I wanted to share, reflect, and build on some of the work I am doing for a final project in Daisy Rosenblum’s FNEL 381 course, Bio-cultural Diversity: Language, Community, and the Environment, as I feel it very much connects to themes of visual sovereignty explored throughout our term, as well as something I am currently working to remediate into a podcast

————————————————————————————–

“The Indigenous Peoples’s ethnocides being brought about by international media, sciences, trade, colonialism, and world religions-generating a “monoculture of the mind” are documented in the United nations Environmental Program’s publication. Cultural and spiritual Values of Bio-diversity…..”warning that ‘traditional’ can imply restrictions of the Convention on Biological Diversity, only to those embodying traditional life-styles, preted to mean ‘frozen in time’...yet it is the traditional methods of research and application” not just particular pieces of knowledge that persists in a ‘tradition of invention and innovation”

-Ahasiw Maskegon-Iskwew Drumbeats to Drumbytes:Globalizing Networked Aboriginal Art from “”Transference Traditions Technology: native New media Exploring Visual and Digital Culture.” 2005

————————————————————————————–

This year I have been thinking a lot about a way I could work to connect Indigenous food sovereingty to that of visually sovereignty, with a focus on Indigenous languages. Throughout this work, I began to reflect on my education in the field of ‘natural nutrition’, a field I had studied and worked in for the 5 years before beginning my time at the U of A, and later UBC. I thought I was doing exactly what I was good at, but when I finished the program I felt ashamed and in much more need of an un-learning than when I had began. I wasn’t able to name it back then, but I can now, I felt what we were being trained to do as natural nutritionists, focussing on medicinal plant knowledge, was very much perpetuating an incredibly problematic colonial construct. The knowledge we were given was systematically void of any Indigenous acknowledgement. And as Iskwew speaks to in the exert above, that systemic colonial construct is continually attempting to erase Indigenous knowledge and experience, whether through media, science, or I would also argue healthcare, and more specifically a Western approach to ‘alternative medicines’. I was reminded of kwakwaka’wakw scholar and author Sarah Hunt and her words from the podcast Decolonizing the Roots of Rape Culture, in which she says “colonization is a structure not an event. Meaning colonization didn’t just happen 150 years when Canada was imposed here in stolen lands but that colonization is embedded in the socio-political structures through which settler nations continue to be produced. Yet these structures of power are not only embedded in law and governance and policy, but the everyday actions of you and I in which the norms of settler colonialism are reproduced.” (Hunt 2016). The danger that lies within institutions to perpetuate a colonial construct is not at all surprising, but it is something that many Indigenous health care practitioners are working to stop.

My Inspiration for this project came from an event I attended earlier this year called

Nәćamat: 2016 Downtown Eastside Aboriginal Women’s Village of Wellness

The First Nations Health Authority, which put on the event works to “support BC First Nations individuals, families and communities to achieve and enjoy the highest level of health and wellness by: working with them on their health and wellness journeys; honouring traditions and cultures; and championing First Nations health and wellness within the FNHA organization and with all of our partners…We are here because of those that came before us, and to work on behalf of First Nations. We draw upon the diverse and unique cultures, ceremonies, customs, and teachings of First Nations for strength, wisdom, and guidance. We uphold traditional and holistic approaches to health and self-care and strive to achieve a balance in our mental, spiritual, emotional, and physical wellness”. (FNHA 2016). The FNHA produced the First Nations Traditional Foods Fact Sheets, which were given out at the event and well worth a look through if you have the time.

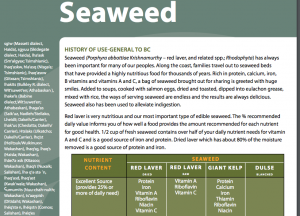

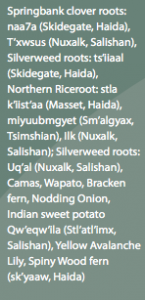

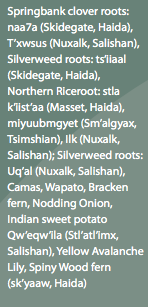

The fact sheets include knowledge of many traditional foods such as berries, salmon, Eulachon, seaweeds, deer, moose, bison, herring, clams, roots, birds, rabbit, and some medicinal plants, and the name of these foods is along the side of the individual fact sheets in many different BC Indigenous languages. The image below is from the roots fact sheet.

