Let me begin by stating that this piece is not in support of Abbott’s decision regarding AusAID. His intentions were clear; he simply does not see development aid as a priority relative to other portfolios. If he did, he would have used the opportunity to acknowledge that the current system is not working and to find ways to make it more effective.

Rather then focusing on Abbott’s decision, this blog aims to cut through the polarising nature of the debate to encourage improvements to our current development funding processes.

—————————————

Less than 48 hours out from the Australian Federal Election this year, the conservative Opposition announced that they planned to slash the growth rate of foreign aid spending by $4.5billion over four years. Two days later, this same party won the election, ascending Tony Abbott to the seat of Prime Minister of Australia.

The announcement of foreign aid cuts triggered backlash and anger through many sects of Australian communities. In addition to his cries to “stop the boats”, Prime Minister Abbott emblazoned himself as an infrastructure leader who would “put bulldozers on the ground and cranes into our skies”. Disgruntled Former Foreign Affairs Minister, Bob Carr, declared that Australian aid spending (0.37 per cent of national income) was “in our interests” and that “Australian security is served by an effectively delivered foreign aid program” (Australian Network News, 2013). Were we putting ourselves at risk by reducing our foreign aid balance?

Abbott’s move to direct funding towards infrastructure for Australian cities and Carr’s subsequent comments got me thinking more broadly about why Government’s around the world fund foreign aid and if the model is successful for those it intends to aid. Julie Bishop, the new Foreign Minister, made her first major statement on aid in November 2013 that AusAID was being abolished and its functions merged with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. It is being returned to the foreign ministry, with Abbott citing a need for greater alignment between “the aid and diplomatic arms of Australia’s international policy agenda”. Strategic intent is claimed to be at the centre of government funding of aid, with foreign aid programs “always bedeviled by conflicting national foreign policy objectives” (Creighton, 2013).

Is aid purely strategically pragmatic, fueled by emblazoned security concerns? Is it merely a way of privileged nations to symbol their wealth or ascend their guilt? If aid is designed with such notions in mind, how can the resulting programs that they fund be effective, transparent, impactful and responsive to the real needs and voices of often-distant communities?

—————————————

The aim of this piece is not to take a side on whether government aid funding cuts are right or wrong, rather the objective is to show the importance of asking the right questions before condemning an action. My initial response to Abbott’s announcement, following a brief squirm of resentment, was the desire to understand the current effectiveness of aid that is funded by the Australian Government. If the current program of aid is not – for lack of a better word – aiding developing communities, why should it continue to grow?

Exclusively measuring the amount of money delivered to such programs is, in my mind, a very rudimentary way of evaluating the effectiveness of aid. Following my coursework focused upon the Monitoring and Evaluation of Timely Responses (METR) for development, I find evaluations of aid that focus purely on inputs and outputs, with no attention given to the intended and unintended impacts of programs, negligible. We should be asking what the intended impact is, the long-term objective, and if the billions of dollars that go into development aid are effective against them. Are we wasting our aid dollars on programs that aren’t working?

—————————————

AusAID was tasked with a complex undertaking. An Audit Report of AusAID’s management of the expanding aid program (2010) stated that the scaling up of Australian aid and the impetus to change how aid is delivered amplified key challenges. A key finding of the audit was that continued improvement in the monitoring and evaluation of aid is required to if AusAID is to remain in a good position to meet the challenges of the coming years (ANAO Audit Report, 2010).

