Unit 6: Waorani

Lecture by

Alara Sever (@/alarasfoodways), Geneviève Lalonde (@/lastgen), Katerina Vyskotova (@/allofus)

Get to know Waorani peoples

Welcome to our blog lecture on the Waorani peoples of Ecuador. “Waorani” has many different spellings and names, such as Huaorani, Waodani, and Waos, but we stick with “Waorani” for consistency. In this lecture, we will be learning about the group’s traditional foodways, first foods, and the meaning these foods hold for their culture. We will also explore Waorani knowledge systems about the land and their worldviews. Finally, we will discuss the effects of globalization on the Indigenous group and their fight against climate change in both their community and on a global scale.

Yasuni National Park marked by dark green and the Waorani territory marked by light green occupied by the Waorani. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Localizaci%C3%B3n_de_Yasun%C3%AD_y_Huaorani_en_Ecuador.svg?fbclid=IwAR2sUJ7eA-51spSrgHGpd3cl141Y91SCgmjblAc5Im4D04v_bRnvm50K4Oc

Let’s get into it!

Waorani peoples are located in the Amazonian region of Ecuador, in between two rivers called Curaray and Napo, with the highest concentration of Waorani located in Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park, which now also serves as a Waorani ethnic reserve. However, their territory encompasses three regions: Napo, Orellana, and Pastaza. These current locations have not always been occupied by the Waorani, but with the arrival of 16th Century colonization, they are believed to have changed settlements.

The Waorani represent a small hunter-gatherer-farmer group that consists of around 2000 people, which are further divided into even smaller tribal subgroups, such as Taromenane and Tagaeri, the most well-known groups. Waorani peoples decided to pursue a life completely isolated from Western society’s influence, in order to maintain their traditional culture (Papworth, Milner-Gulland, Slocombe 2). Nevertheless, they still share a common language called Waorani or Wao Terero (also spelled Waotededo), which is considered a complete isolate, “a language unrelated to any other on earth” (Kane 1). In Wao Terero, the literal translation of Waorani is “they are true people,” and it carries a deeper meaning. Waorani use this name in order to distinguish themselves from cowodes, meaning nonhumans or outsiders. As we continue and touch upon the history of Waorani, keep this distinction in mind. As Waorani’s language and its etymology can bring us closer to their world, their food can tell us stories and help us understand who the Waorani really are.

A Waorani family on a canoe.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Huaoranis.jpg

Brief History

The Waorani have had a large presence on the world stage since their first recorded interactions with the Western world, during the rubber boom of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, and subsequent extractivist activities that required Westerners trespassing into their lands. The first official contact was made around the mid-20th century (Finer et al. 4). Because of the group’s relative newness to the outside world, their ancestral record is highly disputed, and some historians believe the reason they were able to live in isolation for so long was due to the elimination of other Indigenous populations along the Napo River during the initial colonization period in South America. This may have led to populations mixing and becoming what is now known as the Waorani. Another complication in genealogical tracing comes from the high rate of homicides within the group; this point was also used against the group in early recountings of interactions by white missionaries in order to paint a “savage” picture of the tribe. This depiction was further exacerbated at the time of the Palm Beach killings (a.k.a. Operation Auca) of 1956, wherein five missionaries attempting to convert the Waorani tribe to Christianity were killed by the warriors (High 31). However, the Waorani see themselves as prey and react strongly to intrusions because of their fluid connection with nature. For them, there is nothing but predator and prey in nature, and since they are from nature and have remained so, they are not able to see themselves divorced from nature in the way Westerners do. Perhaps because of this, relationships with the state have often been tense, as Ecuador has not shown respect towards the Waorani way of life. In recent decades, due to further involvement with missionaries, many Waorani were converted to Christianity and married cowode (High 43).

Waorani cosmology is similar to that of other Amazonian groups, wherein there is no differentiation between what Westerners would consider to be the spiritual part of themselves and their reality (Erickson 952). For the Waorani, these two are blended together, and spirits live among us, as important as physical beings.

