The In’s and Out’s of Australia’s Carbon Policy

<<This post was created as part of a course requirement for ‘Environmental Economics and Policy’ >>

Carbon policy is inherently complex, uncertain and highly political. Australia is no exception to the case, and may in fact have taken it to another level completely, being the first nation to abolish a carbon tax after only one year in administration.

‘It’s official, Australia has a carbon tax’ (The Australian, November 08, 2011)

…but less than two years later…

‘Tony Abbott locks in death of carbon tax’ (The Australian, August 16, 2013)

In September 2013, Australia heralded in their 28th Prime Minister, Coalition Leader Tony Abbott. Upon winning the Federal election convincingly, Abbott’s first order of business, as promised, was to repeal the Carbon Tax. The Coalition had built their election platform on the disbandment of the Clean Energy Act 2011 in favour of a ‘Direct Action Plan’, which looks to incentivize industry directly to reduce emissions. Thus, whilst many countries are working to introduce, iron out and implement carbon taxes, Abbott is committed to push through legislation to dismantle ours.

So what is it that Abbott is repealing? It is important to first understand our current Carbon Policy, its coverage as well as distributional effects. We can then begin to compare Australia’s policy to the rest of the world, as well as to the ‘Direct Action Plan’ that Abbott is suggesting to replace it.

Clean Energy Act 2011

In 2011, a package of carbon pricing bills was passed through the House of Representatives. The central tenet of the act, the Carbon Pricing Mechanism (CPM), which took effect on July 2012, introduced an emissions trading scheme that put a price on Australia’s carbon emissions.

Julia Gillard, Labour Prime Minister, coined the term ‘carbon pricing mechanism’ when communicating the party’s carbon policy. This was in response to several announcements as part of her winning election platform where she promised she would not introduce a ‘carbon tax’. However, many have argued that there was no practical difference between a fixed carbon price and a carbon tax, as they both drive up the cost of energy to bring about a reduction in energy use (Professor Michael Dirkis, ABC, 2014). The label of the policy became a point of contention and Gillard was consistently caught up in definitional debates. Gillard admitted recently that “her decision not to argue against a fixed carbon price being labelled a “tax” hurt her terribly politically” (ABC, 2014).

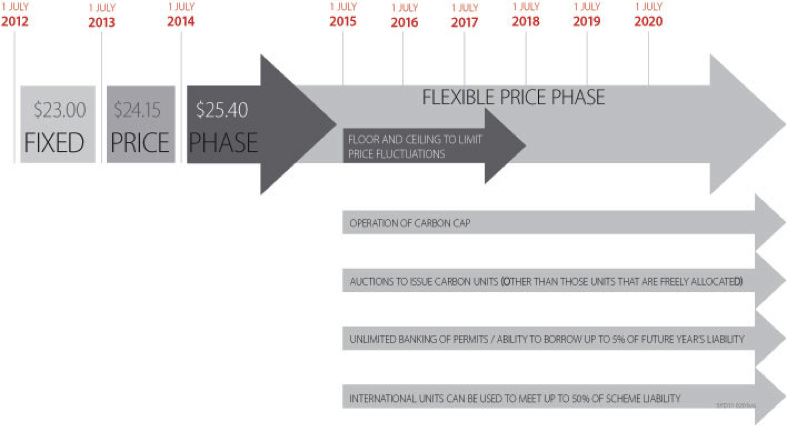

The CPM was to be introduced in two phases, with a fixed phase, beginning in 2012 to be following by a flexible price in 2015. Initially, the price of carbon units would be $AUD23.00 (2012), $AUD24.15 (2013), and $25.40 (2014), with a floor price of $15.00. During this period, there was to be no limit on the amount of permits able to be purchased. The second phase was to be characterized by a cap-and-trade system, where the Government would set caps on the number of units to be issued each year (Minter Ellison, 2012). Supply and demand forces would interact to determine the price paid for available carbon permits.

Coverage

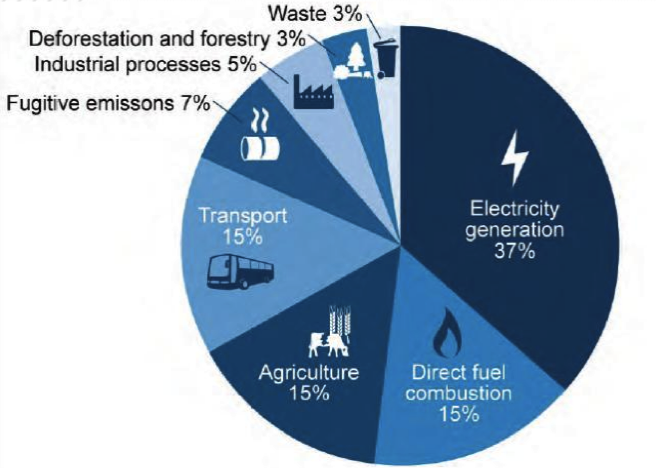

In 2011, Australia’s emissions profile looked something like this:

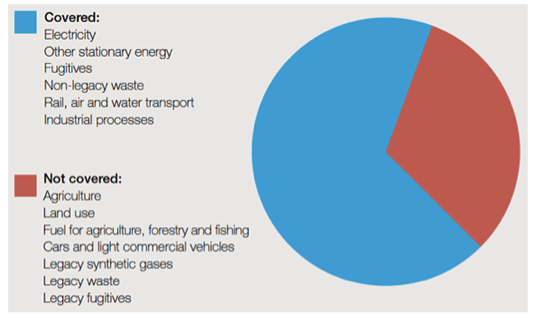

So who was in and who was out? In regards to coverage, Australia’s Clean Energy Regulator (2014) stated:

“Generally, if a facility meets or exceeds the threshold of covered emissions with a carbon dioxide equivalence (CO2-e) of 25 000 tonnes in a financial year, the person responsible for such a facility will be liable under the carbon pricing mechanism”.