The fact sheets also tell the history of use-general to BC, along with traditional harvesting, traditional food use practices, nutritional information, as well as a separate sheet outlining recipes for some of these various traditional foods. As Iskwew spoke to in his article above, The FNHA’s use of the term ‘traditional’ in relation to foods and medicines, doesn’t mean a thing of the past, the fact sheets are aesthetically produced in a way that speaks to Indigenous cultural tradition as an act of protocol, or harvesting, gathering and preparing, and does so in a powerful act of visual sovereingty. And as Kristen Dowell speaks to in “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World” from her book Soverign Screens:Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast, about screen sovereignty which I think very much applies to the FNHA’s fact sheets, is how these works ” assert visual sovereignty by articulating the long standing connection that Coast Salish people have with the land in Vancouver and by repositioning Vancouver as an Aboriginal city” (Dowell 2013).

And after witnessing Tuesday’s awe-inspiring Indigenous new media, and Indigenous geographies sharing potluck, I was so deeply inspired to further connect, draw upon , and build on, my on-going academic work, and passions, in meaningful, creative and personal way. So here I go.

To begin with… For Daisy’s class, I am producing a small informative pamphlet outlining some of my research on the plant sc’òlseʔ( the nɬeʔkepmxcin word for the plant Tall Oregon grape. The pamphlet will be much like the FNHA’s fact sheets.

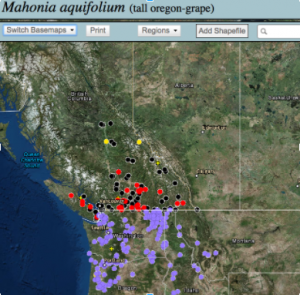

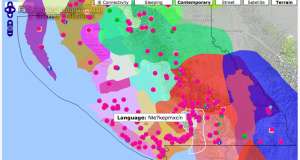

My research led me through a magnitude of various sources, but predominantly what was available online, was that of a colonial lens, continually attempting to silence Indigenous presence through a multitude of media platforms such as maps, or scientific vernacular. If one was to look up ‘Oregon grape’ they would understand that it grows throughout B.C and Oregon, and is good to treating a number of health concerns. As shown in the map below, the plant is placed and restricted by colonial boarders, void of any Indigenous acknowledgement presence, territory, nations, language, or life.

*Photo curtesy of UBC geography.

“Our Elders nurtured the important cultural traditions against tremendous odds.”

-Doreen Jensen “Art history” in Give Back First Nations Perspectives on Cultural Practice 1992, from Dana Claxton’s article Re:Wind in “Transference Traditions Technology: native New media Exploring Visual and Digital Culture” 2005.

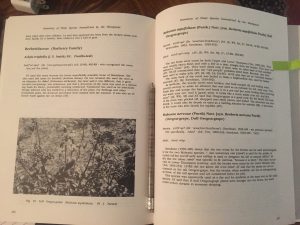

I then visited with Kim lawson over at Xwi7xwa and we found a lot of academic published books, mostly coming from western ethnographers and linguists.

————————————————————————————–

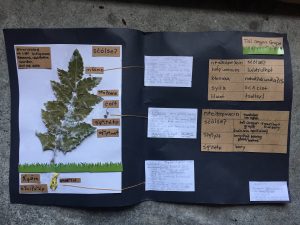

What I am focussing on for Daisy’s course project, is not only the Indigenous (hi)story of sc’òlseʔ as told through nɬeʔkepmxcin, but the enduring resilience of the nɬeʔkepmx elders who held and cared for that history against hugely oppressive legislations. Initially I spent some time at the Indigenous Research and Education Garden this past September, researching and collecting fallen samples of sc’òlseʔ. I then pressed the plant and made a presentation on my early stages of research.

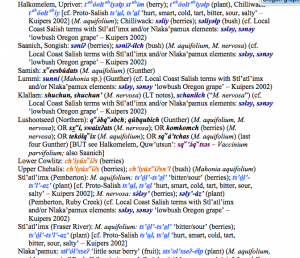

Looking at sc’òlseʔ as outlined in nɬeʔkepmxcin, the language of the nɬeʔkepmx people , I used a few key resources, one was Nancy Turner’s book “Thompson Ethnobotony: Knowledge and Usage of Plants by the Thompson Indians of British Columbia” (Turner 1990), along with James Teit’s book “Ethnobotany of the Thompson Indians of British Columbia” (1973).

