INTRODUCTION

Welcome to our lecture! Today we’ll be discussing the Rarámuri of the Eastern Sierra Madres in Chihuahua, Mexico. You may have heard of this group in popular media, the best-known being the novel Born to Run by Christopher MacDougall (2009), which brought to light the Rarámuri’s unmatched talent for ultra-running. Because of this book, and subsequent media, athletes around the world covet the Rarámuri diet and exercise regime to improve their own performance. But as we’ll soon find out, there is much more to this “running people” than their legendary mileage. Before we get started, one thing to note is that information about the Rarámuri is scarce, and our group was hard-pressed to find ethnographic information about the group because of their characteristic reclusivity. But this is part of why we think their history, culture and foodways are so compelling.

THE BASICS: HISTORY AND BACKGROUND

Some refer to the Rarámuri as the “Tarahumara,” which is the result of a (remarkably poor) mispronunciation of Spanish colonizers in the 17th Century (Barrett 5). The group prefers Rarámuri, which means, “Running People,” or “foot-runner,” in their language. Speaking of their language, it’s also called Rarámuri, has many dialects, and is still spoken by most Rarámuri today. However, due to increasing urban connectivity, the extent of the use of the language is diminishing (Caballero 227-228). It is an oral language, which is one of the many reasons that ethnographers have had a hard time tracing the group’s history.

The Rarámuri’s history with colonizers helps explain their reclusivity. In the 17th Century, when Spaniards and Jesuit missionaries tried to impose reducciones on the Rarámuri, they encountered a resistance that they hadn’t expected. One major point of contention between the missionaries and the Rarámuri was the production and consumption of tesgüino, a corn beer that holds ritual significance for the Rarámuri. Missionaries saw tesguino ceremonies as contrary to church teachings they were trying to impose, and several bloody rebellions ignited over it (Arrieta 12-13). The Rarámuri refused to be controlled by the missionaries, and in order to survive, they fled to the remote depths of the almost-inaccessible Copper Canyons and Sierra Madres (Barrett 10). The Rarámuri have lived in the Copper Canyons and surrounding area ever since. This is part of why ethnographic information on the group is so scarce; the Rarámuri stick to their isolated mountains and canyons to avoid the encroachment of outside interests. Thanks to their resourcefulness and reclusivity, the tesguino ritual, like almost all of their pre-colonial traditions, have been preserved to this day despite those early efforts by missionaries and continuing globalization (Barrett 11).

The State of Chihuahua, also called the Sierra Tarahumara/Sierra Madres.

Source: http://www.mpm.edu/research-collections/anthropology/online-collections-research/tarahumara

Copper Canyons

Source: https://www.worldnomads.com/explore/north-america/mexico/copper-canyon-guide

FOODWAYS

The way the Rarámuri interact with and use their food reveals a lot about who they are as a people. This includes how they eat, what they eat, and the styles of cooking they use. A group’s foodways have the potential to tell a deep story and this holds true for the Rarámuri. Their unconventional diets focusses on non-meat products and first foods.

The “traditional” Rarámuri diet has historically been heavily based on corn and beans, as well other fruits and vegetables (McMurry et al. 1704.) They also consume eggs, fish, and game meats but they do not eat these proteins often and, when they do, they only eat it in small amounts (McMurry et al. 1704). Their diets are centred around natural foods and produce that must have the ability to grow on the rough terrain of the Sierra Madre Mountains. Plants aren’t just for consumption but serve multiple purposes for the group. It is believed that the Rarámuri interact with 1000 different plants and their uses include turning the plants into textiles, building material items, and concocting medicines and drugs, with some of these used in ceremonies (Camou-Guerrero et al. 261). This exemplifies the ability of the Rarámuri to adapt and take advantage of the resources that are made available to them, even in the challenging environment of the Sierra Madres.