However, not all of the sectors in the chart above were covered as part of the carbon tax threshold. Those industries covered (if above the annual threshold) included:

- Stationary energy (e.g. Electricity generation)

- Industrial Processing (e.g. Aluminum smelting)

- Fugitive Emissions (other than from decommissioned coal mines) (e.g. Emissions from extraction of coal, oil and natural gas)

- Emissions from landfill waste and waste water treatment (legacy waste exempted).

Emissions not covered by the CPM were:

- Agriculture

- Land use, land use change and forestry

- Fugitive emissions from decommissioned mines

- Conventional road transport

- Entities covered in CPM but fall below threshold

It was believed that 400-500 liable entities were covered under the scheme (between 50 and 60 per cent of Australia’s emissions), with another 4-7% via equivalent carbon pricing (Clean Energy Future, 2011). The equivalent pricing was to cover remaining sectors (domestic aviation, marine and rail transport) through separate legislation. This coverage was reported to be comprehensive and is reasonable compared to other countries (i.e. Norway’s tax covers approximately 65% of emissions).

Distributional Impacts

As the worst carbon-emitting nation per capita in the OECD, many saw the Clean Energy Act 2011 as a crucial first step in Australia playing a role in global climate change action. Andrew Hewett, Oxfam Australia Executive Director (2011) stated that “Australia has until now failed to contribute its fair share to global efforts to fight climate change. Passing this legislation is a crucial step in playing climate catch-up”.

However, the passing of the bill was met with mixed responses from Australian industries and consumers, as people were fearful of broad economic as well as individual distributional impacts. A flurry of discontent ensued due to expectations of flow on to consumers of businesses passing through increased costs through the supply chain. Also, as a resource-rich, net exporting country, many were concerned that the carbon tax would negatively affect our industry competitiveness on the global stage.

Distribution of the tax burden is an important policy consideration, for reasons of equity and political feasibility (Goulder and Schein, 2013). In response to regressive distributional effects, the Government responded by confirming that revenue from the carbon tax would be distributed to businesses and households in the form of compensation. Tax cuts, increases in allowances, payments and benefits were introduced to offset the average rise in household costs of $9.90 per week. Approximately 50 per cent of scheme revenue generate was to be used to compensate households and industry, however it was not revenue neutral as per BC’s Carbon Tax. Industry assistance mechanisms (Deloitte, 2011) included:

- Jobs and Competitiveness Program for Emission-Intensive Trade-Exposed Assistances. $9.2billion over three years to 2015 in form of free permits and grants to increase energy efficiently.

- Manufacturing Industries Clean Technology Program – $1.2billion to assist manufacturing industries.

- Coal Sector Jobs Package – $1.3billion over six years to manage transitional impact.

- Energy Security fund – Assist electricity sector deal of free permits and cash of $5.5b over six years as well as pay for closure of very high emitting coal-fired generators by 2020.

Enter Tony Abbott

Move forward one year in the CPM, July 2013. Results so far are mixed. One side reports that emissions from electricity are at a ten-year low, renewable power generation has increased by almost 30% and the CPM had “clearly not been the wrecking ball it was dubbed” (Huffington Post, 2013). On the other hand, Economist Alex Robson of Griffith University, stated the main effect of Australia’s carbon tax has been to significantly increase electricity prices for households and businesses, with no reduction in CO2 emissions (Alex Robson, 2014).

Enter Toby Abbott and the argument for pro-business and “common sense action”. Arguing on the limited effect of the tax on emissions, problems with artificial price setting and anti-competitiveness, the Coalition set out to “clean up the mess of the Carbon Tax imposed by the previous Labor-Greens Government” (Kelly O’Dwyer, 2013). The proposed ‘Direct Action Plan’ concentrates on funding private industrial financed initiatives through taxpayer money to reduce emissions as well as sequestration of atmospheric C02 (Lubcke, 2013).

The plan may be more palatable for industry and pragmatic for decision-makers. However, it still infers an implicit carbon price that may actually be higher for Australian taxpayers and may encourage free riders.

Maybe Australia won’t throw out our “baby with the bathwater” (Kelly Rigg, 2013) as the latest update (6 March, 2014) finds:

“Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s plan to scrap Australia’s carbon tax regime took a hit this week after the Senate failed to pass legislation to dismantle the independent Climate Change Authority.

Christine Milne, leader of the Green party in the Senate, said, “The Greens, with the balance of power in the Senate, saved the Climate Change Authority … because we know it’s more important than ever that Australia doesn’t succumb to inaction on climate change…”

(Taxnews.com, 2014)

Watch this space.