A real interesting link is one of Nancy Turner’s appendices in which she has documented all the Indigenous Languages name for certain plants, so for Oregon Grape there are over 30 names from 30 languages, and something I will using to name the plant in Indigenous languages much like the FNHA’s fact sheet.

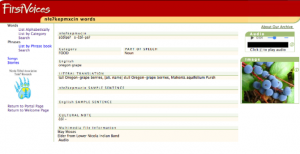

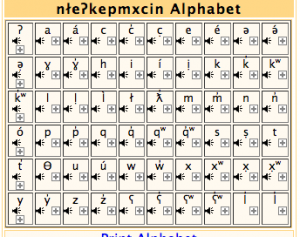

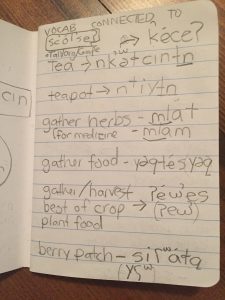

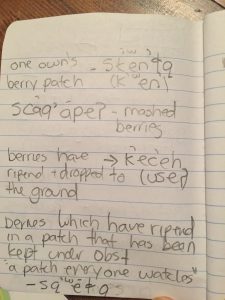

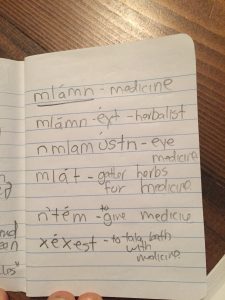

The reason I chose to research nɬeʔkepmxcin, is because I found the most comprehensive, available, and detailed resources on this particular language. I also spent hours getting lost in “Thompson River Salish dictionary: nłe?kepmxcín” by Laurence and Terry Thompson, found in special collections at the Xwi7xwa library. It was there that I began an inventory of nɬeʔkepmxcin verbs, lexical suffixes, anything relating to sc’òlseʔ which translates as sour or tart berry.

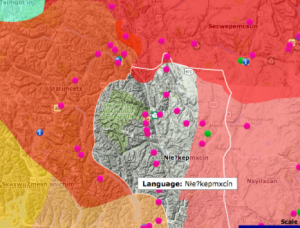

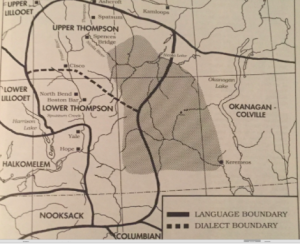

nɬeʔkepmxcin is spoken from Spuzzum to Lytton, along the Thompson River and into the Nicola valley.

The language and peoples have been previously referred to as ‘Thompson’ (as seen in much of the dated and colonial research).

For this post I will be using the terms nɬeʔkepmx and nɬeʔkepmxcin.

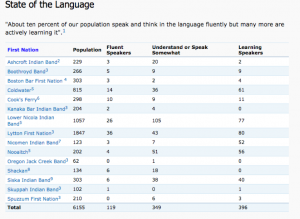

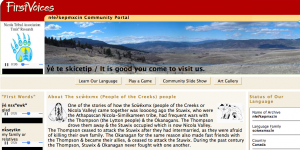

I used the more dated yet heavily documented research to accompany the First Peoples Cultural Council, language map, as well as First Voices nɬeʔkepmxcin portal, to get a sense of where nɬeʔkepmxcin is being spoken and by whom. As well as hearing and learning phrases and words in the language.

I then created a nɬeʔkepmx plant taxonomy classifications chart . As seen below.

The column on the far left is from Nancy Turner’s book “Thompson Ethnobotony: Knowledge and Usage of Plants by the Thompson Indians of British Columbia” (Turner 1990) and the column of the right illustrates examples of the classification system from the First Voices nɬeʔkepmxcin language portal.

