idealized.

How do/did Indigenous cultures perceive gender relations? Are/were they open to Two-Spirit people? Are/were they feminist?

Different Indigenous cultures have different perspectives on gender relations, reflecting the complexity of each society. These perspectives may also vary between generations due to the impact of residential schools on senior generations and the impact of modern culture on younger generations. Historically, some Indigenous societies recognized and respected individuals who embodied different gender qualities, including genders that today are sometimes identified as falling under the umbrella of “Two-Spirit,” as well as those who today identify as non-binary and/or trans. The concept of feminism, as it exists in Western contexts, did not have a direct parallel in traditional Indigenous cultures because the question of gender superiority (feminine or masculine or otherwise) was not what defined gender roles. Numerous societies practiced matrilineal kinship systems, wherein lineage is traced through the maternal line, a concept distinct from matriarchy, where women hold primary positions of power and authority, which is also practiced in some societies. Gender roles and views have changed over time, influenced by factors like colonization and cultural exchange, leading to a range of contemporary perspectives within Indigenous communities. Understanding these perspectives requires cultural sensitivity and recognition of the diversity and historical context of each culture.

What is the kinship worldview and why it is important?

The kinship worldview, which I refer to as inter-relationality, encompasses a profound understanding of interconnectedness and interdependence and the immense responsibilities that come with it. This inter-relationality binds everything together. What sets inter-relationality apart is its recognition that these connections are not static or one-dimensional; instead, they are characterized by a dynamic interplay of responsibilities, reciprocity, and accountability. It recognizes that actions must be considered within the broader context of how they affect the well-being of all beings involved. The importance of inter-relationality lies in its capacity to foster a profound sense of responsibility, humility, and stewardship. Viewing the world through this lens sheds light on how colonialism, which neglects these responsibilities, has harmed the life support systems essential for sustaining human existence and the existence of many other non-human beings. In reality there is not just one kinship worldview, but rather many diverse Indigenous communities that are organized according to different forms of kinship and (inter-)relationality.

Who can speak for Indigenous Peoples?

While each Indigenous individual can articulate their own perspective, speaking on behalf of Indigenous Nations and groups involves a more complicated dynamic. Various systems that confer authority for collective representation exist, such as hereditary leadership based on clans or families, with leadership titles passed down following distinct protocols. Additionally, colonial governments have imposed systems of elected leadership within colonially constructed structures. Spiritual leaders, Elders and experts in specific domains may also emerge as authoritative voices based on their experiences. When engaging with Indigenous voices, it is crucial to discern on whose behalf, under whose authority, and for whose benefit someone is speaking. For instance, I speak as an Indigenous individual and a member of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation, as well as an academic dedicated to a complexity-informed approach to Indigenous engagement and decolonization, representing my unique perspective within this complex landscape; I do not speak for or on behalf of my Nation, as I do not hold a leadership role within it.

Works Cited

Ahenakew, Cash. Towards scarring our collective soul wound. Musagetes Foundation (2019).

Ahenakew, Cash. “Grafting Indigenous ways of knowing onto non-Indigenous ways of being: The (underestimated) challenges of a decolonial imagination.” International review of qualitative research 9.3 (2016): 323-340.

Ambo, Theresa, and Theresa Rocha Beardall. “Performance or Progress? The Physical and Rhetorical Removal of Indigenous Peoples in Settler Land Acknowledgments at Land-Grab Universities.” American Educational Research Journal 60, no. 1 (2023): 103-140.

Andreotti, Vanessa, Cash Ahenakew, and Garrick Cooper. “Epistemological pluralism: Ethical and pedagogical challenges in higher education.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 7.1 (2011): 40-50.

Daigle, Michelle. “The spectacle of reconciliation: On (the) unsettling responsibilities to Indigenous peoples in the academy.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space37.4 (2019): 703-721.

de Oliveira, Vanessa Machado. Hospicing modernity: Facing humanity’s wrongs and the implications for social activism. North Atlantic Books, 2021.

Gaudry, Adam, and Danielle Lorenz. “Indigenization as inclusion, reconciliation, and decolonization: Navigating the different visions for indigenizing the Canadian Academy.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 14.3 (2018): 218-227.

Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures. “Letter to prospective immigrants to what is known as Canada” 2021. https://decolonialfutures.net/portfolio/letter-to-prospective-immigrants/

Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures. “Wanna be an ally?” 2019. https://decolonialfutures.net/portfolio/wanna-be-an-ally/

Jimmy, Elwood, and Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti. “Conspicuous consumption: economies of virtue and the commodification of Indigeneity.” Public 32.64 (2021): 121-133.

Jimmy, Elwood, Vanessa Andreotti, and Sharon Stein. “Towards braiding.” Musagetes Foundation (2019).

Reid, Andrea J., et al. ““Two‐Eyed Seeing”: An Indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management.” Fish and Fisheries 22.2 (2021): 243-261.

Stewart-Ambo, T., & Yang, K. W. (2021). Beyond land acknowledgment in settler institutions. Social Text, 39(1), 21-46.

Truth, and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Canada’s Residential Schools: The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015.

Tuck, Eve. “Suspending damage: A letter to communities.” Harvard educational review 79.3 (2009): 409-428.

Tuhiwai, Smith Linda. “Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples.” (1999).

Wark, Joe. “Land acknowledgements in the academy: Refusing the settler myth.” Curriculum Inquiry 51, no. 2 (2021): 191-209.

Whyte, Kyle. “Too late for Indigenous climate justice: Ecological and relational tipping points.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 11.1 (2020): e603.