——————————————————————————————————-

“Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew. Agitator, activist, artist… writer, curator, thinker. Words that describe, but never really catch the spirit of the man until we add one other, Aboriginal. His thinking, his way of being, his art making was always informed and animated by Aboriginal philosophies, and customary ways of knowing. Far from being a dogmatist though, his was an Indigeneity of thought, of intellectual and cosmological manifestation. With the rise of the inclusion of Aboriginal artists in institutional arts programming in the past twenty years, there has been increased dialogue around the nature and political/cultural imperative of Aboriginal arts presentation and discourse. Ahasiw was on the front lines of these struggles throughout his career. Not just as a thinker and writer, but actively mobilizing ideas of Aboriginal cultural sovereignty and self determination through his tireless policy and theoretical work”

-by Kanien’kehá:ka author Steve Loft, from http://ghostkeeper.gruntarchives.org/essay-for-iktomi-steve-loft.html

——————————————————————————————————–

“Ahasiw is not uncritical of the web. Moreover, he wonders how Native people can make the web, at least part of it, truly Aboriginal . Is it possible to bring a spirituality, an ethicality, an aesthetic”.

-Skawenneti Tricia Fragnito speaking about Cree/Metis artist Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew’s gallery space in her project CyberPowWow2k , retrieved from http://www.cyberpowwow.net/STFwork-ami.html

——————————————————————————————————–

“It’s the web that holds us together,” Iktomi explained to me, “in the past, in the present, and in the future.”

– Kanien’kehá:ka author Steven Loft, from http://ghostkeeper.gruntarchives.org/essay-for-iktomi-steve-loft.html

——————————————————————————————————–

I sat down to write a blog post about my close reading of Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew‘s 1996 project Isi-pikiskwewin Ayapihkesisak, and I found myself unable to stop exploring his world, his web. Since I first engaged with this piece last year I have been unable to close that computer tab. I can’t un-do my on going experience of this piece, not do I ever want to. I try to cross reference Isi-pikiskwewin Ayapihkesisak with my Cree language dictionary coupled with the site: ‘Ghost keeper’ which is a “comprehensive look at the work of Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew”, and still I am no closer to a reading. And nor should I be. What Ahasiw created is an incredibly powerful interactive, and interconnected web based portal intentionally and carefully weaving together various Indigenous multi media artists and art forms with a focus on nehiyawewin culture, language and worldview, as well as speaking to issues of urban Indigeneity in the DTES of Vancouver along with profound work relating to systemic racism and settler colonialism. His web extends far beyond the ‘world wide’, drawing on nehiyawewin world views, cosmology and protocls, while fiercely challenging the stranglehold of ‘new’ media that settler colonialism desperately clings to. Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew work leaves me speechless, every time.

I would very much like to continue reading and researching the ways in which Ahasiw chooses to use nehiyawewin within Isi-pikiskwewin Ayapihkesisak. But that is a larger project for a larger day. For now I will say this, I feel Ahasiw’s choice to include nehiyawewin within his piece Isi-pikiskwewin Ayapihkesisak is an incredibly powerful articulation of visual sovereingty, as it unavoidably determines and positions an Indigenous space through language. By weaving nehiyawewin into very crucial points of the site, Ahasiw immediately pushes against Canadian settler colonialism. As well, since nehiyawewin frames this site from the very beginning, with the site’s tab reading ‘tansi’ as well as immediate sound clips playing as soon as you open the site, along with the visual presence of written nehiyawewin in the site’s the title,

Ahasiw strongly affirms this experience runs much deeper than what would be defined by a Western construct as simply ‘art’. As Kanien’kehá:ka author Steven Loft articulates in his essay Aboriginal Media Art and the Postmodern Conundrum: A Coyote perspective , “Indigenous ‘art’ is much more a function of remembering ,the creation and articulation of cultural memory” ( Loft 2005).

