Unfortunately, the only time I’ve ever visited Singapore was in transit on return to Australia from Malaysia. However, a fellow graduate resident, Joe Daniels at Green College is a “Singapore-aficionada”.

So I asked Joe, “What’s the traffic like in Singapore?” His replied that he was involved in a traffic jam when he first arrived, but didn’t face another problem in over a year there. His overall assessment was that Singapore had “one of the best systems I have experienced and one of the easiest places to travel around”.

These comments are consistent with Singapore recently being among ten cities honoured for their efforts to manage traffic congestion at the Inaugural C40 & Siemens City Climate Leadership Awards (London, Sept 2013).

But it wasn’t always this way. Let’s take a walk back into history thirty years….

Singapore’s traffic dilemma

The problem of traffic congestion is a vexing one for individuals, employers, city planners and policymakers alike in most major cities globally. For Singapore, it was a particularly pressing one. Singapore had transitioned as a strong emerging economy in the 1970s, with impressive economic growth and increasing wealth and urbanization of Singaporeans.

As result of this spectacular growth was the presence of an increasing amount of vehicles on the road. However, the geographic land characteristics of Singapore were providing a finite constraint. In 1975, there were three million people living in a land area of 633km2, with an income per capita higher then many Asian economies.

Something had to be done. Demand on the limited resource base of Singapore was reaching severity and the climate of Singapore is humid and hot, which further increased demand for private, air-conditioned travel. We have learnt that building more roads is not a conditional solution to road congestion as more cars fill the roads. However, in the confined land space context, building new roads was not an option for the nation. Therefore, Singapore had to look to policies to reduce kilometres driven and cars on the road.

The ALS and ERP

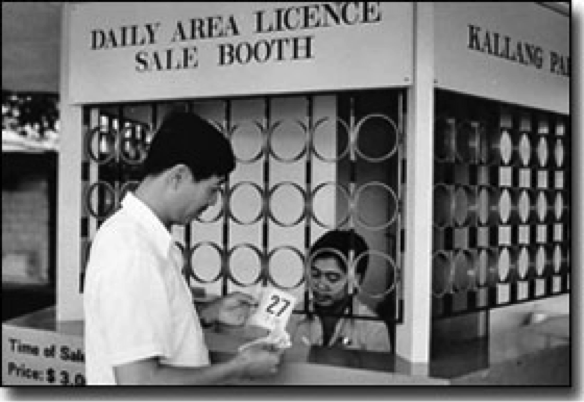

The Area Licensing Scheme (ALS) was introduced in 1975 and was considered “a bold move” as the first congestion pricing program internationally (Phang and Toh, 2004).

It set a price for driving in a ‘Restricted Zone’, which was located in the most congested part of the city. If a car or taxi entered the zone during the peak morning period (7.30-9.30am) they had to purchase a supplementary license sticker for their car. The stickers cost US$4.87 (daily) or US$99.68 (monthly) (2006 prices) and were checked by officials at the 22 points of entry to the Zone (Palgrave, 2006). In addition, public garages in the zone had their average fees doubled. The policy covered cars and taxi’s, but exempted cars with four or greater occupants.

The manual toll system was replaced in 1998 with Electronic Road Pricing (ERP). The tolls were based on size of the vehicle, route taken as well as the time of day.

It was seen as a superior system as it replaced the labor intensive ALS, which had a complicated breadth of licences (16 types), as well as having problems with illegal switching (Phang and Toh, 2004). In addition, the unlimited number of entries into restricted zone under-penalised contributions to congestion and made it difficult to equate Marginal Social Benefit with Marginal Social Cost (Phang and Toh, 2004).

Why price the roads?

The theory behind pricing road use has been extensively documented. Roads are a public good and a marginal user of the road consider their own private costs whilst ignoring the social cost of using the road.

Pricing the roads in Singapore is an example of a Pigouvian tax. The argument for a Pigouvian tax is as follows; increase the individual cost of usage by an amount that is equal to the externalities imposed by an individual driver. It is judged to be an effective response to tax the externality as drivers are more sensitive to money than the value of time.