Current State of the Group

The Waorani have been under international scrutiny, having recently dedicated themselves to being strong advocates for Indigenous rights and self-determination, especially because of their geographic context, which places them in a high-extraction hotspot: oil extraction, deforestation, and intensive cattle farming – the Amazon has been the victim of unrelenting development for decades (Etchart 2). Markedly, the illegal extraction of crude oil on their lands has left spills and health risks that threaten not only the health of the group, but of the rainforest’s well-being (Collyns). For example, in 2012, a consultation process with the community for a project development was followed through inappropriately, yet still resulted in the sale of Waorani land for development. In retaliation, the Waorani, with Nemonte Nenquimo as their leader, took the Ecuadorian government to court in 2019 and won, marking a global landmark for Indigenous rights and self-determination. This has been their most noteworthy achievement to date, which is very impressive considering how the group has only made contact within the last 60 years. However, much more groundwork needs to occur. Watch this video of Nemonte Nenquino speaking about land preservation. Transcript included in the video.

Given that Amazonian governments have turned a blind eye to the destruction of the Amazon, the rapid rate of deforestation must be addressed quickly. Because the Waorani are immensely concerned with this issue, they have taken action and are currently mapping their land under the Ceibo Project (Amazon Frontlines). From hunting trails, plants with medicinal or other properties, fishing areas, and other relevant nodes, their GPS-tagged locations will be stored in a library. This digital record will become increasingly important, given that the group is already struggling to find game. Instead, like countless other altruistic Indigenous groups (e.g.: groups in Northern Canada that have given up hunting caribou), the Waorani have replaced a part of their hunting with farming cacao, under the Association of Waorani Women of the Ecuadorian Amazon (AMWAE). This association, which focuses on women’s empowerment, works with global partners to create a source of income that respects Waorani culture by creating crafts such as weaved baskets and cacao initiatives. This allows the Waorani to participate in a formalized market economy that pays them above the market price for their product, whilst allowing them to not be wholly dependent on these revenues. However, concerns are mounting as protein scarcity is bound to increase.

Waorani women selling handmade crafts like weaved baskets, necklaces, etc.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Artesan%C3%ADas_huaoranis,_Archidona.jpg

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has been an enormous pressure on the group, given that they are more susceptible to infection, and if they were infected, the virus could effectively wipe out a whole population of people, given their small size. This would erase their history, as there are currently few written records of the group’s history, knowledge, and other relevant information. Much of this information, as in other Indigenous groups, is retained by elders or other community members.

This is another factor in tensions the group has with Ecuador. The state’s failure to act on the pandemic has left the Waorani and neighbouring groups at a high degree of risk. Without speaking of the incalculable cultural loss, the disappearance of this group or others like it would result in a loss of knowledge about food cultivation in the Amazon, seasonal animal behaviour, and paths, and would leave a large hole in a place that is otherwise quite defenseless on its own.

Relevance of the food and how it connects to their culture

Because their diets and medicines are simple and comprised of raw, one-ingredient foods, theirs has been hailed as more effective than other complex diets. Their diet has even been observed by and influenced Paleo Diet founders. Though we only go in-depth into oonta and the white-lipped peccary, Waorani have also been known to plant and consume crops like manioc, plantains, sweet potatoes, and chicha.

Waorani agricultural science is based on slash-and-mulch especially manioc slash-and-mulch because manioc is the most consumed tuber in Waorani foodways (Lu and Wirth 235). While the slash-and-burn agricultural practices proved to diminish the crop yield and the nutrients in the crop, slash-and-mulch has proved better crop yield and it also prevents loss of nutrients in the crop (Joslin et al. 1).

Oonta

Curarea tecunarum is a Waorani hunting poison that is used in a blowgun dart. It is consumed daily within the flesh of various poisoned animals, such as monkeys and birds that are located high in the rainforest. C. tecunarum has a high frequency of consumption in the Waorani diet, only exceeded by three staple foods: manioc, bananas, and the white-lipped peccary. The Waorani refer to the C. tecunarum vine and poison as oonta, a word that is not present in Spanish or English vocabulary. Looking closely into the word oonta, the double “oo”s in Wao Terero signify various associations to dart poison, blow, meat, and hunt (London 465). The oonta vine has a flattened shape which climbs trees and grows in altitudes ranging from 350 to 1,000 meters. Waorani poison preparation and utilization is unlike the rest of South American Indigenous groups, due to their isolation from outside contact until recent years. Usually, other Indigenous groups prepare the poison with numerous ingredients, but the Waorani only use C. tecunarum.

