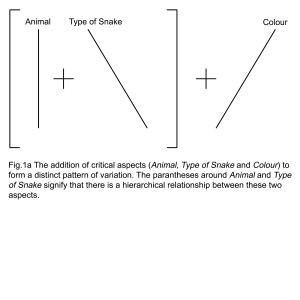

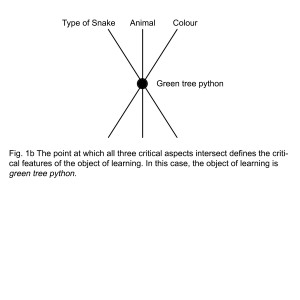

The crux of Variation Theory (VT) is that humans learn through discernment and that discernment requires exposure to variation (Marton & Trigwell, 2000). For example, we can identify an object as a green tree python because we are able to discern specific traits related to that object. We know that the object is an ‘animal’, which is one dimension of variation that includes ‘snake’ as one of many possible values (other values include dog, mouse elephant, etc.). Next, we identify a second dimension of variation—’type of snake’—of which ‘tree python’ is a single value. The final dimension of variation is ‘colour’, of which ‘green’ is a single value. Note that there is a dominance relationship between the dimensions ‘animal’ and ‘type of snake’ with animal being superordinate and type of snake being subordinate. That is, you cannot know that an object is a ‘tree python’ without first knowing it is a ‘snake’. There is no such relationship between colour and the other two dimensions. Therefore, it is not necessary to know that this is a ‘tree python’ or a ‘snake’ to know that it is green. A person must be aware of each of these dimensions of variation simultaneously to know that the object is a green tree python (Fig. 1a). Because the dimensions of variation—animal, type of snake and colour—are required to identify the object, we refer to these as critical aspects. Within each critical aspect is a range of values that we can use to identify an object or concept (e.g. green tree python). We refer to these values as critical features. We can identify any specific object or concept based on its critical features (Fig. 1b; Ling, 2012).

Importantly, humans cannot discern objects or concepts through sameness; for this we require variation (Marton & Trigwell, 2000; Ling, 2012). For instance, a person cannot understand the concept of Haiku poetry if they are exposed to Haikus only. They must also experience other types of poems so that they can discern the critical features (e.g. three, non rhyming lines in five, seven and five syllables) that constitute a Haiku. In this example, types of literary works, poetic structure and literary devices may all be critical aspects that help discern the critical features of a Haiku. It is up to teachers to deliberately introduce dimensions of variation (critical aspects) that enable students to identify an item’s critical features.

So far, the examples I have provided for implementing VT are relatively straightforward, perhaps even intuitive. This is because the items I have described represent relatively simple concepts that require somewhat simple patterns of variation. In the green tree python example, I depict the pattern of variation employed in figure 1a. Here, I introduced variation along each aspect individually until all three aspects intersected to reliably identify a green tree python (Fig. 1b).

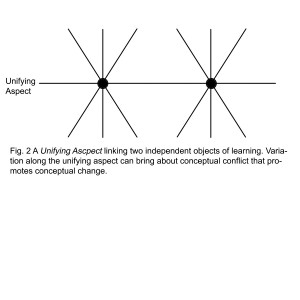

As teachers start to discuss more complex concepts (such as scientific theories), the applicability of VT becomes less obvious. I will take the example of using Evolutionary Theory to explain the diversity of life on Earth. For a theory as complex as this, there is no simple pattern of variation that we can introduce that will help students discern the process of evolution. To some extent, students need to understand principles of ecology, genetics and molecular biology—each a scientific discipline in its own right—to discern the process of evolution. So then, which critical aspects of each discipline do we need to vary so that students can discern the critical features of evolution? This is a daunting question and one that is hard to imagine answering in a single semester or school year. Furthermore, how can we convince students that Darwinian Evolution provides the most parsimonious and intelligible solution for explaining the diversity of life on Earth? I suggest that teachers can introduce layered patterns of variation connected by unifying aspects (Fig. 2; an idea which I develop in the following section) that introduce conceptual conflict leading to conceptual change. In identifying appropriate unifying aspects, teachers must carefully consider how they want students to see what variation theorists refer to as the object of learning.

In the examples above, the items that we are trying to get students to discern (e.g. a green tree python, Haikus, Evolutionary Theory) are called the objects of learning. It is important to note that the object of learning is different than a learning objective. A learning objective is a predetermined endpoint that we want students to achieve. The object of learning is an object that we want students to experience. For students to experience an object the way we intend them to, we must first identify its critical aspects. This is difficult because humans do not experience objects (which include concepts) in their totality; we all focus on different critical aspects. Therefore, teachers and students may be focusing on different aspects of the same object. This misalignment between how teachers and students view the same object of learning is where conceptual conflict arises (Ling, 2012). Using VT, we can create conceptual conflicts that allow students to understand deficiencies in their prior knowledge of an object of learning and promote conceptual change that allows students to fundamentally alter how they view that object.