Data Collection

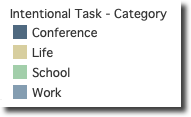

Legend – categories of intentional task (where I intended to focus my attention).

The day in my life that I chose was one where I knew I had specific tasks to focus on, but where I also know I was likely to be distracted. I chose the second day of a virtual conference that I was attending. This conference mostly involved video presentations, included one social virtual activity and was being held live, with recorded content also available. This conference took place on a day that I also had some work to do, and had a group project meeting (school). I chose a day that was heavily virtual – school, work, and the conference are all activities that I participate in virtually. I did so because throughout Covid I noticed a growing awareness of the inability to focus after hours on the computer, and I wanted to see how this would show in the data, especially when attending a heavily engaging event like a conference. The unique part of this conference is that all of the seminars are recorded and made available very quickly. After day 1 of the conference, I knew I would need more breaks, and so I was deliberate in parts of the conference to listen to the recordings while purposefully multitasking (I also had many chores to do that day!).

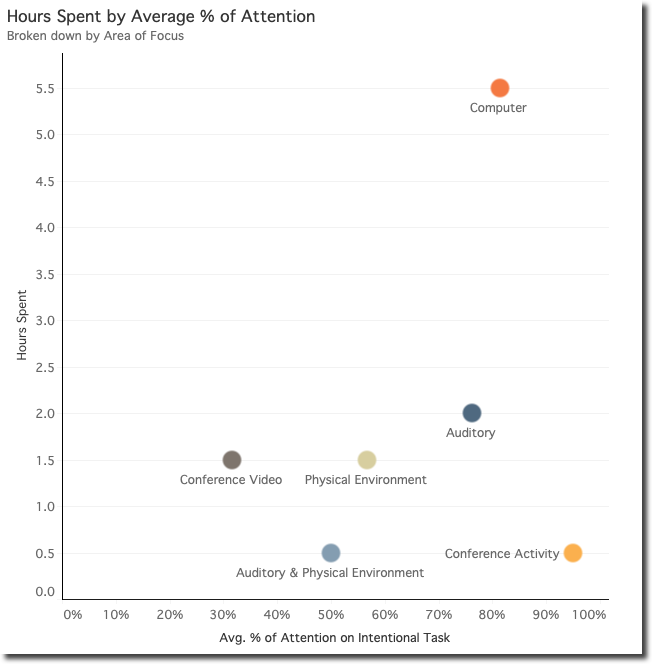

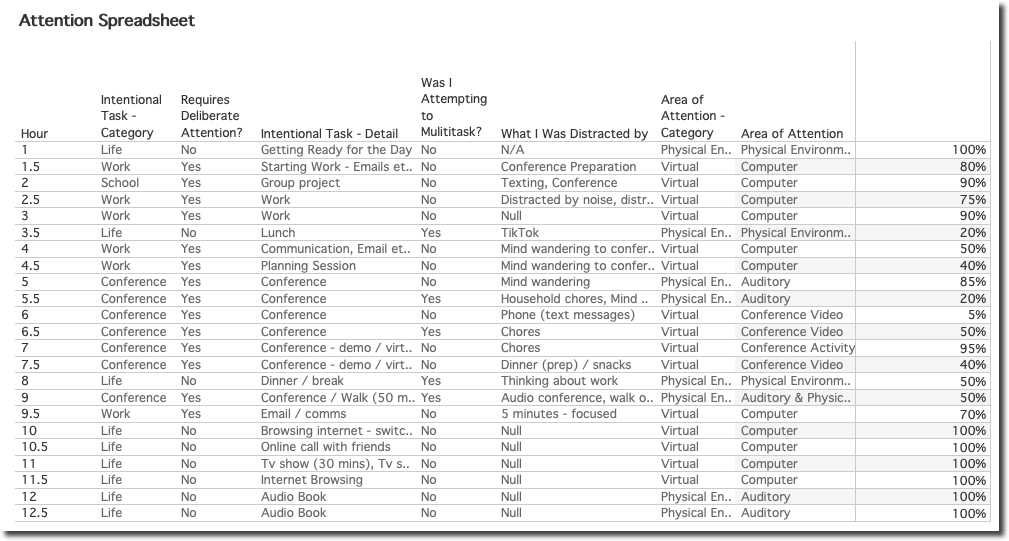

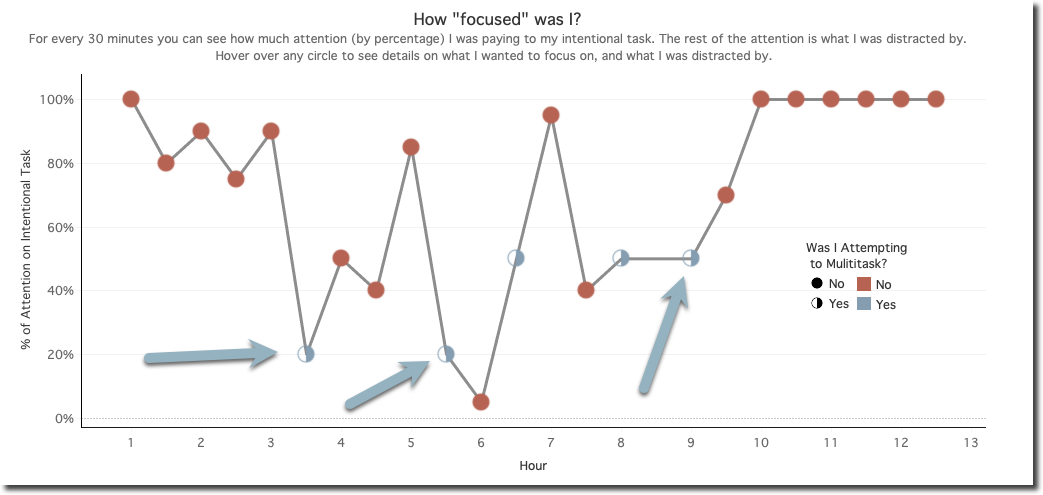

I began by creating a spreadsheet to help me track where my attention was. I divided the day into 30 minute segments and took notes about what I wanted to focus on (“intentional focus”), what I was actually focused on, and the % of attention I think I was paying to the intentional focus activity. I also categorized whether the intentional task requires deliberate attention, whether I was attempting to multitask, and the “area of attention”.

Enlarge

Data Analysis

I developed a dashboard to help me explore my day and investigate any patterns in my activity. I used the exploration and building of the dashboard to find the insights discussed further in this blog post. Here is a quick walkthrough (the dashboard and video are meant to be self contained, so may repeat some components discussed here.) The walkthrough shows the full-scale version of the dashboard which can be found here: Attention Dashboard

A smaller version (that “fits” in WordPress) can be interacted with here:

Key Findings

Device Overload & A Few Stats

I spent my day interacting with screens! Of the 13 hours of recording, I spent only 4 hours not looking at a device. However, even in those 4 hours I was listening to either a conference recording or an audio book.

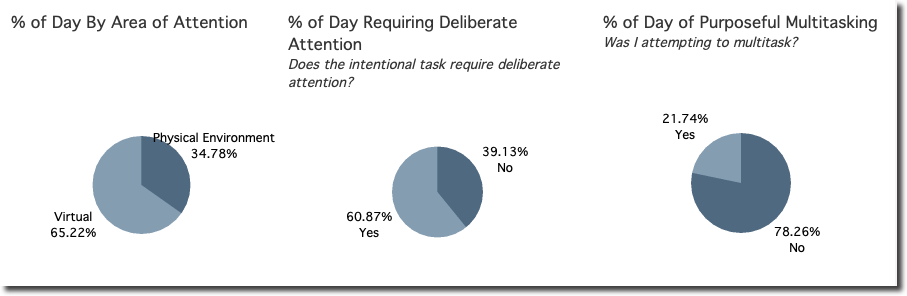

Using categories of “Virtual” and “Physical Environment” (to be anything not-device related) I spent just over 65% of my day paying attention to virtual devices. I purposefully multitasked for about 22% of the day, and attempted to focus on tasks that require deliberate attention for just about 61% of the day.

Multitasking