| nɬeʔkepmxcin name

(Turner 1990)

|

English name | Examples (from first voices) | |

| Sʔyèp | Large tree | c̓q̓áłp /Douglas fir | |

| mùyx | Tall bushes, small trees | kʷy̓éłps/alder | |

| Sʔqʷiyʔt or

Sʔqʷitèɬp=éɬp

|

Berry fruit bearing

Plants/bushes |

sq̓ʷítéłp/ berry

sq̓ʷoq̓ʷy̓ép/ Strawberry

|

|

| q’əc’ | vine | clematis | |

| Sʔtuyt=úym’xʷ | Low, herbaceous broad leaved plant, “low economic importance” (turner 1990) | ||

| Sʔp’áq’-m | flowers | sp̓áq̓m/ flowers

tokʷłetqn/arnica

|

|

| Sʔyiq-m | Grasses and grass like plants of dryland area | x̣ás x̣ast/sweet grass

|

|

| qʷzém | Mosses and moss like plants | Nʔqʷzem=úym’xʷ/tree moss | |

| q’ámes | Mushroom and tree fungus |

|

Within nɬeʔkepmx culture, sc’òlseʔ has a vast amount of uses, such eaten as a fresh berry, as well as made into a tonic and used for treating irritated eyes, shellfish poisoning, clearing of the skin, cleansing the liver and removing toxins from the blood, arthritis, as well as considered an emergency food when no other berries were found, the root or bark are made into a dye for baskets and food harvesting materials. Once I began to graph and research the many uses of sc’òlseʔ I came across a rich amount of language related to the plant and its uses.

As I was beginning to understand through my research, the role of plants in nɬeʔkepmx culture is incredibly important as was expressed through a huge vocabulary list related to the plant. Looking into the language of this plant, I was able to see an entire culture, a culture that is still very much here. Due to large and varied territory of the nɬeʔkepmx peoples, there are at least 120 different plant species recorded for use, and along with those plant names, comes place names, traditional uses, harvesting practices, recipes, and huge verbs lists, al recorded in nɬeʔkepmxcin.

The reason I was curious about researching sc’òlseʔ(Tall Oregon grape) is because during my time studying to become a nutritionist about 5 years ago, at the Canadian School of Natural Nutrition, here in Vancouver, we were being educated about the medicinal properties of Tall Oregon Grape, as well as how and when to recommend it to clients during nutritional consultations. And although it was taught to us as an alternative medicine, i.e, as an alternative ‘anti biotic, or anti-inflammatory, to be used instead of the dominant and conventional Western medicinal approach, somehow made this particular group of students think their shit didn’t stink, it was spoken to from an incredibly Western colonial framework. Looking back, I remember feeling uncomfortable that we were being trained to profit and ‘educate’ clients about a plant that I knew had to have a very deep and rich connection to the people whose land it grew.

I find the colonial constructed idea of ‘alternative’ health and wellness to be one the most problematic, and colonial areas I have ever encountered as a settler student. It can often dangerously romanticize Indigenous TEK through the the settler fantasy of an “imaginary Indian” (Daniel Francis 1992) trope, perpetuating historicized stereotypes,

or as I experienced in my nutrition program, the complete erasure of any Indigenous presence connected to this knowledge.

The fight against the attempted erasure of Indigenous presence was an incredibly powerful theme of Tuesday’s media share. Whether through maps, as seen in Shoukia’s project, or revitalizing an ‘extinct’ language in Mat’s project, or podcasting about a colonial town, silenced of Indigenous histories as articulated by Salome. People are not only acknowledging Indigenous presence and ongoing resilience but creatively working to create space and honour it.

The entire time I was studying Oregon grape and other medicinal plants in this nutrition program, Indigenous; presence, land , or knowledge was never once mentioned. Nor was the continued resilience of Indigenous culture acknowledged, and not once was the reason this knowledge of these medicinal plants and foods still in existence so much as addressed. And sc’òlseʔ like most of these Indigenous plants, are sold in every health food store in Vancouver.

I recall my instructor at the time, highlighting the locality(the hottest word in nutrition,) of Oregon Grape, and its abundance right here in Vancouver, but never once was it mentioned who’s land this was we were being encouraged to forage on and profit off of. I understand that perhaps that particular teacher might not have known the current territory they taught on, nor the languages spoken, but I feel it is crucial they start to.

“I find it difficult that Vancouver has this identity now as this international cosmopolitan center that has many cultures, which it does, but there’s no recognition that we’re all guests on Coast Salish lands”

-Cree, metis scholar and educator Kamala Todd, 2013.

This small pamphlet or handout would be shared with anyone interested, and of course offered to nɬeʔkepmx community, as well, invited to be edited in every way. Perhaps once seen by nɬeʔkepmx community, I could send it into the First nations Health Authority, who potentially might be interested to see or include sc’òlseʔ in their medicinal plant fact sheet. And last but not least, if it was again given a go ahed by community I would love to offer the information to the ever colonial, Canadian School of Natural Nutrition ( I just went to their website for the first time in like 6 years and immediately crashed my head into my keyboard, fuck its ridiculous.)