First of all, let’s address the running, and how it relates to Rarámuri foodways. Although the Rarámuri do not consume large quantities of meat, their unmatched running capabilities come from a long history of “persistence hunting,” whereby hunters target a prey species and then chase them on foot over long distances, literally running them to death. The Rarámuri obtained a part of their sustenance this way, to supplement their vegetarian diets, so the activity of running is not just for physical fitness, but has long been central to their foodways. Some Rarámuri even report persistence hunting in their communities as recently as 2011 (Lieberman et al.). Additionally, the Rarámuri are spread out across the extremely mountainous Sierra Madre, and their remote communities are mostly connected by trails, not roads (Lieberman et al.). So if they want to communicate or barter, they must cross long distances by foot; thus, running is also a form of communication and connectivity.

Staple Foods

Let’s talk about 3 main staple foods of the Rarámuri: agave, corn, and chia. You might associate agave with tequila; however, for the Rarámuri, this plant is mostly utilized as a food for the people to eat (Bye et al. 86.) The usual method of cooking agave is through baking it in a pit, and the parts of the plant that are consumed are the heart and leaf base (Bye et al. 86). The process of cooking agave is said to be gendered, as men are often the ones that partake in it (Bye et al. 86). The reliance on agave as a food item is most prominent when food sources kept from the last growing season begin to diminish, but the rain for the next growing season, the summer time, has not happened yet (Bye et al. 87.). Another way the Rarámuri use agave in their foodways is by grinding the heart and mixing it with tortilla dough made of corn, which we’ll talk about next (Bye et al. 88).

Agave plant

Source: https://cdn.britannica.com/18/127018-004-B3B579E0/Caribbean-agave.jpg

Corn is another staple food of the Rarámuri and many Mesoamerican groups, especially ones that originate from Mexico, since corn abundantly grows in this area (Perales and Golicher 1). Two main foods come from corn, and these are tortillas and tesguino. Tortillas have been a Rarámuri staple food for a long time and, to this day, constitutes the main food they consume. The tortilla that the Rarámuri make is unique, as it is more unrefined than our store-bought tortillas and thus, more filling and nourishing (Goshen 2015). Now let’s talk about the drink that caused so much contention in the 17th Century: tesguino. Tesguino is a beer made from corn, and the consumption of it holds great cultural importance, as we’ll soon discuss. The process of making tesguino involves first fermenting the corn with a local grass seed called basishuari (Kennedy. 622.). The drink takes seven days to make but despite the lengthy process, it needs to be consumed within a short time-frame after its creation, typically 12 to 24 hours (Kennedy. 623).

Traditional Tarahumaran Tortillas. Tesguino in a cup surrounded by corn.

Sources – (Tortilla): https://www.ecoalternativetours.com/top-ten-reasons-sierra-tarahumara/

(Tesguino): http://saboramexico.com.mx/sabor2/index.php/bebidas-mexicanas/519-bebida-tesgueino-del-norte

Chia is the final notable food item to consider when talking about the Rarámuri. This seed is consumed because it is quite beneficial for athletes. Indeed, it has been termed a “superfood,” and can be found in most health food stores today. The Rarámuri are known as runners and they often carry chia seeds with them because they are small enough to bring along. They are also quite filling and when they are in water, the chia seed can expand up to nine times its size, making it a more substantive and hydrating snack (Goshen 2015).

Food Security

When it comes to food security, the current situation for the Rarámuri is a cause for concern. While many parts of Mexico experience problems with this, the Rarámuri are known as “Mexico’s poorest citizens,” so this issue becomes magnified even more (Cordero-Ahiman et al. 2). Children within this group are susceptible to malnutrition (Monarrez-Espino et al. 5). This has led to a reliance on government services that provide food to families in need, such as the Mexican Government for Tarahumara Children (Monarrez-Espino et al. 5). We’ll talk more about how the Rarámuri interact with these services in our section on globalization.