Isi-pikiskwewin Ayapihkesisak was released the same time the last residential school was closing in Canada. The system of “killing the Indian in the child” attempted to eradicate all Indigenous languages. By choosing to include nehiyawewin words and ideas into the title, and menu function of the site, it immediately and urgently affirms and positions the type of space you are entering as a visitor is not neutral. I would argue the use of nehiyawewin serves as a means to negotiate Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew‘s space as an articulation stemming from the framework of visual sovereingty, and that by entering you acknowledge you are a guest with responsibilities to not only respect the stories and knowledge shared but to yourself ,work to understand the history of resilience that informed the work.

![]()

—————————————————————————————————————————–

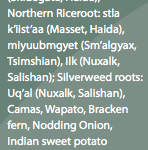

some nehiyawewin glossing:

some nehiyawewin glossing:

wici-one noun=of his or her own kind, verb= together with

wicihito=verb, to help

connects to the ‘how to’ page of the site

kinina-naskom-itin=thank you, I am grateful to you, to be thankful, to speak words of thanks

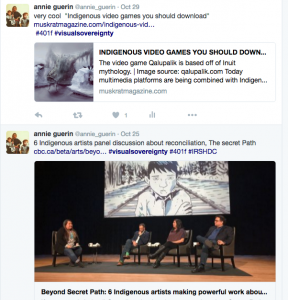

In this post I will be looking at further examples of visual sovereignty as well as issues raised of visual sovereingty specifically in the wake of Canadian rock star Gord Downie’s multi media project “The Secret Path“. (Downie 2016).

—————————————————————————————————————–

“Today sovereignty is taking shape in visual thought as indigenous artists negotiate cultural spaces”

–Jolene Rickard

-A Tribe Called Red, Stadium Pow Wow Ft.Black Bear, We Are The Hallucci Nation, 2016.

—————————————————————————————————————–okay, so here it goes.

This past week I have been thinking a lot about the attention Gord Downie’s, at times unsettling multi media project, “The Secret Path”, has gotten in Canadian mainstream culture. I say unsettling because he is a dying white rock star, and Canadians are somehow put at ease that he is the one telling the story of Indian Residential School System. Its fucked.

In Downie’s viusal album he sings the story of Chanie, or ‘Charlie’ Wenjack, a 12 year old Ojibwe boy who died while trying to walk home to Olgoki, Ontario from residential school. At the one hour mark of the above CBC video link, “The Road to Reconciliation: A Panel Discussion about The Secret Path” was also live-streamed the same night the film was premiered. In this panel discussion, Ry Moran, the Director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation; Tasha Hubbard, filmmaker and assistant professor at the University of Saskatchewan; and Jesse Wente, CBC broadcaster and Director of Film Programmes at TIFF Bell Lightbox addressed their reactions to Gord Downie’s film, the history of the Residential school system, and spoke to six Indigenous artists;

Tanya Tagaq

Alanis Obomsawin

A Tribe Called Red

Article 11

Kent Monkman

Joseph Boyden

who the panelists think have made, and continue to make important work that Canadians should know about. The reason I wanted to address this particular project, in this particular blog post, is simply because I found the way in which Indigenous visual sovereignty was articulated in this panel discussion , (i.e, through the acknowledgment that Indigenous artists have been telling stories of the Residential School System, since the beginning, and accepting that it seems Canadians need a ‘Gord Downie’, to acknowledge the history they feel too uncomfortable to learn) an incredibly interesting intersection. And through this safe white lens that has historically attempted to erase and silence this history , the panelists along with the Wenjack family, are brilliantly calling attention and articulating visual sovereingty. As Kristen Dowell speaks to in “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World” in Sovereign Screens: Aborginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, 2013, “Speaking back to the legacy of misrepresentation in dominant media is an act of cultural autonomy that reclaims the screen to tell Aboriginal stories from Aboriginal perspectives” (Dowell 2013). So through a potentially problematic production of Indigenous experience, the panelists and the Wenjack sisters are turning it right around and determining a sovereign space for Indigenous voice. In no way am I dismissing the resilience of the Wenjack family and their work in making this story come to life, but I am concerned in how deeply disconnected the dominant Western construct is from the history of the Residential school system. Jesse Wente spoke to the way in which Indigenous artists have been telling this story and stories like it for a very long time, and how “Canadians don’t have a history of listening to Indigenous peoples…so maybe Canadians need someone like Gord Downie to tell them this story for them to pay attention, perhaps this piece will make the path to Indigenous artists less obscure” (Wente 2016). As well, panelist Tasha Hubbard spoke to the way this film will hopefully inspire Canadians to learn the history of the residential school system, and how as little as 40% of Canadians even know what the the TRC actually is, let alone the 94 calls to action.

