What is the Southern Bluefin Tuna?

The Southern Bluefin is a highly migratory, fast swimming fish that live in open seas. As a result they support several international fisheries.

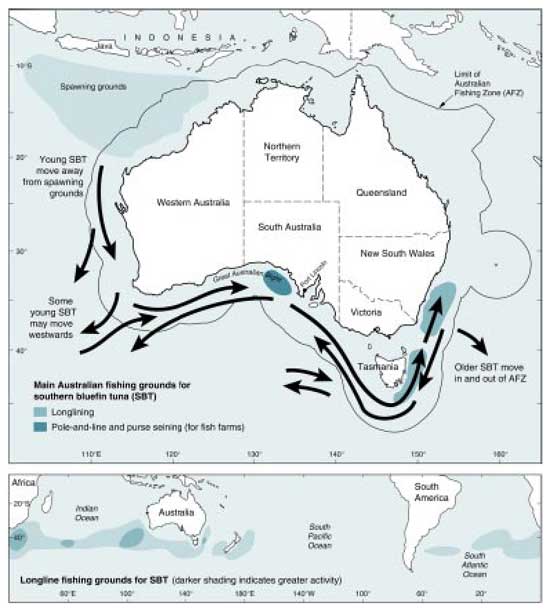

They begin their life in warmer water in spawning grounds between Australia and Java. From there, juvenile fish leave the spawning grounds, and move south during summer along the Western Australian coastline towards the Great Australian Bight. They also travel west towards South Africa through the Indian Ocean (Welburn, 2011, Mori, Katsukawa et al, 2001).

The Southern Bluefin Tuna are fished by high seas long-line vessels and purse seine. Upon catching (between 13 and 25kg), the fish are towed back alive to “static growth pontoons” off Port Lincoln in South Australia. After six months of being grown out, they are harvested and exported, mainly to Japan (AFMA). The overwhelming majority of the fish is sold in the Japanese sashimi market (The Conversation, 2013).

The problem

Southern Bluefin Tuna have historically been heavily fished since the 1950s, which has resulted in decline of mature fish as well as annual catch falls. The over-fishing has been to levels that are above the average maximum sustainable yield.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has a ‘red list’ that categorizes species according to their vulnerability of extinction (Welburn, 2011). The Southern Bluefin tuna has been red listed as a ‘critically endangered species’ due to its rapid decline in quantity (Punt, 2008, in Welburn).

Policy reaction

A voluntary mechanism to limit catch was introduced by Australia, NZ and Japan from 1985. In 1993, there was a move to a more formal management mechanism, with the creation of the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (hereafter CCCBST), headquartered in Canberra.

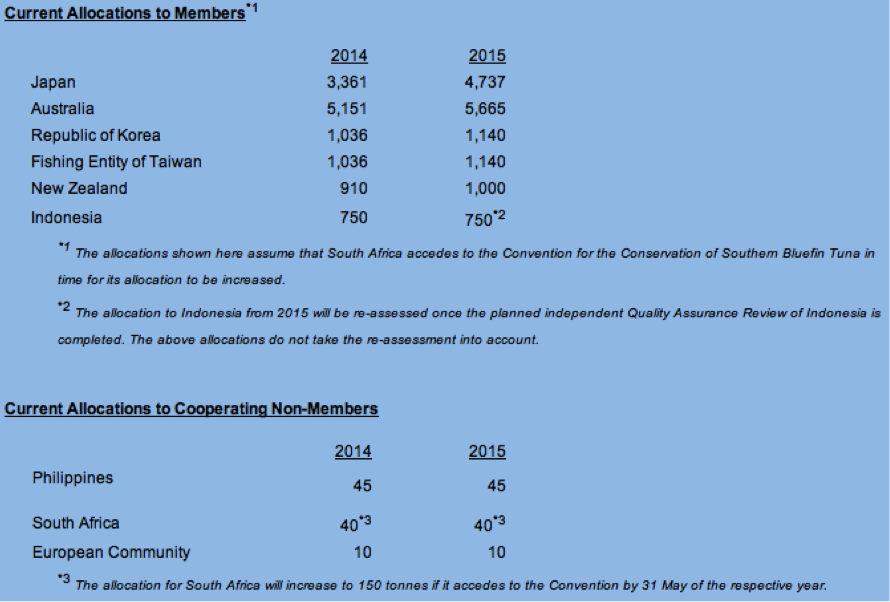

The Republic of Korea, Indonesia and Taiwan joined the original three in 2001, 2008 and 2002 respectively and the Philippines, South Africa and the European Community were formally accepted as “Cooperating Non-Members in 2004, 2006 and 2006 respectively (CCSBT).

