In our ASTU class, we recently finished reading Joy Kogawa’s novel Obasan, which looks at the traumatic treatment Japanese Canadians endured during World War II. The story is told from the perspective of Naomi, who is a Sensei, a third generation Canadian of Japanese descent. The story is portrayed through a web of flashbacks from Naomi’s childhood. Some of the factual details about the policies enacted during World War II surrounding the relocation Japanese Canadians are outlined in Naomi’s Aunt Emily’s diary, that is structured as a series of letters to Naomi’s mother. Aunt Emily is a fiery character, involved in social justice and concerned with remembering the past.

During our ASTU class we visited the University of British Columbia’s Rare Books & Special Collections and University Archives and looked at the Joy Kogawa Fonds. A recurring theme in several of the documents was strong feelings about the character of Aunt Emily and the letters that made up her diary. Although, many of these reviews were written in regard to earlier drafts of the book, meaning I am unaware of what Kogawa may have changed in Obasan before it reached publication, they do still give us an idea of some of the early reactions to the book.

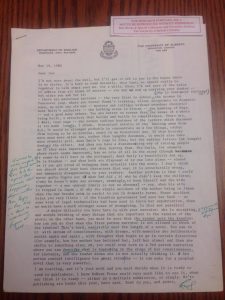

In a set of editorial notes, one reviewer is especially critical of the character of Aunt Emily, who he refers to as E. At one point he says, “E is for me the least real & convincing character in the story. Even her name bothers me” (Picture 1). He goes on to say that “Most of this is lovely — though E, still annoys. Do we need her here? Can we just omit her name?” (Picture 1). The author of the editorial notes does not give concrete reasons why he dislikes Emily, simple makes clear that he finds her annoying. Whether consciously or unconsciously, his dislike of Aunt Emily may stem from the discomfort she makes him feel. Unlike Obasan and Naomi, who are happy to let the past remain in the past, Aunt Emily is obsessed with preserving the past because, as she says, “The past is the future” (Kogawa 51). She likes to push the past into people’s faces, as she often does to Naomi by physically pushing documents under her nose. The past is rarely pleasant or pretty. It is easier to not talk about it because of the discomfort it makes people feel. Yet, by not talking about the past we are more likely to make the same mistakes again.

The idea of silencing is central to the novel. Omitting the character of Aunt Emily, which this reviewer would probably like to see, would itself be an act of silencing. It would be the loss of a means of presenting information about the past for the sake of comfort. The attitude of the reviewer is an excellent example of the attitudes Kogawa seems to be challenging by writing Obasan. Obasan is about telling the dark and difficult stories that often make people uncomfortable, but are still a critical part of Canadian history and a crucial part of building Canada’s future.

In a different review of the book, from someone at the Department of English at the University of Alberta, we see that Aunt Emily’s diary of letters also faced scrutiny. This reviewer said that “There are I feel real sags — the rather tedious business of the letters which document at too much length, I think, historical details of the hauling away from B.C.” (Picture 2). Viewing historical details from the major disruption of the lives of thousands of Japanese Canadians as tedious is culturally and historically insensitive. This view also causes me to question why these details seem so tedious. Perhaps, being forced to acknowledge the atrocities that the Canadian government subjected its own citizens to causes too much unease. Yet, trying to ignore that which makes us uneasy does not make it go away; it simply allows the root of the problem, which in this case is prejudice and racism, to fester.

Another key role of Aunt Emily is to present a different emotional response to dealing with trauma. Where Obasan and Naomi feel that it is too painful to relive the past and that it will not change anything, Aunt Emily rages against injustice, a whirlwind of energy and anger. The same reviewer from the editorial notes says at one point that “she complains too much,” (Picture 3) referring to Emily. This is extremely insensitive considering that the treatment that Japanese Canadians endured justifies any amount of complaining. Although it may be painful to relive the past, not acknowledging it allows the past to be buried, creating the danger that it can be repeated. Being angry, being annoying, refusing to be silent forces people to acknowledge the prejudice interwoven in Canadian history.

Through these historic documents, that represent early reactions to Obasan, we see people’s discomfort when being forced to acknowledge the past. This discomfort is not directly stated but hinted at through disapproval of Aunt Emily and the letters she writes. Towards the beginning of the book, Naomi asks, “If Aunt Emily with her billions of letters and articles and speeches, her tears and her rage, her friends and her committees – if all that couldn’t bring contentment, what was the point?” (Kogawa 50). The point is that without such efforts, fighting to remember the past is seen as complaining too much and fighting against injustice is seen as an annoyance. The point is that covering up the unpleasant parts of the past increases the likelihood of repeating the same atrocities.

Bibliography:

Kogawa, Joy. Obasan. Anchor Books, 1994

All pictures were taken at the University of British Columbia’s Rare Books & Special Collections and University Archives.

Picture 1:

Picture 2:

Picture 3: