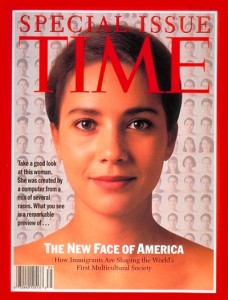

Yesterday’s discussion in class on race, ‘imagined citizenry’, and identity caused me to think about my own identification with culture. I was born in the United Kingdom and immigrated to Australia at the age of 9. At the age of 15, my family and I received official Australian citizenship. Given my young age when we moved to Australia, my twin brother and I were susceptible to the Australian accent and thus by the time we finished elementary school people could no longer tell that we were English.

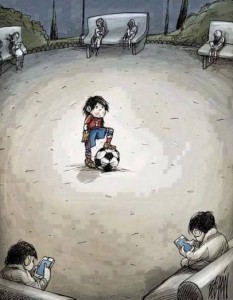

When we first arrived in Australia, my brother was given the nickname ‘pommy’ by his Australia mates. Pommy being derived from the word Pome meaning ‘Prisoner of Mother England.’ He did not take offense to the title (probably glad just to have made friends so quickly!), but I’ve seen this term used on other English friends and even my Dad, who have been offended by its meaning.

As I’ve travelled around the world and met new people, I’ve found this dual citizenship that I have to be a point of disequilibrium of my identity and culture. My parents who lived in the UK for over 40 years introduce themselves to people as English. Yet, given that I have now lived the majority of my life in Australia, I never really know what to say when people ask ‘where are you from?’

When I say I’m English, people respond with ‘but no you’re not… you have an Australian accent and you live in Australia?’ And it takes me a moment to think, yeah they’re right aren’t they?

I grew up in the United Kingdom in a tiny village: think 1 school, 1 pub, 1 shop, 1 park. Our house was surrounded each way by acres and acres of farmland belonging to local farmers. Christmas time meant snowmen, school being cancelled and nights by the fire. Despite the UK and Australia being very similar, Anglo-western countries, the culture and experiences I grew up with are far different than to that of my Australia friends.

I am a white woman. My identification with the United Kingdom and with Australia is not markedly different from the expectation of my visibility and appearance. Towards the end of yesterday’s class we talked about ‘appropriating culture’ and the problems that arise with the consumption of other bodies and other cultures. I echoed the thoughts of others in the class who held the view that one should not teach or advocate for a culture if they are not part of it. It is crucial to acknowledge the infrastructures of power and privilege to place yourself within a marginalised culture or group of people and in the discussion of the oppressions they face.

-Aimee