In the end of Downi’e visual album, he is filmed talking with Charlie Wenjack’s four sisters. Pearl, one of Charlie’s sisters says ” You know, as big as the world is, we are all connected in some way, I don’t know how, but I know that. You can be connected to somebody almost like a sister and a brother. I think thats why Gord was connected to Charlie” (Pearl Wenjack, 2016 http://www.cbc.ca/beta/arts/beyond-secret-path-6-indigenous-artists-making-powerful-work-about-reconciliation-1.3819324). So perhaps the Wenjack family nominated Downie to tell Charlie’s story. Downie’s empathetically fleeting role in Canadian pop culture, becomes the medium through which the Wenjack family articulate the continuation of their visual sovereingty, and call attention to their aim of ensuring every reservation in Canada has a high school. So although Downie’s album, film, or tour are not acts visual sovereignty, as he is not Indigenous, he does support the articulation of “Aboriginal peoples’ distinct cultural traditions, political status and collective identities, through aesthetic and cinematic means”(Dowell 2013). Downie’s work helps to gain Canada’s attention to acknowledge Indigenous presence in Canada, and helps support Indigenous visual sovereignty. As Wente says, “if it takes a white rock star, then it takes a white rick star and I applaud him” (Wente http://www.cbc.ca/beta/arts/beyond-secret-path-6-indigenous-artists-making-powerful-work-about-reconciliation-1.3819324)

—————————————————————————————————————————–

The ways in which visual sovereingty are articulated and consumed are intentionally not always obviously visual. Historically/ neo-colonially, oppressive Canadian legislations have attempted to ban Indigenous communities from practicing their culture, food sovereingty, parenting, teachings, laws, resource management systemes, and languages. But not being able to see visual sovereingty doesn’t mean it ceases to exist. As Kristen Dowell says, “Given the history of the administration of Aboriginal lives through bureaucratic regimes- the reserve system, residential schools, and the Indian Act- Aboriginal media can speak back to this legacy by reclaiming the screen through acts of Aboriginal visual sovereignty”. (Dowell 2013). If anything, visual sovereingty is an ever growing framework as a direct result of the reliance of Indigenous communities continued practice of their distinct culture and languages. As we saw in “The secret Path”, the spaces and interconnections created and enacted through and by visual sovereignty are not necessary strictly visual. We don’t directly see Pearl Wenjack telling her brother’s story. Nor do we explicitly see her tell of her aim to have every reservation in Canada equipped with a high schools, but we do see her expression and representation of visual sovereingty through Gord Downie.

#visualsovereignty

Kwakwakawak’w carver Ellen Neel, her husband Ed, and Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis Chief William Scow, coming to UBC in ceremonial clothing, in a group of three or more to gift the Thunderbird crest named “Victory Through Honour” to UBC, that they made an incredibly powerful act of visual sovereignty during a time that ceremonial regalia, a Potlatch gathering in which political decisions were made, and groupings of three or more Indigenous peoples in one place, were all denied by the Canadian government.

—————————————————————————————————————–

‘An “unapologetically Indigenous” generated radio podcast’ , OTIPÊYIMISIW-ISKWÊWAK KIHCI-KÎSIKOHK ( Metis in Space), is another example of visual sovereignty that is not always consumed solely through a visual means. The above soundcloud link to Metis in Space is offered through a mobile or computer screen, but all that is seen is the sound wave graphed out across time. Visual sovereignty extends far beyond the spaces we can see with our eyes. I really enjoy what Tuscara artist and scholar Jolene Rickard said in regards to visual sovereingty as quoted in Kristen Dowell’s work Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast ; “Today sovereignty is taking shape in visual thought as indigenous artists negotiate cultural spaces”(Rickard 1995).

