Inquiry Blog Post #4

Our most recent task in my UBC course was to research library projects in developing nations and answer the following questions. It was humbling and inspiring reading!

How are library projects in the developing world creating new literacy opportunities and expanding access to the internet and information databases?

In my research, I found many libraries in the developing world that are improving internet access for their patrons and teaching them a wide-ranging variety of literacy skills including reading, ICT and digital literacy, data literacy, media creation skills, civic participation, health literacy, entrepreneurship and employment skills, and the navigation of public services. Many of these libraries carry out their projects with the support and funding of international NGOs whose mission is to help libraries expand their services as a key part of economic development. For example, IREX is an international organization that is funding library projects around the world, including literacy app development in Ethiopia, the ICT training of librarians and the donation of ICT equipment in Uruguay and Peru, and the training of a group of health volunteers in Tanzania in data literacy (on- and off-line) to help inform and improve local decision-making regarding HIV and AIDS (Vanderwerff).

Testing a literacy app in Ethiopia

The International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) also supports a large number of library projects in the developing world. For example, they fund library-hosted ICT workshops for women in Nepal, and ICT training for female farmers in Uganda, helping them gain better access to information on weather, markets and crop prices. They have also partnered with the Ulaanbaatar Public Library and the Mongolian National Federation of the Blind to build recording booths and teach volunteers how to create, edit and produce audiobooks (IFLA).

How can they best move forward to support the local needs of their communities?

Libraries in the developing world face many serious challenges, especially with regard to bridging what the United Nations calls “digital divides.” Though the UN has set universal access to ICT and the internet as one of its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), there are still great differences in access and skills acquisition between men and women, urban and rural communities, high- and low-skilled workers, and private and public schools (UNCTAD). Though mobile networks now cover 94% of the world, only 35% of the global population is connected to the internet (UNCTAD; World Literacy Foundation). In many areas where there is broadband, it is too slow or unreliable to handle sophisticated web content. Overall, especially in remote or rural areas of the developing world, there is still inadequate access electricity and reading material of any kind (on- or off-line) (UNCTAD). This has contributed to 750 million adults world-wide not knowing how to read (Wall Street Journal). Women’s lack of literacy and ICT access is especially poor due to patriarchal attitudes and family pressures (OECD; Singh). Finally, while NGOs focussed on supporting libraries can be very helpful, they can sometimes bring with them a special set of challenges, such as “solutions” that don’t take into account the local language or culture, or erratic or unsustainable funding (Erickson; Ro). UNCTAD warns that while ICT development in the developing world is absolutely necessary, it may also lead to exacerbated literacy and economic inequalities if not done in a way that consciously tackles these divides.

To address these challenges, libraries in the developing world are employing the following strategies:

- Campaigning for improved access to electricity and broadband in remote locations (UNCTAD)

- Mounting targeted campaigns for women’s education, literacy development, and civic and economic participation (OECD; Singh)

- Offering programs and resources developed by and for girls and women (IFLA; OECD; Singh)

- Developing programs and resources that are grounded in local language and culture (Bibliothèques Sans Frontières; IFLA; Vanderwerff; World Literacy Foundation)

- Developing new funding models (e.g. public/private partnerships) that allow for some outside funding but retain local control (Erickson)

- Developing programs that use mobile technology (Bibliothèques Sans Frontières; Ro; Wall Street Journal; World Literacy Foundation)

How might mobile devices assist in this endeavour and what new affordances do they bring to the developing world that will allow them to provide greater and more democratic access to information, unfiltered and uncensored?

The advantages of offering library and information services via mobile devices (laptops, tablets and phones) are numerous. People who were cut off from vital information about health, public services, economic opportunities, and elections due to location, transportation, technological or gender issues could have their lives changed. Marginalized people can access banking, loans, insurance, employment and market information, increasing family savings, entrepreneurship and income. The OECD argues that access to a mobile phone has a greater positive impact on women and the poor in developing countries than international aid. Low-cost phones with extended battery life are especially effective because mobile networks are easily available from almost all locations, they offer privacy, they require only occasional access to electricity for recharging, and they can be programmed to accept voice-commands for people whose writing skills are poor (OECD).

Another strategy using mobile devices is to provide rural and remote libraries and people with specialized tablets that come either pre-loaded with digital libraries, or have access to low-cost digital library subscriptions accessible through mobile networks. Susan Moody of Worldreader (a partner of UNESCO) notes that in the developing world, access to reading material can be a huge challenge. Having a tablet that can access a library from a remote area gives people new reading opportunities and helps them improve their literacy (Wall Street Journal). Sun Books (an initiative of the World Literacy Foundation) is another organization that provides school libraries and teachers with tablets that can access digital libraries; their readers also include a solar panel so that electricity is not needed for recharging. Both organizations provide materials in local languages, written from the perspective of the local culture. Having these readers fills in gaps in locations where educational materials or leisure reading may be hard to come by and supports the development of literacy among adults and children.