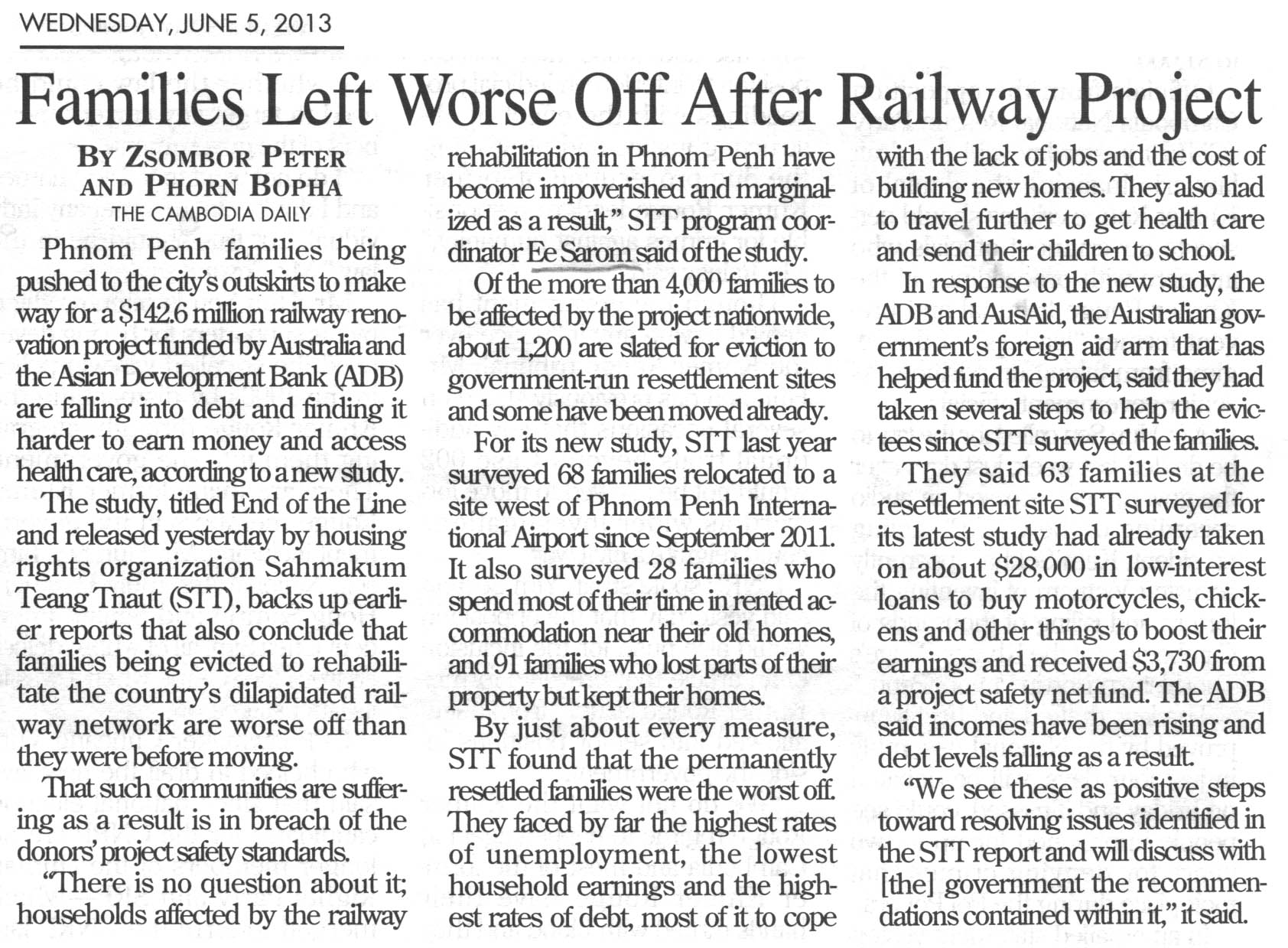

For every example of a successful development program, I can only guess the disproportionally high degree of failures. An article focused on AusAID’s failure of commitment to human rights in Cambodia (Macdonald, 2013) is one such example. The article opens in a poignant manner with the author openly stating that a Cambodian infrastructure development project has resulted in the displacement and violation of people’s land rights. He notes that this may not be surprising in a country that is recognised for its entrenched poverty, financial opportunism and government heavy handedness. What is surprising, however, he notes, is when these projects are “financed and managed by the organisation’s whose stated purposes are to work to improve the lives of world’s poorest and most vulnerable” (MacDonald, 2013).

AusAID provides 15 per cent of the financing for the Railway Rehabilitation Project in Cambodia as part of its “Australian-Cambodia Joint Aid Program Strategy 2010-2015”. A project that aimed to link Cambodians with each other and with external markets has been plagued by inadequate consultation, compensation and displacement of local people. Those relocated have inadequate access to basic services and employment. A report published by Aid/Watch notes that the obsession with ‘economic development’, over human development, including the privatization agenda, are specifically troubling – “the project has been unable to articulate in any way how it will effectively reduce poverty” (AidWatch, 2012). Although AusAID may have had good intentions in entering the Cambodian project, such intentions are inadequate, and “ignorance is cold comfort to the people whose lives have been destroyed” (AidWatch, 2012).

This example is only one of many of the projects that Australian aid has funded that are in line with our ‘strategic interests’. Although I do not condone the actions of Abbott in cutting the budget, I do embolden our leaders to implement transparent and accountable monitoring and evaluation procedures that are context-specific and put the beneficiary at the heart of the development agenda. I acknowledge that measuring the effectiveness of development aid is inherently complex and difficult, particularly when there exists uncertainties about intended objectives and the isolation of causal effects. But, that is not an excuse to only measure those hard and fast indicators that are ‘easy’, such as dollars spent or programs funded. Let’s begin by assessing the intervention logic, the design of the program itself and it’s relevance. What are the intended and unintended benefits and costs of the project to the multiple stakeholder groups?

—————————————

Let us rethink how to more appropriately spend development aid by monitoring and evaluating projects in a timely manner and by asking the tougher questions. If Abbott invests money in an independent evaluation house to do so, he will have my attention. Slashing the budget in itself is not a helpful solution to the problem of aid not being effective.