For my first link, I chose to connect to Valerie’s Voice-to-Text task.

Differences in Experience

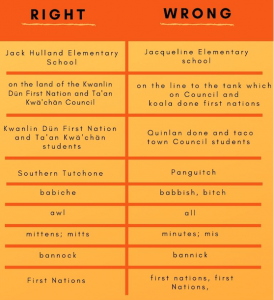

Valerie ran into many of the same problems as I did when completing this task, along with other deeper issues related to the functionality of the voice-to-text app. Whereas I used the iPhone app Transcribe for this activity, Valerie used a dictation tool built into Microsoft Word. Both Valerie and I had problems with the voice-to-text program picking up words incorrectly. However, this issue carried more weight in Valerie’s story than mine due to the topic of Valerie’s story. While I told a rather trivial story about my day and my dog’s haircut, Valerie’s story was about making drums for the grade 7 students at her school as part of the school’s connection with First Nations’ ways of knowing and doing. In telling her story, Valerie used several words and phrases related to traditional First Nations people and objects that are rooted in Indigenous cultures. The voice-to-text program that she used incorrectly translated several words and phrases related to her land acknowledgement and discussions of sacred and culturally significant objects. The most striking of these mistakes was the translation of “Babiche” to “Bitch.” Many of the translation mistakes made in my own story were laughable and overall unimportant, but this mistake, among others, in Valerie’s story are no laughing matter. I think that these translation errors signify the Western perspective that is dominant in these apps, and this can be harmful to students with cultures and backgrounds that are not reflected in these programs. Valerie makes an important point that teachers should always try to use the programs and complete the tasks they assign to students, as this is allows them to experience the process and any potential problems first-hand. My own experience with this exercise, and learning from Valerie’s experience, have opened my eyes to the many issues and limitations associated with these apps.

Differences in Design

Valerie’s user-interface for this task is another area where our submissions differ. Valerie added a design and visual element to her voice-to-text output, despite keeping the text unedited (as we were supposed to). The orange background, formatted title, and image of the drum give the piece a polished and pulled-together appearance. Her design choices are in stark contrast with the undeniably unpolished and mistake-ridden writing produced by the voice-to-text app, and I think this highlights some of the differences that she mentions between written and oral stories. As Valerie writes:

“Writing is planned, so it can be analyzed and stored forever; therefore, it is more likely to be carefully crafted” (para. 4).

Her design choices reflect this “carefully crafted” appearance that we typically expect with written pieces, whereas the actual writing produced by the voice-to-text app falls short.

Another difference in the appearance of our voice-to-text productions is that mine was chunked into paragraphs by the app, whereas Valerie’s was just one massive block paragraph. This is another important factor for teachers to keep in mind if they attempt to use voice-to-text app with their students. Students will have to manually correct mistakes related to word choice, spelling, grammar, punctuation, and paragraphing, and this makes for a very cumbersome experience for students. While there is potential for these apps to be valuable in helping students who struggle with written output, Valerie and I seem to agree that the limitations of these apps may outweigh the benefits.