RITUALS AND RELIGION

Running and The “Ball Game”

The athletic gifts and ethic of the Rarámuri have made them legendary in the Western running and fitness community. Everyone in the Rarámuri community—no matter gender or age—is expected to be in athletic shape and be able to do physical labour, especially given the tough, varied environment in which they live (INPI). The Rarámuri’s attitude and talent for running has remained a spiritual, religious, social, and ethical part of the community, and one that is instilled

A nighttime scene of rarajapuri, undoubtedly fuelled by tesgüino

Source: https://www-journals-uchicago-edu.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/doi/full/10.1086/708810

in its members from an early age (INPI). One of the Rarámuri’s most important running-related cultural practices is rarajipari, or the “ball game.” This is a footrace whereby teams run around a long and difficult circuit, using their toes to kick a wooden ball until the predetermined number of laps is reached, a team uses their hands, or a forfeit occurs due to exhaustion (Goshen). Hands are not allowed to be used in the game and long games of rarajipari can last up to 150km. The women’s version of this race is called ariawete. These “ball-games” aren’t just “games.” They hold spiritual significance for the Rarámuri. Guiding the ball over the lengthy race replicates navigating the complex, chaotic journey of life. Further, the extreme endurance, which sometimes lasts overnight, may induce a heightened state of awareness and out-of-body sensation (Lieberman et al.). Before the race, the wooden balls are soaked in a mixture of chiles and lechuguilla—a distilled form of agave tequila—, to “cure” them of any evil spirits, an example of how agave, a staple food, holds spiritual significance as an integral part of Rarámuri foodways (Lieberman et al.). The race also provides a chance for communities to come together, place bets, and partake in tesguino, which is consumed by runners and spectators alike and is a critical part of this ceremonial sport.

Tesguino

Through ceremonies like running, and via the tesguino drink, the Rarámuri attempt to honour their gods and deities. They believe their gods were the ones that granted them the tesgüino, and thus, it is their duty to show gratefulness and humility for the corn beer by using the energy it gives them (INPI). Running, dancing, and working are seen as a spiritual method of connecting with the gods, just like praying in other religions (Kennedy). The act of giving an offering is also a popular method of giving thanks, as an act of sharing the food or item with the gods that provided the energy via tesguino to attain the food (Kennedy). Several Rarámuri legends involve people using tesgüino to solve problems and collaborate with the gods (INPI). The tesgüino is believed to have helped with the creation of the sun, moon, and their distinct movement patterns, and is therefore part of Rarámuri origin stories and cosmology (INPI). As Barrett observes, “In the myths and folk tales of the Tarahumara, this ceremonial corn beverage serves not only as the lubricant of the mechanism of the Tarahumara existence, but also as the spark of life in a version of the creation story, as remuneration for cooperative labor, as a prize for suitors of a young lady, as a product of mundane daily activity, as a bartered ítem in a running competition, and as a motivator and companion for hunters in the field” (149).

While dance and music are prevalent in Rarámuri communities throughout the year, their biggest and most exciting celebrations are undoubtedly the Tesgüinadas festivals (INPI). These festivals tend to be held during the winter months as a celebration of the previous harvest and as a time to wish for a plentiful harvest in the coming season. Dancing and playing instruments constantly occur during these festivals, and the tesguino is continuously consumed as a source of energy (Kennedy).

The fascination for the Rarámuri’s legendary running has started a tourist industry in the community where the staple drink of the Rarámuri, the tesgüino, is quickly being exported to other Mexican communities and across the world in the process of globalization (Kennedy).

Religion

Despite their reclusivity and rejection of the 17th-Century attempts by missionaries to assimilate them, the Rarámuri drew a lot of influence from the Catholic religion but made it their own (Arrieta 21). While the Rarámuri don’t necessarily believe in saints or the Ibrahimic definition of Jesus and the Father, they do use similar methods of praise and spiritual customs to connect with their equivalent deities (INPI). Almost every equivalent of the Catholic divinities can be found in the modern Rarámuri religion, with a specific deity serving as a stand-in for Jesus and another for Mary (INPI). While inspiration was taken from the Catholic missions that have come to the Chihuahua region, the Rarámuri religion is still extremely distinct and very representative of the daily living that the Rarámuri go through. How can this relate to our class keyword, syncretism?

GLOBALIZATION

Now that we have delved into the history, culture, and foodways of the Rarámuri, it is important to highlight the ways in which the Rarámuri maintain agency in various aspects of their lives, including education, tourism, political participation, and economic development. We will also discuss the threats that the Rarámuri face during the epoch of globalization.