Location

Oonta is a significant foodway of the Waorani, because it is presently only hunting poison only used by the Waorani, although a few other Indigenous groups have used it in the past. In fact, the species name, Tecunarum, comes from the Tecuna Indigenous group, which was also known to use this plant (London 267). Oonta is also a location-specific plant that only grows in remote regions such as Yasuní National Park. This region-specific plant knowledge is reflected in Waorani ethnobotany, which refers to the uses of endemic plants through traditional knowledge of local people.

A Brown Woolly Monkey

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brown_Woolly_Monkey.jpg

Preparation

Oonta is the most elaborately prepared plant in Waorani culture. First, the bark from the vine is shaved, and the shavings are filtered with water in a funnel and then into a container. After, the liquid obtained from the filtering process is boiled and brushed on the darts, which are made with two long wood pieces cut in half and wrapped together with vines. The oonta is then left to dry. This final processed version of the poison is referred to as ome, which is the more potent version of oonta, because it is ten times more paralyzing, yet still safe to digest. Consistently ingesting the ome poses no harm to the Waorani, who successfully prepare the poison effectively enough to hunt the animals by enhancing the poison in oonta using their traditional knowledge systems and ethnobotany. Because of their extensive traditional knowledge, the Waorani can ingest this poison on a daily basis without any health consequences due to biochemical changes that occur in the transition from the raw oonta to the final version of cooked ome before it is consumed (London 471).

Other areas of use

Oonta has additional properties other than serving as poison. For example, oonta is used in some Indigenous groups as birth control to reduce fertility by ingesting excessive amounts or increasing fertility by ingesting small amounts from the hunt. However, Waorani is one of the three groups in Ecuador that does not use any plants for fertility purposes, due to the group’s already warlike nature. As a result, the Waorani members killing each other often in wars does not allow for a population increase. However, though unintentional, the fertility rates of the Waorani increase in May due to their higher consumption of wooly monkeys, and the oonta in the meat causes a fertility spike, which results in most Waorani individuals being born in February. The reason the Waorani consume more monkeys in May is because it is when the monkeys are the fattest, due to more fruits being available (London 500).

Another property of Oonta includes the ability of significantly lowering blood pressure, causing the Kawymeno Waorani to have one of the lowest recorded blood pressures in the world, as well as no history of recorded cardiovascular diseases (London 8). However, with their integration into modern life the Waorani are experiencing cardiovascular diseases due to their change of diet. Lastly, Oonta has healing properties when applied to external wounds. C. tecunarum is increasingly used in anesthesia as a muscle relaxant.

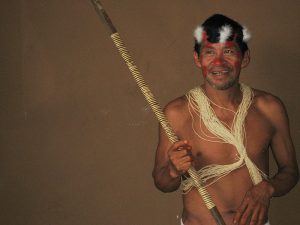

A Waorani man with a blowgun dart. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Huaorani_leader.jpg

White-lipped peccary

White-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari) is considered one of the staple foods of the Waorani. It is regularly consumed, being one of the group’s favourite mammals, due to its very enjoyable garlic taste.

