Marketing the Object

Because books are necessarily either conceived in or born into material economic conditions, marketing considerations, whether conscious or not, play a large part in shaping a book: they underlie its production, play into aesthetics, and bridge the gap between author and consumer. Even if profit is not a primary incentive for producing a book, the cost of production means that those in the literary industry have to at least be aware of how their book will sell. With this idea in mind, a look at the physical form of the book can reveal consequences of such economic decisions. Things like the binding and cover style, paper quality, and size of the book can serve as evidence of a target audience that would desire and be able to afford the cost of a certain book.

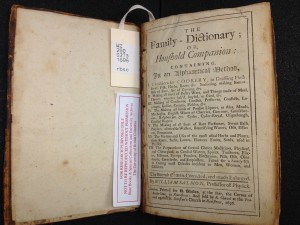

In the case of The Family Dictionary, I would surmise that its relatively cheap paper quality (browning and flaking with age, it is evident that the paper is of a fairly lightweight stock and has not held up well over time) and small size meant that the book was a fairly affordable object for its intended market of housewives and families (more on this below). An informative reference, its brown leather cover is conservatively, though not lavishly, decorative, exuding a quiet authority in its aesthetic appeal that defers to its purpose rather than exalting in its appearance.

Other books by William Salmon are similar in size and style; perhaps he produced them all with the same demographic in mind, or with the intention of his entire oeuvre occupying bookshelves side by side. Salmon, who lived from 1644 to 1713, wrote prolifically on the topics of medicine and herbal remedies, but also published texts on religion, drawing and painting, and astrology. The nature of the yet-to-be professionalized medical field at that time meant that the knowledge and skill set of medical practitioners varied wildly in both quality and credibility – the move to standardize and certify medical education and practice was largely a nineteenth century phenomenon. Home remedies were common and important sources of medical knowledge in the event that access to a doctor was unavailable.

The Title Page

One consequence of aesthetic features is their ability to visualize, sell, and generally represent the content of a work; the stakes of aesthetic choices resound upon closer examination of title pages and their purposes. Acting as a sort of secondary face to a book, title pages are valuable real estate for advertising a book’s contents, worth, and author. Indeed, the title page for The Family Dictionary features a methodical listing of its contents, author’s name and station (William Salmon, Professor of Physick), and printing and purchasing information. “London, Printed for H. Rhodes, at the Star, the Corner of Bride-lane, in Fleet-street : And sold by R. Clavel at the Peacock against St. Dunstan’s Church in Fleetstreet, 1696”, it announces. We are to be aware as well that this is the second edition of The Family Dictionary, differing from the original in that it is “Corrected, and much Enlarged”. (I will devote more attention to the editioning of The Family Dictionary below.) A casual encounter with a book more often that not includes the title page as one of the reader’s first impressions, so there is a strong incentive to make it a powerful one. Providing the details of where one might purchase the book also acts as a built-in advertisement for all parties involved in the book production and sale – more on this below as well.

The Preface

The Family Dictionary is aimed at, but not limited to “Ladies, Gentlewomen, and such other Persons, whose Station requires their taking care of the House”. Salmon also wishes to make clear that though he “seem[s] to inculcate that it is Addressed to Ladies and Gentlewomen, [he] would not be understood that it is fit for none else”. He discusses the relevance and utility of his book at length in the preface, noting that “[t]he Matters here treated of are very concise, yet plain, and possibly delivered in a Language not unpleasing to a Learned Ear; and may prove as useful to the more intelligent of Man-kind, as it can possibly be to those for whom it is more especially designed.”

In the preface we can see a cunning, if not altogether subtle, awareness of audience. Salmon very directly states the applicability of his work, simultaneously situating it in its imagined context and reinforcing its relevance. In a particularly self-aggrandizing passage, he writes,

“I shall say little to it, in the first respect; though I am satisfied it contains the best Receipts for Cookery that are Extant; and may serve the most delicate Palates, and Luxurious Minds, as a Treasury or Store-house, not only of Substantial and well made Dishes; but also of Picquant and Pleasant Sauces to stir up the Stomach, and provoke the Appetite.”

Throughout the preface, Salmon is careful to point out who should be interested in his book and why:

“Now as to the other part, which relates to Physick and Medicine, we have this to say, That though it contains not a vast Variety, yet it has enough of everything that is necessary, for any Gentleman’s Family; it is not stuffed with Impertinent, Impossible and Ridiculous Receipts; but furnished with the most Excellent and Profitable Medical Preparations for the Cure of most Diseases and Distempers usually befalling the Bodies of Men, Women and Children, and may stand in good stead, and serve in an Exigency, even when life lies at stake, or where an able and honest Physician is not near at Hand.”

