Humor Me for a Moment

Let’s talk about genre. So far, I’ve mentioned that The Family Dictionary is an alphabetically ordered domestic reference composed of both culinary recipes and home remedies. The side-by-side existence of these two categories may seem odd – what do they have in common, after all? Their ability to be made using ingredients and equipment from around the home? I’ve discussed here how home remedies were an important resource for those who were unable to access the help of a physician, but why would William Salmon have chosen to print culinary recipes alongside his medical instructions?

Perhaps we can better understand this decision by thinking about the way in which contemporary medicine framed the workings of the body. In Salmon’s time (and indeed, until well into the nineteenth century) one of the central paradigms in Western medical thought was humoral theory. The information on it to follow is a result of my consulting the Harvard Library’s Contagion project, a digital collection of historical material on disease and epidemics and a resource for concise introductory material on some of the general concepts represented within it.

Essentially, humoral theory conceived of the human body as a site of interaction between four different humors, which could be balanced to maintain an individual’s health. Since each person’s constitution was thought to be different, sickness and health were defined relative to an individual level of balance. The humors also categorized “four individual psychological temperaments: melancholic, sanguine, choleric, and phlegmatic”, reflecting “the humoral concept that physical health and individual personality were part of the same whole”.

Though to our eyes humoral theory probably seems wildly off the mark (it did, after all, advocate such practices as bloodletting and other bodily purging), some of the ways in which it framed the relationship between our bodies and the environment, and our health and our identities probably seem more familiar. These ideas are evidence of an understanding that we exist within a dynamic environment that can have an effect on our health, and that a great many factors play into the relationship between our choices and our bodies. Indeed, diet and lifestyle (as well as a great deal of other factors including climate, planetary alignment, sex, age, and class, to name a few) were thought to impact the equation of humoral balance; of course, we have evolved socially as well as medically, and hopefully now understand the problematic aspects of some of these assumptions. Now, as well as then, we are seeing the move towards medical treatments targeting the restoration of balance on an individual level while recognizing the body’s relationship to the rest of the environment.

With this in mind it becomes clearer why food and medicine share such close quarters in The Family Dictionary. To us, herbal concoctions probably seem to be a categorical middle ground, blurring the line between recipe and remedy. But we should remember that this categorization is itself a somewhat modern conceit; in Salmon’s time, this line was already blurred. Rather than distinct categories of things that would be ingested or prepared for different reasons, food and medicine would have been thought of as inhabiting the same spectrum of substances that had different properties, and therefore, different effects on the body’s humoral balance.

Culinary Ideology Then and Now

We live in an era of hyperconsciousness about health, embodied identity, and the triangulated relationship between our food, the environment, and ourselves. It is tempting to say, in the tradition of sensationalist media reportage, that we have never before been so obsessed with these ideas – indeed, bombarded with articles on exclusion diets, natural lifestyles, and empowering one’s identity, it can definitely seem like the paradigmatic tide is closing in on a new era of enlightened health and understanding about the body. But none of these are new ideas. Certainly, they have shifted, evolved, become hybridized and developed further with the support of both scientific and social movements, but there is nothing strictly modern about them – ideas do not develop in a vacuum, and they certainly do not emerge fully formed at the turn of a century or at the arbitrary delineation of an era.

Perhaps what I find most interesting about The Family Dictionary, and the reason why I decided to study it, is that it can tell us so much about the way that we think about bodies, identities, and social practices today at the same time that it lends insight about the way these ideas were handled in the past. As I hope to demonstrate by highlighting some of the recipe entries below, the text is embedded with contemporary assumptions about common knowledge and practice, and the way that the body was thought to relate to food and the environment; as such, it participates in a historical trajectory of both culinary and medical thought.

It is fascinating to trace commonalities (and even tentative ancestries) between trends in our current fields and their predecessors in this text published on the brink of the seventeenth century. This can provide us with context for these ideas, and perhaps in mulling them over in a new (or, in this case, old) light, we can reshape some of our assumptions about their relative importance or their attachment to certain ideologies. This can also illuminate some of the assumptions that we hold about our bodies, our environment, and ourselves, and underscore the values that are latent within them.