Peccary hunting

Peccary hunting for Waorani by itself is a very important process, relying on cooperation and contribution from both men and women. It carries a high social significance because it brings all Waorani members together. From this simple act we can learn a lot about how Waorani society functions. For instance, women and men are valued equally, hence, Waorani live in an egalitarian society. Peccary is mostly hunted with wooden spears with wooden notches on top that, after the spear is inserted, stay inside the animal’s skin. Traditionally, the men are the ones who hunt the animal, but the women are the ones who actually kill the animal, with knives (London 90). In addition, white-lipped peccary hunting does not occur year-round, despite its consistent availability. Peccary is consumed seasonally due to its particular taste, which is based on the plants it consumes. Waorani hunt white-lipped peccaries only when the animals ingest wegamoñi (wild garlic). This specific plant not only gives peccary meat the delicious taste of garlic, but it also makes the hunting process much easier. Peccary who consume wegamoñi can be traced from very far, thanks to their strong garlic odor. Waorani use this knowledge to hunt peccary only when they know the meat tastes good, and is easy to find. On the other hand, when the peccary consumes a plant called Wengamo, the Waorani stop hunting peccary, because its meat takes on a very unpalatable taste (London 246). From this, we can see that the Waorani’s food sources are affected by the plants that peccary consumes, rather than the abundance of peccary itself. Waorani’s foodways of animal consumption are therefore plant-driven.

Nutritious delicacy

Peccary consumption is introduced to Waorani infants at only 6 months of age by feeding them with mostly peccary fat, which is Waorani peoples’ favourite part of the animal to consume. Like all other Indigenous groups, the Waorani do not waste any part of the animal they hunt: they consume the whole peccary, but its hooves and colon are never eaten. Hooves are inedible and colon is used for medical purposes (London 201). The Waorani also have developed a special cooking method that allows them to preserve peccary meat, which involves cooking it on a fire and flipping it every 30 minutes, creating a type of smoked meat that can last up to many weeks. Therefore, peccary increases Waorani’s food security.

Nevertheless, there is a reason behind why the peccary plays such a big role in the Waorani diet. Due to peccaries’ high consumption of phytochemical plants that function as antioxidants in human bodies, consuming peccary has immense health benefits. Once the peccary consumes these plants and its digestive system breaks up the nutrients, it is much easier for the human body to absorb them rather than directly consume the plant. Thanks to the Waorani’s awareness of the plants the peccary consumes, they do not need to eat the plants by themselves; just like Westerners eat plant nutrients through eating beef. The white-lipped peccary is a multifunctional staple food: it provides the Waorani with antioxidant-rich macronutrients, and it also prevents bacterial disease through its antimicrobial compounds (London 256).

White-Lipped Peccary

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:White-lipped_Peccary_Tayassu_pecari_(6782072719).jpg

Waorani and peccary interconnected

Peccary hunting and manhood are closely tied together, as this activity marks the transition from a boy to a man in Waorani’s culture. Hunting, choice of prey and creation of hunting weapons is, in Waorani culture, considered the way of becoming a man (Rival 291). Just before their adolescence, boys start to learn how to craft their own hunting spears and C. tecunarum poison. As soon as they are able to do this and survive their first official peccary hunting, the young boys are not considered children anymore, they become men, “fierce warriors” (Rival 291). In addition, peccary hunting is a bonding experience and most importantly, an act that every Waorani member carries deeply in their heart.

Waorani and Globalization

Their involvement in oil activities and formal schooling have changed Waorani life, and today, many Waorani youth prefer to be in cities, learning and talking mainly in Spanish. The Waorani continue to experience rapid cultural change, which, although originating with missionary contact, has more recently been enhanced by the oil companies and integration into the market economy. The Ecuadorian government has been justifying oil extraction in the Amazon as buen vivir and “development” for the Indigenous communities (Lu, Valdiva, Silva 13). However, Indigenous Amazonian groups are undeniably the ones who are most harmed by the oil companies and, yet, get the smallest benefit.

Globalized Foodways

As a result of outside contact, the Waorani diet, which is traditionally acquired by subsistence activities such as hunting and gathering, is now declining and shifting towards purchased food in the protectorate oil fields. While there are still isolated groups of Waorani that practice a strict hunter-gatherer diet, others are relocated in accessible oil protectorates, adopting Western foodways, and thus abandoning their traditional foodways. The Waorani diet has become dependent on purchased food, and in order to afford these new foodstuffs, they have also become dependent on oil activities that are very physically demanding and pose health risks. Some of the global foods that have entered the Waorani diet are rice, noodles, cookies, and soda (Lu, Valdiva, Silva 144). As the consumption of culturally meaningful food decreases, food-related illnesses such as diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular diseases- have risen in Waorani communities due to their high intake of cheap carbohydrates and sugar that are nutritionally inferior.