While remaining heavily reclusive in nature, as mentioned in the beginning, the Rarámuri lend great importance to close family, community, and ancestral ties as a means of maintaining identity and agency in a rapidly changing world. Their location allows them to remain reclusive and practice these values without much interruption, although there have been numerous attempts to capitalize the Copper Canyon region (which we will get into later). The Rarámuri have been affected by globalization, of course, but they have taken active efforts to not engage in it and are extremely selective in who they allow into their communities. The means through which the Rarámuri face and handle globalization in their own unique ways were the most compelling and intriguing part of studying this group for us. Now, let’s get into it!

Agency in Education

A crucial aspect of carrying on traditions, rituals, or knowledge is providing education. Since the Rarámuri hold such deep values in family and community, education by learning from parents or other elders in the community is a given. The concept of experiential learning and interaction with the environment around them helps Rarámuri children grow to learn the land in the same ways their elders did; this is especially relevant for learning the plants and animals of the Copper Canyon (Wyndham 99). Experiential learning to support ethnobotanical knowledge helps Rarámuri children learn that over 400 plants are used for medicine, 300 plants are included in local diets, and 100-200 plants are used for weaving, building, and other uses (Bye 89). Currently, many Rarámuri children also attend elementary school, either run by the Mexican government (primarily in Spanish) or by Jesuits (Spanish and local Rarámuri language). At the government-run school, there is a focus on Mexican/Mestizo education whereas the Jesuit-run school typically has Rarámuri teachers and parent support (Wyndham 89). This is a great example of the Rarámuri maintaining agency in the sense that they can choose the education their children receive.

Agency in Tourism

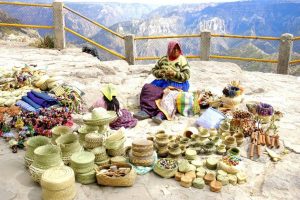

Mexico operates as a capitalist society, like most of the world, and the Mexican government has tried to integrate the Rarámuri into the capitalist economy to aid the state of Chihuahua, specifically the Copper Canyon region (Krutak). While some Rarámuri are willing to semi-integrate themselves into the tourist markets, many are against it to maintain their agency, culture, and local economy. The interest in tourism within this region stems from the spread of development in the 1980’s, as there were massive global shifts and new interconnections (Nash 1981). The main way some Rarámuri have become involved in tourism is through the production of handicrafts to be sold in high volume tourist areas, particularly made by Rarámuri women. Some involved enjoy the financial benefits it has provided to their families and have abandoned their agricultural practices to focus on weaving artisan pieces (Krutak). In saying this, we can suggest that capitalist systems and development have somewhat transformed Rarámuri culture. However, this mostly dependent on an individual/family choice, as not all Rarámuri agree or take part in the tourism sector. This reflects the agency and choice that the Rarámuri loosely hold onto today in spite of numerous attempts to infiltrate the Copper Canyon region to satisfy ethnic tourists from the West and the Mexican government in exploiting indigenous identity and culture for profit.

Another example of the Rarámuri exercising their reclusive nature and agency is through media tourism. As featured in the film Goshen and book Born to Run, the Rarámuri welcomed these two groups to do media features that provide outsiders with an “inside view.” It is not usual for the Rarámuri to allow just anyone in considering their location and hesitancy towards outsiders, and they are very selective, hence the limited number of sources like these.

A Rarámuri woman sells her work at a tourist site

Source: https://www.wildernessinquiry.org/itinerary/Mexicos-Copper-Canyon/

Agency in Foodways and Agriculture

Because of the Rarámuri’s hard-to-reach location and tendency to remain independent as a community from outsiders (the Rarámuri call non-indigenous outsiders “chabochi,” meaning children of the devil), most Rarámuri agricultural processes and staple foods have been maintained (e.g. native corn species compared to widely spread GMO corn). Before the Spanish infiltration, many Rarámuri practiced rancheria-style farming, which Krutak defines as a “subsistence strategy relied on small-scale agriculture,” including the three sister crops as well as hunting, gathering, and even sometimes fishing where groups were dispersed across wide areas rather than being centred in one village (26). Somewhat affected by the reducciones, the Rarámuri took some Western agriculture techniques, including livestock and agricultural technology, then integrated these methods into their own indigenous agricultural practices (Krutak 26). The Rarámuri even adopted the Catholic Ritual Calendar that aligns with their own ceremonies and prime maize season (Krutak 28). Krutak suggests that these acts by the Rarámuri constitute appropriating Catholic factors and reclaiming their culture as a means to increase their agricultural productivity, therefore reflecting their agency.