In other words, reading The Family Dictionary can enact a playful gestalt shift with our systems of values. After taking the time to relate to the ideas within it, it may not seem like such a window into the past – in fact, it may even act as a funhouse mirror, distorting and upending our preconceived notions about our collective cultural reflection.

Recipe Highlights

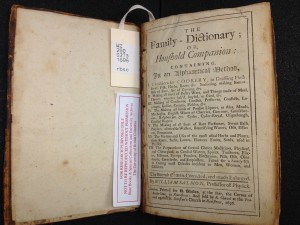

First, a bit of a glossary: when I first opened The Family Dictionary, I was greeted with its exceptionally long list of contents describing what its pages had to offer, some of whose terms were unfamiliar to me. Although by the seventeenth century the English language had developed into what we now recognize as Modern (as opposed to Old or Middle) English, some of the vocabulary and phrasing can still look somewhat antiquated to our twenty-first century eyes. Some of the decoding work that I did on the title page revealed these translations: chirurgical – surgical; usquebaugh – whiskey; metheglin – mead.

Looking up words while reading, I began to tumble down the rabbit hole of British culinary history. Wikipedia articles and bloggers ranging from the interested amateur to the seasoned scholar have much to say and show from their pursuits into historical cuisine – often, they skillfully reproduce the dishes in question to demonstrate the trove of inspiration that is our gustatory past. (I have included a list of further reading on my sources page.) These words and techniques can seem anywhere from quaint to intimidating at first, but they do start to resemble more familiar territory given some research, thought, and even reenactment.

I encountered a rather amusing example of shifting terminology (at least, to my mature and sophisticated sense of humour) in the first section of the book. Apricots, as we currently know them, used to be called Apricocks; here is what William Salmon has to say about them:

“Apricocks are a delicious Fruit to the Taste, and much more wholsom than the Peach; but above all, from the Kernels of them an excellent Oil is extracted by expression; which being mix’d with two part of Oil of Amber, is excellent for Hemorrhoids, Pains in the Ears, Swellings and Inflammations.”

Another small stumbling block that I encountered in my reading was the imprecision of the instructions. Getting inspired by the simplicity of the recipes that used familiar ingredients in ways that were (to me) new and beautiful, I mentally went through the processes outlined in the text. But I realized that I had so many questions about them – what temperature to bake something at? What quantity of ingredients to use? How long would this take me? These questions were totally unaddressed in the short, crisp prose of the recipe entries.

Perhaps the phrase that best illustrates this ambiguity is one in the recipe for “Salmon Frigassed” (or “Fricasseed”, to our modern vocabulary):

“Take a Piece of fresh Salmon, and cut it into the length or thickness of your fore Finger; then take some sweet Herbs with Parsly, and a little Fennel; and mince them very small; then take some Salt, Mace, Nutmeg, Ginger, Cloves, all beaten together, and put them to your Salmon, with the Yolks of half a score Eggs, and mix them very well together, in the mean time get your Pan in readiness full of clarified Stuff and very hot, then with all the quickness you can, scatter your Fish with its Appurtenances, be sure you keep it from frying in Lumps; when it is three quarters fryed, pour away your Liquor from it, and in its room put in some Oister Liquor, some White-Wine, some large Oisters, Two Anchoves, a large Onion, Nutmeg and minced Thyme; being ready, dish it, and pour thereon the Yolks of four Eggs, beaten with some of the aforesaid Liquor, and run it over with drawn Butter, garnish it with Oysters, and serve it up on Sippets.”

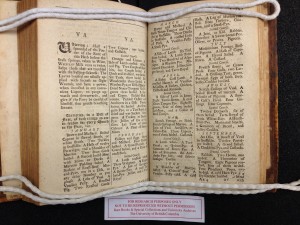

Pages 296-297 of The Family Dictionary; the recipe for “Salmon Frigassed” can be seen starting in the bottom left-hand column of the right facing page.