One pattern that I find interesting is when I look at the data based upon whether or not I was attempting to multitask. In these scenarios the “distraction” is really a secondary intentional task. My first instinct was that these deliberate multitasking sessions were followed by improved focused attention – however, this may be a misleading interpretation. The multitasking sessions involved lower focused attention because I was being deliberate. So, the upswings of attention after a multitasking event may just be a data collection issue. Reconsidering the data then, perhaps I was having difficulty with focused attention which was why I had so many multitasking events in the middle of my day.

Enlarge

When I look further into the data, I can see that I only really attempted to multitask during life and conference events. And that conference event multitasking brought my attention to 40%.

Concluding Thoughts

De Castell and Jenson (2004) point to examples of asymmetrical attentional relations, where attention can be paid unidirectionally rather than reciprocally in an argument against Goldhaber’s propositional that attention must be “paid back”. While I spent some of my day being paid attention to (in a group meeting, and in an online chat with friends), the majority of my day was simply ingesting information. Even then my attention was often divided, either purposefully or not. My experience of multitasking is closer to the “youth” than the “elder”, I do multitask, however my thought process regarding attention is closer to traditional views of attentional economy.

The data I have shared and visualizations created are somewhat cleaned up versions of originally “messy” data collection. Upon reflection toward the data cleaning process, I recognize that I developed a data collection and categorization framework that seemingly put emotional value toward “paying attention”. In the details about what I was distracted by I have a negative association when writing and reviewing: “mind wandering, got distracted by phone, thinking about other”. I felt bad that I was distracted when I was not intending to – when I was purposefully multitasking, less so.

De Castell and Jenson (2004) propose a new way to consider attention in an educational context with a need to “better identify and develop forms of productive engagement in which dynamic, multimodal learning environments are animated by students’ deliberate and sustained attention” (De Castell & Jenson, p. 18, 2004). If I reframe my day toward learning – I was engaging with various kinds of media (audio, video), communications (text, video conference), and I was making connections between conference materials and my day-to-day work. If I look at what I was distracted by (when it wasn’t TikTok), when I was working I was distracted by the conference, and vice-versa. These could be considered distractions, or they could be considered as opportunities for re-engaging with material in a new way, for contextualizing new information, or for being creative in my choices of digesting various forms of media. Indeed, what I was taking part in could be the organic convergence of media (Jenkens, 2001) – where the context can be considered an educational one. Reconceptualizing the digestion of media in this way makes it seem a standard of the 21st century consumption of information, rather than a negative action.

References

De Castell, S. and Jenson, J. (2004), Paying attention to attention: New economies for learning. Educational Theory, 54: 381-397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-2004.2004.00026.x

Jenkins, H. (2001). Convergence? I Diverge. I . MIT Technology Review.