Two Rarámuri men using indigenous agricultural techniques for preparing a field for small-scale crop production (Goshen Film)

Agency in Economic Development, Economic Opportunities, and Threats

The Rarámuri have effectively adapted to the rapidly changing world that exists today and have found ways to maintain agency while using external economic development to benefit them. An example listed above included Rarámuri women having agency in taking part in the production of arts and crafts products that they then sell in tourist markets. As discussed in the film Goshen, we see that during race rituals and other indigenous traditions or celebrations, Rarámuri community members have the opportunity to win prizes from others including homemade leather shoes used for running (still currently used today!), food, or clothing items. This exchange of goods exhibits a non-monetized way of maintaining stability and agency (and is reminiscent of the Quechua barter markets!). For agricultural development, some Rarámuri have turned to a local seed company that supplies them with non-GMO and local seeds to aid in food security. Some Rarámuri people, typically men, also go abroad to the US for seasonal work to send remittances home. Another interesting way the Rarámuri have taken part in sharing their culture or opening up their community to outsiders is through the video game development partnership on Mulaka, a game where the player plays a Rarámuri shaman and must navigate the Copper Canyons. This game was made possible through a partnership with Chihuahua-based gaming company Lienzo and the Rarámuri people themselves. Creating a video game to showcase parts of their culture to those outside of their world, deciding what is included and how it operates is a unique way the Rarámuri have interacted with outsiders (Woolbright 199).

As mentioned in the Agency in Tourism section, the Rarámuri are not newcomers to attempts at having their land jeopardized, particularly by the Mexican government and other foreign actors such as big corporations. Efforts to exploit the Copper Canyon region for its natural resources are a constant threat. Beginning in 1910-1920 during the Mexican Revolution, the government sorted communities into communal living spaces and “economic units” called ejidos (Krutak 24). This action allowed Mestizos to claim Rarámuri land and permitted big companies to come in and begin deforestation processes. The harsh exploitation of Sierra lands affected both Rarámuri and Mestizo communities living in the region and caused an outward migratory flow to other places in Mexico and even the US (Krutak 24). Wyndham also noted the severe resource exploitation which resulted in soil erosion, less rainfall due to deforestation, and overall made land more competitive even though it was Rarámuri land (88). Other more recent threats have included the proposal to build an airport, narcotics traffic and other cartel presence that causes violence in this region, potential pipeline developments, and the continuing negative effects of climate change (Acosta). We can suggest this is part of the reason why the Rarámuri make a strong effort to be more reclusive.

RECIPE

To finish off this lecture, we invite you to join us in cooking a “traditional” Rarámuri recipe, adapted from Chef Ana Rosa Beltrán del Río, a renowned chef from Chihuahua. As we mentioned above, the Rarámuri sustain a mainly vegetarian diet, but with some meat here and there, as in this recipe. Note: we used moose meat from Avery’s recent harvest, but any meat can be substituted if you don’t have pork (as written in the original)!

Check out this short Instagram Reel we made, which includes the steps for del Río’s recipe! Accompanying the post is a song called, “Tarahumara Matachine Dance,” a song adapted from the matachine tune, which was introduced by Jesuit missionaries in the 17th Century (Sheehy 12). This is yet another way that the Rarámuri have taken some aspects of external influence and made them their own.

You can view our Reel and you can see the original recipe here!

Lecture by (with blog links):

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arrieta, Olivia. “Religion and Ritual among the Tarahumara Indians of Northern Mexico: Maintenance of Cultural Autonomy Through Resistance and Transformation of Colonizing Symbols.” Wicazo Sa Review, vol. 8, no. 2, 1992, pp. 11–23, JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1408992.