Ironically, the phrase “clarified Stuff” could not be more unclear to me. I had to look up what “sippets” are (small pieces of dried toast or fried bread, similar to croutons), and shuddered at the euphemistic use of the word “Appurtenances”. In thinking about all the things I had difficulty interpreting, I meditated on the genre of recipe language more broadly. Relying simultaneously on precision and concision, inherent in most recipe directions is a certain amount of knowledge that a cook should already have. For instance, recipes that involve boiling water generally do not bother to unpack the process in any great detail; they assume this knowledge on the part of the cook and carry on from there. As such, my gut instinct is to attribute my confusion at the directions in The Family Dictionary to a lack of the kind of common knowledge that a contemporary reader would have possessed.

Imagine that you had to write down the instructions to a recipe you knew off by heart – how many small details would you forget to include, or take for granted as obvious? The gaps in our understanding as we look back on these antiquated instructions can illuminate some of the interstitial assumptions that were carried within the practices of everyday life in this time period – for instance, regarding the type of standard equipment one was likely to have on hand, or the processes that would or would not have warranted a more detailed explanation.

This ambiguity also points to a development in the history of the recipe genre – it was only in the mid-twentieth century that the exacting standards of the test-kitchen mentality began to be imposed on our culinary instruction. Before this trend was to come to fruition, recipes largely existed as mnemonic reminders of processes or practices that were also stored in muscle memory. Even now, the precision we demand from our recipes co-exists with the understanding that learning to cook necessarily involves an embodied, practical element. Hence, the measurement of a piece of salmon with “the length or thickness or your fore Finger”, highlighting the hands-on dimension to the culinary experience.

The Family Dictionary does not leave us entirely to guesswork, however. Salmon does have several sections in his book that explain some of the more esoteric terminology he uses. In the medical realm, we have his “Terms of Art, and Hard Words in Physick, &c. Explained”:

“Abstergent, wiping.

Acrimony, is a Quality that is biting upon the Tongue.

Acid, is a thing very sharp, viz. Liquids, Herbs, &c.

Agglutinate, to glue together.

Alexipharmick, resisting Poison.

Alternately, by Turns.

Anodyne, gives ease.

Aperitive, opening.

Aqueous, watry.

Aromatick, odiferous, or Spicy smells.

Asthma, Difficulty of Breath.

Attenuate, to thin.

Attractive, Drawing.

Astringent, Binding.”

So reads the “A” section; perhaps the entry as a whole can supplement our understanding, though it is still reliant on a contemporary common vocabulary and sensibility. This entry is followed by an oddly rhythmic list, “Terms of Carving”, which reads like a terrifying biblical nursery rhyme of violent actions that one can perform on various game meats:

“Leach that Brawn. Break that Deer. Lift that Swan. Break that Goose. Sauce that Capon. Spoil that Hen. Frust that Chicken. Unbrace that Mallard. Unlace that Coney. Dismember that Hern. Disfigure that Peacock. Display that Crane. Untach that Curlew. Unjoint that Bittern. Allay that Pheasant. Wing that Quail. Mince that Plover. Wing that Partridge. Thigh that Pigeon. Border that Pasty. Thigh that Woodcock. And the Word in carving proper to all manner of Small Birds is to Thigh them.”

This is followed by a further explanation of how to enact each of these actions; for example:

“To Dismember a Hern: Having taken off both the Legs, lace it down the Breast with your Knife, and raise up the Flesh; then take it quite off with the Pinnion and so stick the Head in the Breast, and set the Pinnions on the contrary side of the Carcass, and the Legs on the other side, so that the Ends of the Bones may meet across over it, and the other Wings cross over the top of it.”