The other day I was listening to the Edmonton based radio station CJSR’s, show Acimowin,

in which the host JoJo on the Radioh, spoke with my absolute favourite author Richard Van Camp along with Metis in Space hosts Molly and Chelsea. As I was listening to the live stream of the show through my computer, I understood the show was determining an Indigenous space within the world of radio. And although not necessary visual in the sense of an actual aesthetic, the show was creating/reimagining/reclaiming/reorganizing an Indigenous determined space and articulating visual thought.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

For me, I understand and use the concept of visual sovereignty to acknowledge and support cultural spaces made/reimagined/reclaimed/determined by Indigenous people and Indigenous generated content. I do this acknowledgement primarily through my twitter account with the use of the hashtag #visualsovereignty.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

In Kristen Dowell’s book, Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast (Dowell 2013), Dowell uses the term Visual Sovereignty” as the articulation of Aboriginal people’s distinctive cultural traditions, political status, and collective identities through aesthetic and cinematic means”(Dowell 2013). Further explored, Dowell’s use of visual sovereignty, originates from Tuscarora artist, author, researcher, curator and professor, Jolene Rickard, who coined the concept to describe “sovereignty taking shape in the visual thought as Indigenous artists negotiate cultural space” (Rickard 1995). Rickard wrote this in the mid 90’s, when a) the last residential school closed, and b) un-coincidently, a very powerful movement of Indigenous new media projects and programs like Mohawk artist Skawennati Tricia Fragnito, along with Chereoke digital artist and founder of Obx laboratory, Jason Lewis created and curated CyberPowWow. This project was part virtual gallery, part chat space, and above all else “ an Aboriginally determined online gallery to propose Aboriginal Territories in cyberspace” (Lewis and Skwennati 2005). The site intended to overcome stereotypes of Indigenous peoples as well as help generate “critical discourse-both in person and on-line- about First Nations art, technology, and community” (Skawennati and Lewis 2005).

In Rickard’s article“First Nations Territory in Cyber Space Declared: No Treaties Needed” she addresses the power of the CyberPowWow project as it “represents the desire by both the participating artists and organizer to reconfigure Indian space. The 1800’s represented the timeframe when Native nations lost nearly eighty percent of our landbase to Canada and the United States. A counter strategy to the governmental suppression of large Indian gatherings (remember the Battle of Little Big Horn) was the formation of the “pow wow” event. Various First Nations song and dance traditions from across the Plains were shared intertribally, primarily to give thanks and to also assert their continued independence”.

–Jolene Rickard, “First Nations Territory in Cyber Space Declared: No Treaties Needed”

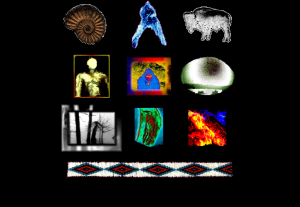

The same year that CyberPowWow was released into the world, Cree/Metis artist Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew’s, awe inspiring spider web based, inter connected world isi-pîkiskwêwin-ayapihkêsîsak was also released.

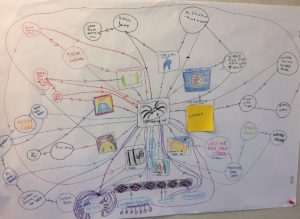

Our class had the pleasure of visually mapping isi-pîkiskwêwin-ayapihkêsîsak, which only further affirmed Iskwew’s brilliance and fiercely unique expression of visual sovereingty.

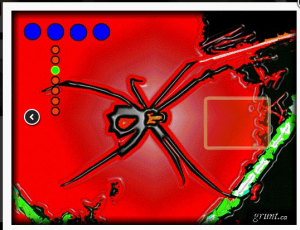

Iskwew also participated in Skawennati and Lewis’ CyberPowWow2k through designing rooms such as “AMI Blood Widow”

http://ghostkeeper.gruntarchives.org/images-cyberpowwow.html#lightbox

http://ghostkeeper.gruntarchives.org/images-cyberpowwow.html#lightbox

“AMI_Blood_Widow” depicts a black widow spider, all shiny and scary and futuristic. The room is a nod to Isi-pikiskwewin Ayapihkesisak (Speaking the Language of Spiders), his deep and powerful art and poetry website. It also refers to the Cree creation story (which can also be found at that site).