Barrett, Joan Parmer. Tarahumara Transcripts Face to Face with Modernity: An Intertextual Approach. 2017. Texas A&M University, dissertation.

Bye, Robert A., et al. “Ethnobotany Of The Western Tarahumara Of Chihuahua, Mexico: I. Notes on the Genus Agave.” Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, vol. 24, no. 5, 1975, pp. 85–112. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41762295. Accessed 12 Nov. 2020.

Caballero, Gabriela. “Choguita Rarámuri (Tarahumara) Language Description and Documentation: A Guide to the Deposited Collection and Associated Materials.” Language Documentation & Conservation, vol. 11, 2017, https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=T002&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=SingleTab&hitCount=1&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm¤tPosition=1&docId=GALE%7CA522210347&docType=Report&sort=RELEVANCE&contentSegment=ZHCC&prodId=HRCA&pageNum=1&contentSet=GALE%7CA522210347&searchId=R3&userGroupName=ubcolumbia&inPS=true.

Camou-Guerrero, Andrés, et al. “Knowledge and use Value of Plant Species in a Rarámuri Community: A Gender Perspective for Conservation.” Human Ecology : An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 36, no. 2, 2008, pp. 259-272.

Cordero-Ahiman, Otilia, Eduardo Santellano-Estrada, and Alberto Garrido. “Food Access and Coping Strategies Adopted by Households to Fight Hunger among Indigenous Communities of Sierra Tarahumara in Mexico.” Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 2, 2018, pp. 473.

Goshen. Directed by Dana Richardson and Sarah Zents. Filmhub, 2015.

INPI , Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas. “Etnografía Del Pueblo Tarahumara (Rarámuri).” Gob.mx, 19 Apr. 2017, www.gob.mx/inpi/articulos/etnografia-del-pueblo-tarahumara-Rarámuri.

Kennedy, John G. “Tesguino Complex: The Role of Beer in Tarahumara Culture.” American Anthropologist, vol. 65, no. 3, 1963, pp. 620–640. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/667372. Accessed 26 Nov. 2020.

Krutak, Lars F. Selling the Copper Canyon: Tourism and Rarámuri Socioeconomics in Northwest Mexico, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2009, pp.26-29, Accessed 11 November 2020

McMurry, Martha P., et al. “Changes in Lipid and Lipoprotein Levels and Body Weight in Tarahumara Indians After Consumption of an Affluent Diet.” The New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 325, no. 24, 1991, pp. 1704-1708.

Perales, Hugo, and Duncan Golicher. “Mapping the Diversity of Maize Races in Mexico.” PloS One, vol. 9, no. 12, 2014, pp. 1-20.

Rivera Acosta, Juan Manuel. “Leave us alone, we do not want your help. Let us live our lives; Indigenous Resistance and Ethnogenesis in Nueva Vizcaya (Colonial Mexico).” Social Anthropology Theses, 2017, pp. 97-118, Accessed 11 November 2020

Sheehy, Daniel. “Review of Indian Music of Northwest Mexico: Tarahumara, Warihio, Mayo (Música Indígena Del Noroeste de México); Rarámuri Tagiara: Music of the Tarahumar.” Ethnomusicology, vol. 23, no. 2, 1979, pp. 352–54. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/851476.

La Sierra Tarahumara y su gastronomía milenaria. http://laviejaguardia.com.mx/noticias/la-sierra-tarahumara-y-su-gastronomia-milenaria. Accessed 22 Nov. 2020.

Woolbright, Lauren. (2019). “Slow Violence in a Digital World: Tarahumara Apocalypse and Endogenous Meaning in Mulaka” Ecofictions, Ecorealities, and Slow Violence in Latin America and the Latinx World, 2019, pp. 199, doi: 10.4324/9781003001775-11.

Wyndham, Felice S. “Environments of Learning: Rarámuri Children’s Plant Knowledge and Experience of Schooling, Family, and Landscapes in the Sierra Tarahumara, Mexico.” Human Ecology, vol. 38, no. 1, 2010, pp. 87–89. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25652764. Accessed 27 Nov. 2020.