Distributional effects on Singaporeans

Several criticisms have emerged in response to the ALS and ERP. To discourage driving, the price had to be set high initially to see a significant and immediate reduction. Phang and Toh (2004) stated that prices were considered to be above the optimal rate as the original target was for 25-35% reduction, whereas the initial reduction was as high as 45%. This has the effect of restricting driving in the zone to those with high incomes only.

The Government responded to this equity issue by ensuring there was adequate public transportation alternatives and additional parking outside the perimeter of the zone (Palgrave, 2008).

Effectiveness

Palgrave (2008) reported “the effects of the ALS were immediate and dramatic, far exceeding expectations”.

Commuters responded in a number of ways to the ALS. Responses included (Palgrave, 2008):

- Car-pooling: the number of cars with four or more occupants increased by 60%

- Public transport: for people who commuted into the Restricted Zone to work and who owned cars, the percentage who chose to ride the public buses rose from 33% to 46%.

- Time substitution: other commuters chose to enter the Restricted Zone before 7.30am. The percentage of car trips before 7.30am rose from 27% to 40% for drivers, and from 17% to 28% for passengers.

Palgrave (2008) stated that the nature and flexibility of these responses meant that pricing remains the least-cost strategy for reducing congestion (Palgrave, 2008).

Phang and Toh (2004) take another angle. They conclude that the success of the “draconian measures” can be attributed in part to the small size geographically of Singapore. This meant the grid remains largely insulated from non-domestic motorists. In addition, the authors state that the necessity of the situation resulted in unwavering government commitment. Furthermore, Phang and Toh (2004) attributed its success to a population that is characterized by “obedient, law-abiding citizenry”.

In relation to the ERP, Xie and Olszewski (2005) reported that there was a drop of 15% in inbound traffic, even though the rates were not as high as with the previous system. Per trip charging was attributable to this decrease. Phang and Toh (2004) stated that moved road pricing in Singapore much closer to optimal pricing.

The difference between the costs and revenue of the system are remarkable. Phang and Toh (2004) stated that what is undeniable is that the alleviation of traffic congestion has been achieved at minimal capital and operating costs. Reports have estimated that revenues from the pricing system were, on average, S$80million per year, with annual operating costs of S$16million and an initial capital outlay for the ERP of S$197million (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2011). However, it is not clear where this revenue went.

The other side of the coin

Did the congestion pricing just move the problem elsewhere? Phang and Toh (2004) argued that although it cut down vehicular traffic volume in the Restricted Zone, it merely shifted the crowding in time and place. People shifted their travel time to immediately before and after the restricted times and peak hour traffic was diverted to “new escape corridors” (Phang and Toh, 2004).

Conclusion

This very brief look at congestion pricing in Singapore has shown that time-variable pricing of roads can be an effective way to aid congestion problems.

However in this case, key factors specific to the Singapore context, such as size and urgency, were also part of the answer. Also successes in restricted zones must be weighed against the effects of the shifting of congestion.

It must be noted that the trajectory of only one particular policy was focused on in this blog. However, there are additional policies, such as certificate of entitlement fees and quotas, that have also contributed to reduced congestion in Singapore.

References

Elvik, R and Ramjerdi, F (2014) ‘A comparative analysis of the effects of economic policy instruments in promoting environmentally sustainable transport”, Transport Policy, Vol. 33, May 2013.

Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, (2011), Climate Change and Land Policy, [Puritan Press Inc., New Hampshire]

Olszewski, P and Xie, L., (2005) ‘Modeling the effects of road pricing on traffic in Singapore’, Transportation Research Part A.

Phang, Sock-Yong and Toh, Rex (2004), ‘Road Congestion Pricing in Singapore: 1975 to 2003’, Transportation Journal, Vol. 43, No.2.

WorldBank, ‘Relieving Traffic congestion ; the Singapore area licence scheme, 1975’, Available online at http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTABOUTUS/EXTARCHIVES/0,,contentMDK:21029453~pagePK:36726~piPK:437378~theSitePK:29506,00.html