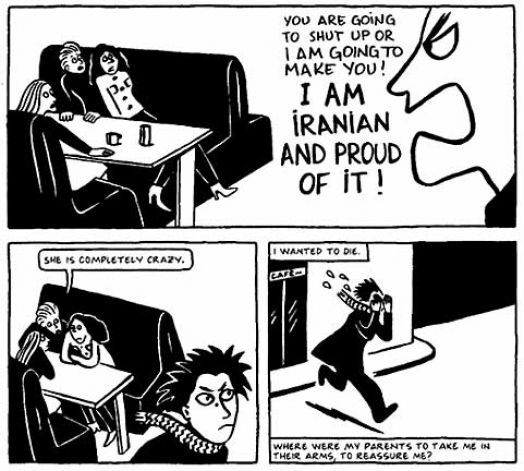

In ASTU class, our studies have primarily focused on minority narratives, such as the Iraq war blogs written by Pax and Riverbend, Persepolis and What is the What. However, for there to be minority narratives, there must be the existence of dominant voices, and I will look at some of the voices from the majority.

At the beginning of this year, YouTube was caught up in the “Draw My Life” video tag. Basically, YouTubers are encouraged to draw and narrate their lives, compile it into a video, and post it for others to see. These videos establish a common ground for YouTube community members to interact and relate better with one another. Since then, many YouTube celebrities have created their own videos, which have been received quite positively by their audience. See below:

The popularity of these “Draw My Life” videos illustrates a couple of things:

- YouTubers love knowing more about YouTube celebrities

- Story telling, especially personal story telling, “sells well” aka has great appeal

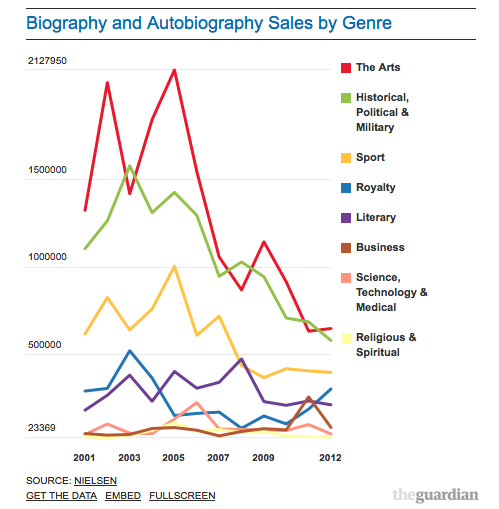

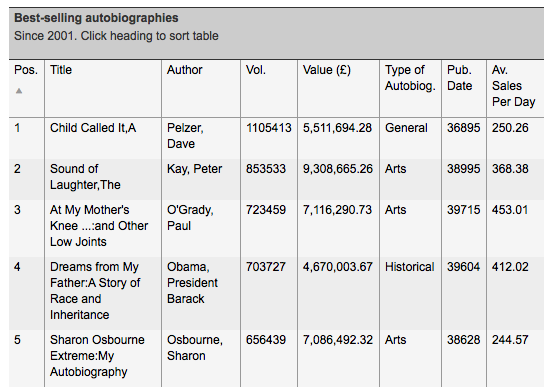

Taking a step back, we see that what happened on YouTube has also been happening in the “Western” world for a while now. Various celebrities have produced autobiographical films that have hit the big screens. One Direction’s This is Us, Justin Bieber’s Never Say Never and Katy Perry’s Part of Me are just some examples of films, regardless of if they are actually good or not, who can count on having a fairly large viewership.

Both the “Draw My Life” videos and celebrity autobiographical films function similarly in that their fans are able to learn more about their celebrity idols. In terms of “community building”, I think that YouTube is more successful in achieving this, as YouTube celebrities and users have a place to communicate, while viewing celebrity autobiographical films in theatres doesn’t really allow for much interaction. Furthermore, while these videos and films tell the stories of celebrities, I don’t think that they act as mechanisms for “bearing witness”, at least, not in the way we have been studying in class.

The narrative work we have looked at in ASTU class centre around the idea collectively bearing witness to trauma. Although the celebrities may have overcome personal struggles, their autobiographical work is still largely driven by other motives. Asides for building closer connections with their fans, I think that celebrities who choose to share a part of their already privileged lives through the media are driven by the promise of money, and an increase in fame. Quite different from certain minority narratives that try to offer alternative views to the dominant voices.

Of course, it would be a shame to not mention the autobiographical films that do try to bear witness. For example, the film, Gandhi, dramatized the life of Gandhi and depicted the struggles during India’s non-violent independence movement. One of the most memorable moments during the film was the re-enactment of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which served to bear witness to the violence and trauma experienced by civilians during the actual massacre.

Although it is a bit upsetting to know minority narratives are struggling to get noticed wile that dominant voices in life narratives consist of pop stars on tour, there is also work out, such as the film Gandhi, that are substantial and meaningful.