The intent of the information would be to encourage readers to understand, as Todd says “We are all guests”. (Todd 2013) As well, I would hope this pamphlet would encourage students there to think about the reason these plants and their knowledge are still here is a direct result of the continued resilience of Indigenous peoples within BC who never gave up their lands, languages, political structures, laws, food sovereignty, and to practice their culture, and to negotiate and maintain their rights under such brutally oppressive legislations from the Canadian Government. And as Kristen Dowell speaks to in “Vancouver’s Aboriginal Media World” the assertion of visual sovereignty works by ” articulating the long standing connection that Coast Salish people have with the land in Vancouver and by repositioning Vancouver as an Aboriginal city.” (Dowell 2013).

The reason I wanted ot reflect on this project in this post is because I thought the FNHA’s way of producing their information was an incredibly powerful and important form of Indigenous visual sovereignty, as outlined in Kristen Dowell’s book, Sovereign Screens: Aboriginal Media on the Canadian West Coast (Dowell 2013), in which Dowell defines Visual Sovereignty as “the articulation of Aboriginal people’s distinctive cultural traditions, political status, and collective identities through aesthetic and cinematic means”(Dowell 2013).

The FNHA’s Traditional Food Fact Sheets acknowledge the continued resilience of Indigenous food sovereignty, languages and cultural health within Indigenous communities both urban and rural, through visual means, which is systematically absent from a broader settler colonial framework of health and wellness in Canada.

Resources:

- Nłeʔkepmxcin FirstVoices Archive. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://maps.fphlcc.ca/node/1600

- Nłeʔkepmxcín. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://maps.fphlcc.ca/nlakapamux

- Nłeʔkepmxcín language vitality (n.d.). Retrieved October 14th, 2016, from https://www.ethnologue.com/language/kwk

- Turner, N. (1990). Thompson Ethnobotony: Knowledge and Usage of Plants by the Thompson Indians of British Columbia.

- Turner, N. J. Keeping It Living: Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America : Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America. (2000). Vancouver, Canada: Gibson Library Connections. Retrieved from http://www.ebrary.com

- Turner, N. J. (2014).Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge : Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America. Montreal: MQUP.

- Anderson, E. N., Pearsall, D. M., Hunn, E. S., Turner, N. J., & Ford, R. I. (2011).Ethnobiology

- Oregon grape. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://wildfoodsandmedicines.com/oregon-grape/

- Oregon Grape. (n.d.). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://lfs-indigenous.sites.olt.ubc.ca/plants/oregon-grape-tall-dull-and-creeping/

- E-Flora BCDistribution Map Mahonia aquifolium (tall oregon-grape). (n.d.). Retrieved October 27th, 2016, from http://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/eflora_maps/index.html?sciname=Mahonia%20aquifolium&BCStatus=yellow&synonyms=%27Berberis%20aquifolium%27,%27Berberis%20aquifolium%20var.%20aquifolium%27&commonname=tall%20Oregon-grape&PhotoID=19779&mapservice=VascularWMS

- Thompson, L. C., & Thompson, M. T. (1996).Thompson river salish dictionary: Nłe?kepmxcín. Missoula, MT: University of Montana.

12. First Nations Health Authority //. (n.d.). Retrieved December 08, 2016, from http://www.fnha.ca/

13.Francis, D. (1992). The imaginary Indian: The image of the Indian in Canadian culture. Vancouver, B.C.: Arsenal Pulp Press.

14.Maskegon-Iskwew, Ahasiw. (2003). Transference, tradition, technology: Native new media exploring visual & digital culture. Banff, Alta.: Walter Phillips Gallery Editions

15. Dowell, K. L. (2013). Sovereign screens: Aboriginal media on the Canadian West Coast. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

16. Hanna, D., & Henry, M. (1995;2014;1996;). Our tellings: Interior salish stories of the Nlha7kapmx people. Vancouver, B.C: UBC Press

David Gaertner

December 19, 2016 — 11:57 am

Great post, Annie. I love to see the continued synergy between Daisy’s course and mine. She and I may have to co-teach something at some point… You do a lovely job sharing this story in an engaging and challenging manner and the details are very well laid out and easy to follow. You have found a very strong voice this term and your blog writing just gets better and better. Great work!