This book has taken us in an interesting turn, and I see why it’s last on the syllabus. It parallels almost every. other text in a very intriguing way, opposing Guaman Poma and mirroring Rigoberta Menchu. What is most interesting to me, though, is the conversation about translation. Specifically, how Bruce Albert wrote the book by listening to Kopenawa and translating all of it into French. As my late French immersion didn’t do me much good, I read the book in English, and hence lies another layer of translation. In this way, I’m reminded of the Popol Vuh, and questions are raised about the complete authenticity and accuracy of the writing. Based on how blatantly anti-white people it is, there is a sense of the faithful meanings and proper translation being done. As well, it is reminiscent of Yawar Fiesta in its use of words in their original language to convey their exact meaning.

Another thing to consider in this book is how Albert’s background as an anthropologist influences his research. There is a deep-rooted history of anthropology looking at Indigenous people as damaged individuals to solve and document, ignoring their own agency. The ‘story of Indigenous deficiency’, as Daniel Heath Justice calls it, implies that Indigenous people’s beliefs and traditions have led them to a state of moral lacking, and that is what causes all of their distress. This ignores, oh I don’t know, colonizers colonizing. Often anthropologists come at oppressed cultures with a damage-based research lens. What’s interesting here is how Albert learns to use a desire-based research lens, documenting what Kopenawa wants to pass on to the white world. He even goes so far as to adamantly distance himself from other anthropologists, claiming this is no longer his work but really his way of life. He is not like the other anthropologists, he’s so different.

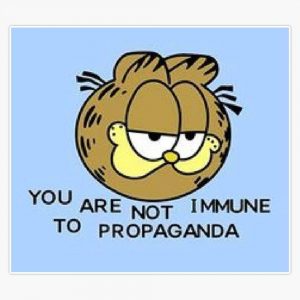

This ties into something Kopenawa talks about, which is how white people need their knowledge written to be passed down and remembered. This contrasts greatly with Yanomami culture, where their knowledge is ingrained in their thoughts and their speeches. This means that Albert is then coming in as a knowledge translator, taking the white man role to write down his white man words. As much as this accomplishes Kopenawa’s goal of spreading knowledge, how effectively does this contribute to the continuation of needing to—for lack of a better term—Westernize Yanomami life and Indigenous knowledge in general?