While the consumption of forest game such as woolly monkeys and peccaries with high cultural significance have diminished, the consumption of domestic meat such as chicken and beef is constantly increasing. Also, the staple crops of Waorani including manioc, plantains, and bananas, are being replaced with vegetables that are obtained from the markets, such as tomatoes and onions (Lu, Valdiva, Silva 146). Finally, this type of dependence has increased food insecurity due to abandoning subsistence activities.

Traditional plant knowledge

Initially, missionaries started the process of eliminating traditional Indigenous knowledge by replacing them with Western values through formal schooling and health clinics. Waorani in the global world no longer make use of traditional knowledge, because it is not appropriate for the current way of life. In communities where modern medicine is attainable, they consult medicinal plant knowledge less frequently. Also, formal education provided to the Waorani children does not include Traditional Ecological Knowledge in its curriculum; it only addresses raising kids in the model of the globalized world (Weckmüller et al. 10).

Oil roads

The oil access roads that are built into the Yasuní National Park have both direct and indirect impacts on the Waorani people. The direct impacts of these roads include habitat destruction, soil erosion, and wildlife extinction. The indirect impacts include deforestation, as these roads are utilized by illegal loggers who access interior routes in search of valuable cedar trees (Finer et al 10). Finally, overhunting occurs due to unsustainable hunting of vulnerable species. The Waorani, who traditionally used blowguns, have now switched to guns in many cases, and use the free transportation provided by the oil companies to participate in wildlife trade, as well as selling other handicrafts as a source of income. Moreover, due to limited economic opportunities provided by selling handicrafts (which is generally undertaken by Waorani women), the sex trade has started in order to afford market goods, resulting in an increase of teen pregnancies (Alban Canpana 41).

Climate Change

Waorani climate change leaders are increasingly teaming up with various NGOs such as the Ceibo Alliance, an Indigenous-led organization that consists of Kofan, Sinoa, Secoya, and Waorani peoples in collaboration with Amazon Frontlines, in order to create a model of Indigenous resistance and international support in protecting Indigenous territory (Kessler 2).

Alicia Cawiya, one of the Waorani leaders of the movement against oil exploitation in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alicia_Cahuiya,_Caso_Tagaeri_y_Taromenani.jpg?uselang=de

Wao Öme

The Waorani people call their lands wao öme, which refers to the Waorani land and their role in its protection. Wao öme signifies a place of abundance in which an interdependence between Waorani and non-human elements of land is connected to the concept of Waponi Kiwimoni (living well) (High 304). However, oil extraction threatens the deeper understanding of Waponi Kiwimoni that comes from the interconnectedness of Waorani to non-human beings in wao öme. As a result, the increasing concerns resulted in cooperation within the Waorani and also outside groups such as NGOs and environmentalist organizations. The Waorani are actively involved in state-sponsored and international conservation projects. This is made possible by their attaining technological training and employment within NGOs in environmental mapping and monitoring (High 319). In this way, they challenge the oil companies with the same concept of development that was used to legitimize it. For example, digital mapping, which locates different flora, fauna and important sites, is different from how the Waorani experience wao öme. Kowori (outsider) technology, however, is still highly valued.

Wao öme inherently contradicts the peaceful understanding of the Western conservationist perspective due to its antagonistic relationships with other human members and non-humans. However, the Waorani uses strategic translations in presenting the Wao öme through environmental discourses in order to accommodate Western values and to take its pace in Western eco-politics (High 312).

Another achievement that stems from global partners and NGOs is evident in making clean water accessible to people located in the Amazon including the Waorani. Women on the oil roads wake up early every morning to catch the company bus to collect their daily ration of clean water. However, the Waorani are still deprived of adequate clean water despite the promises of the oil companies. Working together with Amazon Frontlines the Waorani are trained to lead the installation and the maintenance of the rainwater catchment system that provides the Indigenous communities with clean and safe drinking water, which has resulted in improved digestive health in Waorani (Kessler 2).

