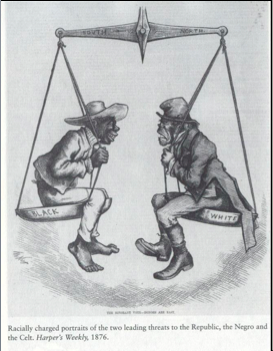

For a long time, the abstract concept of race has been one that has remained largely enigmatic for me. Given that it is a tabooed subject of conversation in a supposedly “color blind” multicultural society that is impartial to visible physical differences, I had not sought to explore the controversial topic further beyond our academic study of racial theory in Sociology. However, during term 1, I had the opportunity to take an Urban Studies 200 course, which primarily undertook critical perspectives in its approach to the cities and introduced us to a multiplicity of theoretical ideologies relating to urban regions. As part of one of the lectures on racial identity in the city, professor Wyly brought up that race and ethnicity should be seen as historical and geographical “processes”: it is inappropriate and outdated to see them as categorical systems. Initially, I recognized the validity of this perspective, as it is undoubtedly the case that how we perceive race has shifted over time. For example, as illustrated by the 1876 issue of Harper’s Weekly, in the 1870s Celts and the Irish were not understood to be white in the United States; however, now we can definitely “classify” them under this heading.

Nevertheless, we cannot completely disregard the view of race as a categorical system, for it remains forcefully present within our society. Indeed, in his book “Race”, Jake Kosek (2009) identified race as a social system that differentiates and classifies individuals into fixed categorical groups by identifying innate physical similarities and inferring “immutable” internal characteristics (Kosek 615). From our youth, we are socialized to attachspecific values and norms to various ethnic and racial groups. As we internalize the views of those with whom we interact including our parents, teachers and friends, we ultimately come to generate minimal, highly fragmented and stereotypical images of each race. These images act as the foundation to cultural understanding, further building on the experiences that we have had with a few membersof those “groups”.

As mentioned by the participants of the documentary Between: Living in the Hyphen, despite the fact that there is more widespread cultural acceptance in the current age characterized by diversity, multiculturalism and globalization, there is also a marked persistence to divide and segregate people into factions on the basis of physical traits and cultural backgrounds. These racial distinctions are reinforced, advanced and perpetuated informally and intentionally- but they may also be done through official documentation: including customs forms and in the national census of Canada.

Personally, each time that I fill out these forms, I am reminded of my Latino heritage, my inalienable belonging to this group, as well as the expectations of belonging to that community, never mind that I haven’t lived in the country in the past 7 years and no longer see myself as possessing many of the distinguishing cultural values and characteristics associated with Latino culture. While such details of the legal infrastructure are essentially included to monitor and eliminate racial discrimination and not with the purpose of enhancing racial barriers, they remind us that we live in an “either/or” world, as suggested by the individuals in the documentary. It is assumed that we if we look a particular way or have a certain surname, we must descend from a common and uniform ancestry. With the exception of the tiny “Other” section in these official forms, no space is made for inbetweenness or to account for individuals with “blended” origins. The participants in the documentary, in addition to Fred Wah’s family tree, are a testament to the fact that with each generation, racial identifications are becoming more convoluted, signaling the need to alter our perspectives on race. Returning back to the original question, perhaps it is necessary to see race as an evolving process…yet could this ever exterminate our view of race as an axis of difference? Is this even an achievable goal?

Works Cited

Jake Kosek (2009). “Race.” In Derek Gregory, Ron Johnston, Geraldine Pratt, Michael J. Watts, and Sarah Whatmore, eds., The Dictionary of Human Geography, Fifth Edition. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Thanks for this intriguing post! You bring up some interesting ideas here, such as that perspectives of different races have changed over time. This means that there is a still a chance of race being less of a “axis of difference”, as you call it, and will allow us to take further steps to making the treatment of each person equal, no matter their race. Personally, I don’t think race “biases” can ever be fully eliminated. However, steps can still be made.

Also, relating back to your point on how through children’s interactions with their parents and teachers, they gain “fragmented and stereotypical” views of race, I think this relates a bit to my post. I found an article on mixed race people and their experiences in society. Many of the people who were some percentage of African American, for example, even if they were only 25%, were seen as “black.” Just because they had darker skin. In today’s society, so many people make huge assumptions just by looking at the color of a person’s skin. There was one boy featured who was half white and half black, and had completely blonde and hair light skin. Looking at him, it would be very difficult to tell he is half black. Therefore, he probably gets treated very differently than someone who is also half black but shows it on the outside. This, I think, is completely unfair. And it just shows, that with a world becoming more and more multiracial, this categorization and unfair treatment of different races needs to stop.