For this blog assignment, I have chosen to collect my thoughts and opinions regarding the Indian Act of 1876, and whether or not my findings support Colemans argument about his project on white civility. To start the blog, I will state my current opinion – which is that based on my current knowledge on the Indian Act and what it stood for, I believe that this governing activity does absolutely support Coleman’s findings. Coleman argues that throughout time, Canadian policies and governing bodies have consistently created a white, Christian society that has mimicked a form of British civility. This can be seen throughout the various policies that have been implemented throughout Canada’s history, where many cultures and people of different beliefs and values were excluded or told to assimilate. In this sense, state legislation and policies have worked towards creating nationalism within the country that mimicked British colonial civility, leading to an accepted ‘English-Canadian’ whiteness.

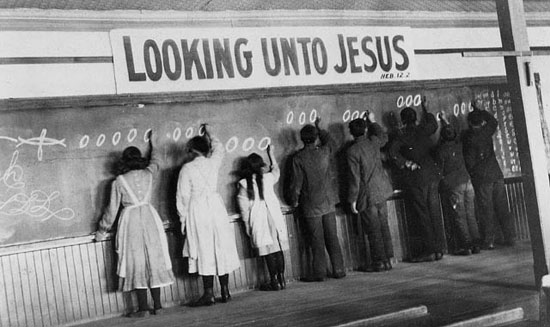

The Indian Act in particular, was established in 1876 with the goal of assimilating the Aboriginal population of Canada into westernized culture. Different aboriginal groups were represented by the Minister of Indian Affairs, who would designate how much land each band could use. The land technically belonged to the Crown, who would create Reserves in order to call the land as being ‘set aside’ for the use of a Band of Indians. Furthermore, officials and government personnel under the Crown deemed many aboriginal customs and cultures as unsuitable and ‘uncivilized’. In order to bypass that, many traditions such as the Potlatch and the Sundance were deemed to be illegal. Legislations such as these, where bands are unable to practice their culture and heritage further shows evidence of Colemans theory, that clearly the different views of the natives did not fall into the settlers view of British civility. In general, the theme of the Indian Act was to promote civilization and assimilation within the Indians. The notion of each Native as being required to register for a Native status was viewed as a necessary, temporary stepping point in order to reach full assimilation into the already defined civil views of the nation. This nationalist movement aimed to remain as close to Britain as possible. Many techniques and strategies were used in order to promote integration, such as opening the Residential School System. This system became mandatory for all Native children to attend, where they would be taught the ways of civility by being forced to reject their own language, beliefs, and customs. The children were told that their culture was dirty and wrong, and that they needed to change into the westernized view of the world. A well-known slogan for the Residential Schools was to ‘Kill Indian, Save the Man“.

Besides the Indian Act, anything but the white English settler was seen as perverse and unsuitable for the land. Immigrants, Aboriginals, and anyone that was not from British civil origin were expected to assimilate into the white ideal of British civility. Anything but was seen as less worthy.

Citings:

“Residential Schooling”. Multimedia Resources. “http://www.swlauriersb.qc.ca/Schools/ltm/multimedia/2013_e-portfolios/ALANA%20website/My%20Web%20Sites/residentialschool1.jpg”. Web. March 21. 2014

“Residential Programs and Indian Act”. Umista. “http://www.umista.org/collections/Web. March 21. 2014

Hi Anna,

Loved your post, I enjoyed how you touched base on the land being distributed to Aboriginals, via The Indian Act, belonging to the Crown. I can never get over how the colonizers came to Canada and poached the land from the Aboriginal people, then essentially distributing (their own land) back to them in patchwork or Reserves. What’s worse is that the majority of the time colonizers and the Crown allocated the worst type of land to Aboriginals and kept the most valuable land for themselves. The fact that Potlach’s were deemed illegal after the Indian act is pretty alarming; I believe by not allowing Aboriginals to gather and perform their ceremonies was most damaging to them as a people. Interestingly enough, today variations of Potlach’s are widely performed within Christian churches.

-Sam

Heres a link regarding Christian “Potlucks”:

http://christianity.stackexchange.com/questions/15083/what-is-the-origin-of-the-church-potluck

Hi Sam – ummmmmm, church potlucks and The Potlatch are not the same thing

Yes, it is different.

From what I understand, the native potlatch is a ceremony where gifts and goods are redistributed back to the people. It’s a ‘gift-giving’ ceremony, where people shared their goods and accumulated wealth. A type of economy. When the colonists came, they were distressed at this type of distribution and felt it was primitive. In their eyes, what kind of sane person would give away almost all their hard earned possessions?

When you described the colonial attitude of young Canada as “English-Canadian” it reminded me of a trilogy of Canadian novels written by Canadian author, Kit Pearson called the War Trilogy. I read the series as a child (they’re kid’s books) about a little English girl who travels to Canada with her little brother during WW2 to escape for the duration of the war. Interestingly, I don’t recall any mention of First Nations cultures in the storyline even though Norah (protagonist) goes in to a fair amount of detail about the Canadian landscape, education system, and culture. Of course as a product of the “English-Canadian” nationalism project I, as a white English-speaking Canadian would not notice the now-glaring hole in Norah’s “Canadian” experience while I was a child going through the Elementary school system.

What is disturbing about Norah’s storyline is the fact that she lives right in the middle of the severest implementation of the Indian Act. Residential schools were in session (and continued almost until the time I was going through elementary school in the 1990s), Potlatches were banned, regalia was stolen, First Nations people were imprisoned for possessing their cultural objects. It’s scary to think that Norah’s experience as an actual immigrant (maybe vistor is a better word? She was in Canada for 5 years) garnered her more respect and kinder treatment than the people who have occupied this land since the world was created, regardless of creation story.

Thanks for the post, Anna. It gave me a feeling of childhood nostalgia (even though I may critically question cultural absences now, I really did (do) love those books!) and allowed me the opportunity to consider the lasting impacts of the Indian Act on both First Nations people and my own educational experience. It frustrates me that I was not exposed nor taught about these issues as a child.

Hi Anna, some provocative images here, thanks. I do wish this post had some citation though? The link to the U’mista Cultural Society in Alert Bay is interesting, and relevant – but who else are you citing? A couple of things stood out for me, one is the suggestion that “different aboriginal groups were represented by the Minister of Indian Affairs, who would designate how much land each band could use”. Is “representation” right word here? That would imply the First Nations peoples were being politically represented, they were not; they could not vote as First Nations, in order to vote they had to resign their status as an “Indian.” Instead, the Indian Act legislated and governed the lives of First Nations with out representation. One other note, it would be good to use quotation marks with the word “band” when referring to First Nations today. You inspired some good insights from Jessica – thank you.