Policy mechanism

Catch for the Southern Bluefin Tuna is regulated via two mechanisms, a global total allowable catch (TAC) as well as individual country-specific transferable quotas (ITQ) set by the CCSBT.

In Australia, the ITQs are allocated as Statutory Fishing Rights. The Australian Fisheries Management Authority (hereafter AFMA) determines a TAC for the Australian domestic fishery, which is based on the allocation from the CCSBT. A Statutory Fishing Right then entitles the holder to receive an equal portion of the TAC set by the AFMA (AFMA, 2012).

A formal rebuilding management regime was adopted in 2011 in response to significant under-reporting discovered. The 2011 management procedure (harvest strategy) aimed to guide recovery of biological stock to 20% of unfinished biomass by 2035 (FRDC, 2012).

The “management procedure” provided guidance for the CCSBT to set global TAC as well as to provide the “fishing industry with stability in the level of catch over a set period of time” (DAFF, 2012). The TAC can be updated based on monitoring data, according to the following parameters:

- set for three-year periods

- built on a 70% probability of rebuilding the stock to the interim target point of 20% of the original spawning stock biomass by 2035

- the minimum TAC change is 100 tonnes

- the maximum TAC change is 3,000 tonnes.

The FRDC reported that the CCBST set the global TAC for 9,449t (2010), of which Australia had the largest quota of 5,265t (2010). The Australian Fisheries Management Authority reported that approximately 96% of Australia’s quota is caught by five purse seine vessels.

Monitoring and surveillance

The CCSBT has several monitoring, control and surveillance schemes including:

- Catch Documentation Scheme (2010): tracks and validates legitimate flow from catch to point of sale on domestic or export markets

- Monitoring of SBT Trans-shipments at Sea (2009): applied to long-line vessels with freezing capacity.

- Approved Vessels and Farms: not allowed to land or trade SBT caught by those not on the list

- List of Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing Activities (2013): identify vessels engaging in IUU each year

- Vessel Monitoring (2008): Members and co-operating non-members required to adopt and implement satellite vessel monitoring systems.

- Action plan: to build cooperation in supporting management and conservation measures. CCBST has advised if cooperation is not forthcoming, measures including trade restrictive measures, may be taken against them.

A separate by-catch and discards work-plan has also been developed (AFMA). In relation to boat numbers, although the number of active global vessels catching SBT is not available, the most recent estimates cite approximately 1,296 vessels in 2010 (FRDC, 2012). In Australia in 2010, six purse-seine vessels and 18 long-line vessels caught SBT (FRDC, 2012).

Potential advantages and disadvantages

1) TAC size

The most recent figures for 2011/12 provided by the AFMA, recorded:

- Agreed Australian TAC: 4,528t

- Reduced TACL 4,509t (because overfished in previous year)

- Catch: 4,543t

- GVP: $40,503,000

- Farm gate value: AU$150million

The catch of 4,543t can be compared to a 21,000t TAC, which was implemented, but not binding, by the Australian government in 1983 (Coombs, 1997). This represents major progress in responding to the reduced Southern Bluefin stock. In addition, the TAC can contract and expand, which produces an incentive to increase the overall stock to increase individual share.

However, is it enough? As discussed above, quotas are set for three years to provide stability for fisherman. They can also increase, which they have, which has brought fierce criticism from environmental groups. Greenpeace (2013) slammed the three consecutive years of increase in quotas and called for “zero catch” as “the only way to ensure survival of a species decimated by overfishing”.

“The Southern Bluefin fishery has been a case study in mismanagement and this new announcement continues to play Russian roulette with the survival of an entire species.”

Nathaniel Pelle, Greenpeace Oceans Campaigner

“Current stock assessments show that this is already a fishery in collapse. The simple truth is we need to leave the Southern Bluefin tuna well alone for a while so that stocks can recover as quickly as possible.”