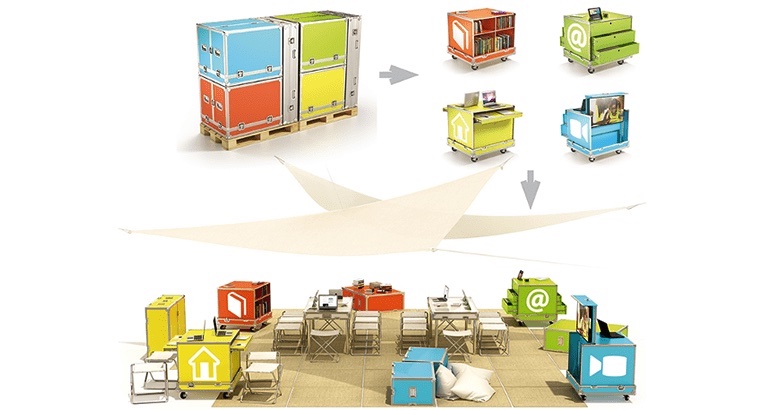

A third strategy is one demonstrated by Bibliothèques Sans Frontières (Libraries Without Borders), an organization that sets up mobile physical libraries in underserved communities around the world, including refugee camps and disaster zones. Bibliothèques Sans Frontières (BSF) recognizes that access to information and communication technology is vital for people who have recently been traumatized and need to contact their families, access public services, and find employment. They have developed a resource called the Ideas Box which contains everything needed to set up a miniature community library in an area with few resources. Within twenty minutes of opening an Ideas Box, a BSF facilitator can offer a generator (for electricity), a satellite internet connection, 25 laptops and tablets, books, games, arts and crafts supplies, cameras, a large display screen, sound equipment and a stage. Resources are customized to the needs of the community (adults and children) and may include materials on trauma recovery, conflict resolution, and creative arts. They hope to include whatever can help people process their experiences, combat boredom and stand in during a suspension in children’s education (Bibliothèques Sans Frontières).

Another organization that provides a mobile library is the Rural Libraries and Resources Development Programme in Zimbabwe. They provide donkey-drawn library boxes filled with books, computers, and phone recharging stations, powered by solar panels on the box’s roof. Though their reading materials are mostly donated, and therefore often do not take the local language or culture into account, the materials still fill a gap in remote areas difficult to reach by car and are helping teachers increase literacy rates (Ro).

All of these projects are excellent demonstrations of how digital technology, and creativity when faced with difficult local situations, can provide opportunities to increase literacy and decrease poverty and gender inequality.

Resources

Bibliothèques Sans Frontières (Libraries Without Borders). (2018). 4 years of the Ideas Box. https://www.bibliosansfrontieres.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/4-years-of-Ideas-Box-av-liens-2.pdf

Erickson, C. A. (2013, February 27). In Central America, community-minded libraries become community funded. American Libraries Magazine. https://riecken.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/ALA-article.pdf

[Harnessing the donkeys in preparation for going on the move] [Photograph]. (2017, October 2). Literary Hub. https://lithub.com/on-the-move-with-the-donkey-powered-mobile-libraries-of-zimbabwe/

[Ideas Box opened] [Composite photograph]. (n.d.). Libraries Without Borders. https://www.librarieswithoutborders.org/ideasbox/

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). (2016). Access and opportunity for all: How libraries contribute to the United Nations 2030 Agenda. https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/hq/topics/libraries-development/documents/access-and-opportunity-for-all.pdf

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2018). Bridging the gender digital divide: Include, upskill, innovate. https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf

Ro, C. (2017, October 2). On the move with the donkey-powered mobile libraries of Zimbabwe: A look at the country’s rural libraries and resource development program. Literary Hub. https://lithub.com/on-the-move-with-the-donkey-powered-mobile-libraries-of-zimbabwe/

Singh, S. (2017, March 24). Bridging the gender digital divide in developing countries. Journal of Children and Media, 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2017.1305604

UNHCR / Charlotte Jenner. (2019, September 13). [Boys reading tablets] [Photograph]. HEA (Learning Series). https://medium.com/hea-learning-series/innovation-profile-libraries-without-borders-ideas-box-fdab491cc05f

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021). Digitalization offers great potential for development, but also risks. SDG Pulse. https://sdgpulse.unctad.org/ict-development/

Vanderwerff, M. (n.d.). Libraries for development. IREX. https://www.irex.org/project/libraries-development

Wall Street Journal. (2014, April 23). How mobile devices drive literacy in the developing world [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3NqU6gqsTM&t=44s

[Women and girls looking at a tablet] [Photograph]. (2016, April 15). Ethiopia Reads. https://www.ethiopiareads.org/2016/04/05/app-testing-irex-code-ethiopia/

World Literacy Foundation. (2020). The power of libraries. https://worldliteracyfoundation.org/the-power-of-libraries/

This is a comprehensive and well-researched post. I agree that solutions to global literacy issues need to be mindful of not exacerbating inequalities. I also agree that it is inspiring to learn more about the creative and innovative ways that people are working to address these issues.

What do you think is a better initiative to promote reading in developing countries? Do you think that investing in books and shipping them to Africa is the answer? Or do you believe that investing in tablets is the best solution? I am so torn. One one hand, I understand that tablets can hold more information but I worry about the lifespan on these tools. On the other hand, holding physical books is pretty magical! But, this limits your selection and can be very expensive.

Hi, Michelle.

I hear what you’re saying. A paper book doesn’t break down (usually!) after 5 years, or have its subscription run out. But I think I still come down on the side of the tablet over books shipped in from outside, especially if they hold resources written in the local language that take the relevant culture into account. If they’ve also been designed for the physical surroundings (e.g. solar-powered, rugged construction, software that will age well) then I think tablets are the best bet. It would be great if the tablet company or organization could also offer low or no-cost repair as part of the service. Mostly, I think I would want children to see themselves represented in what they read. I think that would have the greatest impact on their motivation to read (reading is for them!) and their literacy skills. But, man, this is a tough question!

Andrea