Overall, some of the benefits that come from the Waorani interacting with the globalized world include international solidarity for Waorani resistance for the protection of their rights and their lands, programs that support women livelihoods sustainably, and viable solutions to pollution such as the water program.

A picture of Nemonte Nenquimo, a Waorani climate change leader, the co-founder of Ceibo Alliance. TIME 100’s annual list of the most influential people in the world named Nemonte Nenquimo as she continues fighting to protect her ancestral territory, culture, and way of life.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nemonte_Nenquimo.jpg?uselang=de

Here, we leave you with a Waorani song.

Optional readings/Videos:

- This is my message to the western world – your civilization is killing life on Earth, Nenquimo, Nemonte. (Op-ed). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/oct/12/western-worldyour-civilisation-killing-life-on-earth-indigenous-amazon-planet

- Victims and Warriors: Civilized Victims, High, Casey https://muse-jhu-edu.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/chapter/1476959/pdf

- Waorani The People (video). https://vimeo.com/295917626

Thanks for reading!

Works Cited

Alban Campana, Dayuma. Teen Pregnancy on the Oil Road: Social Determinants of Teen Pregnancy in an Indigenous Community of the Ecuadorian Amazon, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2015.

Erickson, Pamela. Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World’s Cultures. “Waorani”. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 01/01/2003, https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/referenceworkentry/10.1007/0-387-29907-6_99

Etchart, Linda. “The Role of Indigenous Peoples in Combating Climate Change.” Palgrave Communications, vol. 3, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-4.

Finer, Matt, et al. “Ecuador’s Yasuní Biosphere Reserve: A Brief Modern History and Conservation Challenges.” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 4, no. 3, 2009, pp. 034005.

High, Casey, and Project Muse. Victims and Warriors: Violence, History, and Memory in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 2015, doi:10.5406/j.ctt13x1m0q.

High, Casey. “Our Land is Not for Sale!” Contesting Oil and Translating Environmental Politics in Amazonian Ecuador.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, vol. 25, no. 2, 2020, pp. 301-323.

Joslin, Aaron H., et al. “Five Native Tree Species and Manioc Under Slash-and-Mulch Agroforestry in the Eastern Amazon of Brazil: Plant Growth and Soil Responses.” Agroforestry Systems, vol. 81, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-14

Kane, Joe. savages. Knopf, New York, 1995.

Kessler, Rebecca. With no Oil Cleanup in Sight, Amazon Tribes Harvest Rain for Clean Water. Newstex, Menlo Park, 2018.

London, Douglas S. Diet as a Double-Edged Sword: The Pharmacological Properties of Food among the Waorani Hunter-Gatherers of Amazonian Ecuador, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2012.

Lu, Flora, and Ciara Wirth. “Conservation Perceptions, Common Property, and Cultural Polarization among the Waorani of Ecuador’s Amazon.” Human Organization, vol. 70, no. 3, 2011, pp. 233-243.

Lu, Flora, Gabriela Valdivia, and Néstor L. Silva. “Oil as Risk in Waorani Territory.” Palgrave Macmillan US, New York, 2016.

N/A. “Hunt with the Amazonian Waorani Tribe.” The Paleo Diet. 2020. https://thepaleodiet.com/hunt-with-the-amazonian-waorani-tribe

Papworth, Sarah, E. J. Milner-Gulland, and Katie Slocombe. “The Natural Place to Begin: The Ethnoprimatology of the Waorani.” American Journal of Primatology, vol. 75, no. 11, 2013, pp. 1117-1128.

Papworth, Sarah. “Indigenous Peoples, Primates, and Conservation Evidence: A Case Study Focussing on the Waorani of the Maxus Road.” Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016.

Rival, Laura. “The Attachment of the Soul to the body among the Huaorani of Amazonian Ecuador.” Ethnos, vol.70, no. 3, 2005, pp. 285-310

Weckmüller, Holger, et al. “Factors Affecting Traditional Medicinal Plant Knowledge of the Waorani, Ecuador.” Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 16, 2019, pp. 4460.