Pam Allen, Australian Marine Conservation Society campaigner

2) Suitability of ITQs: price and fleet response

The use of ITQs suits Southern Bluefin fisheries for a number of reasons, as outlined by Coombs (1997):

- They are a long-lived species with small annual variations in parental stocks

- Market outlets were relatively few and well defined, which may reduce black market sales and the costs of enforcement.

In response to early ITQ’s, the average price of Southern Bluefin Tuna increased by more than double. In addition, Coombs (1997) reported that the system allowed Australian fisher’s to maximize the value of their catches “by concentrating on larger fish rather than maximizing the total amount of their catch (as is the incentive with aggregate quota schemes).

The ITQ changed the structure of the Australia fleet as fishermen had two choices: sell quota and exit the market, or buy additional quota. Many New South Wales and Western Australian fishermen exited the market and those remaining purchased additional quota and subsequently had to increase the scale of their respective operations (Coombs, 1997). However, as Coombs (1997) explained, although the ITQ reduced the amount of Southern Bluefin caught and increased efficiency of the fleet, they did not succeed in restoring parental biomass to desired levels.

3) Global agreement

For a highly migratory species, it is difficult to enforce global participation to reduce overfishing. The Southern Bluefin Tuna TAC has been an example of international cooperation and enforcement.

However, it is also due to the global nature of the system that causes problems. The Conversation (2013) argued that there is often decision paralysis and status quo management because management is via international agreements on quotas. They noted that this management system “can be slow to respond to problems such as low numbers, leaving the population ill-equipped to deal with the vagaries of juvenile survival” (The Conversation, 2013).

4) Illegal fishing

As discussed above, there is significant enforcement and monitoring in place, that far outstrips many other fish policy initiatives. However, IIU continues to be an issue with reports of declines in mean lengths of Southern Bluefin in spawning grounds. This has been an indicator of Indonesian vessels fishing below the spawning grounds south (AFMA, 2013) and the issue is currently being investigated further.

Current state

The Conversation (2013) reported that the current best scientific advice is that mature biomass is between 3-8% of the tuna’s un-fished level. This is well below sustainable levels. Supporting this, the stock assessment completed by the CCSBT in 2011 suggested that the spawning biomass is well below the level that could produce maximum sustainable yield (AFMA). The FRDC (2012) reported that measureable improvements in spawning stock are yet to be detected and the stock status remains “OVERFISHED”.

However, the AFMA reported that there is a positive outlook for stock based on the 2011 assessment, which include a continued reduction in total reported global catch. In addition, the current mortality has reduced below Fmsy (maximum rate of fishing mortality: proportion of fish stock caught and removed by fishing) and stock is expected to increase at current catch levels (AFMA, 2012).

References

Australian Fisheries Management Authority (2012), ‘SBTF at a glance’, Available online at http://www.afma.gov.au/managing-our-fisheries/fisheries-a-to-z-index/southern-bluefin-tuna/at-a-glance/

Commission for the Conversation of Southern Bluefin Tuna, ‘Origins of the Convention’, Available online at http://www.ccsbt.org/site/about_commission.php

Coombs, J., (1997), ‘ Individual Transferable Quotas in Fisheries’, Available online at http://personal.colby.edu/personal/t/thtieten/itqs-aus.html

Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, (2012), ‘Commission for the Conversation of Southern Bluefin Tuna’, Available online at http://www.daff.gov.au/fisheries/international/ccsbt

Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, (2012), ‘Southern Bluefin Tuna’, Available online at http://www.fish.gov.au/reports/finfish/tuna_and_billfish/Pages/southern_bluefin_tuna.aspx

Greenpeace Australia Pacific, (2013), ‘Increased quotas will decimate critically endangered southern Bluefin tuna’, Available online at http://www.greenpeace.org/australia/en/mediacentre/media-releases/oceans/Increased-quotas-will-decimate-critically-endangered-southern-bluefin-tuna—Environment-groups-call-for-zero-catch-4/

The Conversation, (2013), ‘Australian endangered species: Southern Bluefin Tuna’, Available online at http://theconversation.com/australian-endangered-species-southern-bluefin-tuna-11636

Welburn, N., (2011), ‘Reversing the decline of the Southern Bluefin Tuna. Are Marine Protected Areas the Answer?’, Bangor University. Available online at https://www.academia.edu/2343330/Reversing_the_decline_of_the_southern_bluefin_tuna._Are_marine_protected_areas_the_answer