-Skawenneti Tricia Fragnito speaking about Cree/Metis artist Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew’s gallery space in her project CyberPowWow2k , retrieved from http://www.cyberpowwow.net/STFwork-ami.html

In a write up about Iskwew, Skaeennati had this to say;

A Chatroom

is Worth

a Thousand Words

“The room states that we need to believe in our own metaphors. When I asked him why he’d made so many rooms, he said, “They form a constellation that attempts to tell one complex story. There is a desire to say things in a more complete way, to leave a legacy” ” (Skawennati, Iskwew, http://www.cyberpowwow.net/STFwork-ami.html)

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew’s, isi-pîkiskwêwin-ayapihkêsîsak to me represents the most powerful new media articulations of visual sovereingty I have ever had the privilege of interacting with. I was especially blown away by Iskwew’s use of nehiyawewin to represent not only his Cree world view, but to also reshape, recode and redesign new media work form an entirely Indigenous lens. The entry into the site is not in English and immediately confirms the presence of Indigenous political autonomy, and activism. The western construct of the internet is completely and utterly reimagined through Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew work. As well, by having the title, acknowledgments, and ‘how to’ all expressed in nehiyawewin, Ahasiw is acknowledging the importance and continued resilience of Indigenous communities in practicing their languages against all oppressive Canadian legislations. The core make up of the site is framed through nehiyawewin concepts. I find Ahasiw’s deliberate and detailed use of nehiyawewin in Isi-pikiskwewin Ayapihkesisak an incredibly powerful and foundational articulation of visual sovereignty within digital new media. Not only do the nehiyawewin words express a distinct Cree culture, and worldview, they also acknowledge Indigenous resilience of langauge, and express and negotiate a distinct Indigenously determined space, through aesthetic means. (Dowell 2013).

—————————————————————————————————————–

resources:

- AbTeC – About. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from http://www.abtec.org/index.html

- A Tribe Called Red – A Tribe Called Red. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from http://atribecalledred.com/

- What is CyberPowWow? (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from http://www.cyberpowwow.net/about.html

- Artists. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from http://www.spiderlanguage.net/domainsecond.htm

- The Work of Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016 from http://ghostkeeper.gruntarchives.org/index.html

- Home. (n.d). Retrieved November 04, 2016http://www.obxlabs.net/.

- Secret Path. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from http://secretpath.ca/

- Métis In Space. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from http://www.indianandcowboy.com/metis-in-space/

- Calls to Action – Truth and Reconciliation Commission of … (n.d.). Retrieved November 4, 2016, from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- Jolene Rickard. (n.d.). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from http://www.cyberpowwow.net/nation2nation/jolenework.html

- Sovereign Screens – University of Nebraska Press. (n.d.). Retrieved November 4, 2016, from https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/product/Sovereign-Screens,675764.aspx

- LeClaire, N., Cardinal, G., Waugh, E. H., & Hunter, E. (1998). Alberta elders’ Cree dictionary = Alperta ohci kehtehayak nehiyaw otwestamakewasinahikan. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

- Townsend, M. A., Claxton, D., & Loft, S. (2005). Transference, tradition, technology: Native new media exploring visual & digital culture. Banff, Alta.: Walter Phillips Gallery Editions.

David Gaertner

November 9, 2016 — 4:57 pm

There is a lot of very intriguing stuff going on in this post, Annie! I am very intrigued by the “collage” model you seem to be taking up here; the way your message is taken up in the medium. Is this, in its own way, a hommage to Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew? I wonder if it might work more effectively if each of these ideas had there own page on the blog and then were connected via hyperlinks? Perhaps something to think about.

David Gaertner

November 9, 2016 — 5:00 pm

Thank you also for your reflections on Downie’s work, an issue I have been grappling with myself. I think screen sovereignty is a very productive way to think this work through. Is the Secret Path screen sovereignty? I am inclined to say no. But there are some pretty serious implications that come with that, which you help to address. Good work.