The technicality of this process is hard to demonstrate without a visual aid; it stands in stark contrast to the straightforward diagrammatic illustration of a modern publication like Cook’s Illustrated (one of the bastions of the test-kitchen mentality). One thing that I found oddly familiar, however, was an entry titled “Varieties, in a Bill of Fare, of such things as are in season for every Month in the Year”. Seasonal eating has become a trendy feature in the realms of fine cuisine, personal eco-consciousness, and the broad category of “lifestyle” publications. Touted for its sustainability and its emphasis on our place and participation in a larger ecosystem, seasonal eating is one current focus of the “back-to-the-earth” ethos affirmed by our present-day media and everyday practices.

William Salmon demonstrates, however, that there is nothing novel about this idea; in fact, before the vast networks of trade that we currently enjoy were established to the same degree, it was a necessity (rather than a hip, eco-conscious phenomenon) to eat seasonally, especially in a small island country like Britain. As an example, here is what he suggests for the month of June:

“A Shoulder of Mutton hafh’d. A Chine of Beef. A Venison. Pasty cold. A cold Hash. A Leg of Mutton roasted. Four Turkeys, Chickens, and a Steak-Pye.

Second Course.

A Jane, or Kid. Rabbits. Shovelers. A Sweet-bread-Pye. Olives, or Pewits. Pigeons.”

Like his recipes, his menu planning is short and to the point, and is probably meant to be a shorthand for dishes that would immediately come to mind in stating their constituent ingredients. Additionally, the idea of eating in season may have also resonated with the belief in balancing one’s humors against the changing climate and temperature of each time of the year.

I’d like to conclude my examination of recipes with another entry that falls into the category of “lifestyle advice”. One current media phenomenon I’ve been noticing to great extent is the collection of news articles that fixate on life advice from centenarians. The preservation of youth has always been a cultural fixation (at least, in Western thought) in material ranging from fairytales to women’s magazines, but apparently William Salmon had something to say on the topic as well. Here is the very last entry in The Family Dictionary:

“Youth to Preserve: This is chiefly done by a careful Observation of Diet, and a good Course of Living. 1. Use moderate Exercise, to keep up the native heat, and the Humours and Juices from Stagnation. 2. Beware of Drinking to Excess, or using hot and Spirituous Liquors, as strong Drink, Wine, &c. too liberally, or too often, for they destroy the Tone of the Stomach, and bring unaccountable Disorders upon the Body. 3. Eat moderately, and such things as the Stomach does easily digest; twice a day is enough for such as are not Labouring Men. 4. Use perpetual change of Diet, and eat not two days of the same kind of Food, for the Stomach, as well as Nature requires Variety, and thus you may go the rounds with all things Eatable. 5. Let all your Meats be drest rare, and not too much done; for if their Juices be once out of them, the Stomach is not pleased with them, nor does it easily digest them; and Experience daily testifies that such as from their Infancy up, have eaten their Meat so drest, as to have all their Juices in it, look younger at Threescore and ten, then others who constantly eat them so over done, do at Twenty five Years old, or thirty, and this is the reason that Jews and French Men and Women, who eat all their Food so over drest, look even whilst young, so Yellow, Dry, Wrinkled, and as it were Withered, that an old English Man or Woman look better than they, and in Age look extream hagged, beyond all manner of Expression. 6. By eating moderately strong Broths, and Jellies, and the red Gravy of roast or boiled Meats. 7. By taking now and then the Powers of Vipers in Wine, or the Viper Pouder, and moderately drinking Viper Wine, only for Strength sake.”

So there you have it. William Salmon’s strongly worded and occasionally uncomfortable opinion on the question of lifestyle, with all its contemporary cultural, medical, and gendered assumptions intact. This is not to suggest that this entry functions as a seamless metonymic representation of these ideas at the time; only by reading an array of material and putting it in an equally complex context would we come to possess a fluency in the conventions and ideas of the past. However, what I hope to have demonstrated here are the different ways in which people now, as well as in Salmon’s time, come to be convinced of different ideas about their bodies, their health, their identities, and the way that these participate in the complex and holistic constellation that we call a lifestyle.

learn more about:

the form | the book market | the author | sources

or, go home