We are also treated to a meditation on his own use of language – ironically, he discusses his supposed concision and utilitarian tone with a flamboyant and self-assured flourish:

“The Compositions and Preparations themselves, are delivered in few Words, not with Tautologies, and impertinent Digressions: The Expressions are Plain, the Language Easie, the Directions Obvious, and the Method Direct, for the Instruction of the Persons to whom it is intended, in the Performing and Compleating of all the things, herein contained, and which are indeed the most necessary and useful things, and the most desirable and profitable to humane Life.”

The preface ends with a particularly pointed guilt-trip-meets-religious-incentive, imbuing the purchase of his book with a holy grace and a moral exhortation:

“Lastly, It is addressed to Ladies, Gentlewomen, and Persons of Quality, to the Great, the Rich, the Noble, and the Generous Spirited, that they may do Good in their Generations, be helping and assisting to their Neighbors and Friends, and hold out a Hand of Relief and Comfort to the Poor, the Wretched and Miserable, whose Cries and Prayers will certainly call down the Bounties of Heaven upon you, and its Munificence perpetually to overshadow you, extorting from their very Souls a Blessing before they die.”

Notice how he includes “the Rich” in his list of people who could potentially commit a good deed by purchasing his book.

The Addition of Editions

The many editions and printings of The Family Dictionary is strong evidence of a positive, or, at least, a widespread, reception. Though the copy in UBC’s collection is a second edition work, the book went through four editions: the first appeared in 1695 and it was amended in 1696, 1705, and 1710. The purpose of a new edition can range anywhere from editorial to commercial: the choice to edition or re-edition a book is essentially one of packaging. Though new editions are often meant to correct their predecessors, they are often also advertised as having added, improved, or exclusive content, which can sometimes persuade those that have already purchased the previous edition that the new version is a necessary addition to their collection. A new edition can also be prompted by sales success and the necessity to reprint with some adjustment.

In comparing the first and second editions of The Family Dictionary, the most prominent difference can be found in the preface. In the first edition, William Salmon does not seem to target his book as precisely – perhaps he had not yet realized its sales potential in terms of a specific demographic, or had adjusted his focus subsequent to its success and an analysis of its market. Either way, the preface is addressed more gently to the “Courteous Reader”, emphasizes matters of health above all, and is “intended for the Publick Good”. Interesting to note as well is that Salmon’s full name is modestly absent from both the title page and the preface valediction in the first edition.

The third edition differs mainly in its length – it is expanded to include “several Hundreds of Excellent Receipts”. This trend continues into the fourth edition, which contains “above Eleven Hundred Additions, intersperst through the Whole WORK”. By this time, William Salmon has taken to including the official suffix “M.D.” after his name and has even included an extra title page proclaiming “SALMON’S Family Dictionary: OR, Houshold Companion” in huge, bold typeface. Clearly, Salmon realized and took advantage of every possible opportunity to advertise his qualifications and knowledge throughout his books.

Advertising

The front and back matter of the book made for very good advertising opportunities indeed. In some printings of the second edition, an advertisement for something called “Balsam de Chili” that could be purchased at the abode of William Salmon is included at the end of the preface. Hilariously, the fourth edition contains an advertisement in the same spot, though this one speaks to the clearly overwhelming amount of correspondence that the author has been receiving:

“I Request all those Gentlemen and others, who send Letters to me, about their own Concerns, to be so Civil, as to pay Postage for them; or else they may expect to go without an Answer. It is not reasonable that I should be at Charge for Persons, I have no Acquaintance withal, and the Business there own. I should not say this, was it but now and then a Letter. But to receive about Two Thousand Letters a Year, (as I have formerly done) upon other Peoples Affairs, or some Triffling Matters, and to pay Postage for them, makes a considerable Sum. And besides, it is as Burthensome and Troublesome to Answer them, as it is Chargeable to Receive them.”

The producer of the book also takes advantage of the back pages in each edition in order to advertise other books “[p]rinted for Hen. Rhodes at the Star, the corner of Bride-Lane in Fleetstreet”, conveniently noting the location where one might purchase them. The Family Dictionary has its own entry, suggesting either a very heavy-handed approach to advertising within the same book that is being sold, or, more likely, that this catalogue was a common feature of all the books sold by this producer.

As we have seen, examining aspects of literary marketing can lend insight into the persona of the author, illuminate the stakes of aesthetic dimensions, and provide a picture of the contemporary commercial scene. While some are convincing and others are downright transparent, marketing strategies are a key feature of book production and reception, and can allow us to see other conventional features of books in a new light.

learn more about:

the form | the author | the recipes | sources

or, go home