Maps are definitely one of those concepts that are hard to confine with one definition. In fact, I think that all of the different definitions that we discussed in class are not only relevant, but necessary in building a wider perspective with which we can view maps. Corner says that maps are “a fantastic cultural project, creating and building the world as much as measuring and describing it”, while Turnbull says “Maps are theories and they are socially and culturally constructed.” These definitions are indeed true in the sense that maps hold tremendous cultural significance and also biases, respective of whoever the maps were created by and who they were created for. A simple example is how different geographical regions throughout history had centred themselves in their worldview, or how sizes of certain regions are exaggerated while others depicted much smaller than we now know them to be. The definition I will be focusing on today is that of Berry, who claims that maps are “a form of graphic representation that takes as its frame of reference the physical environment, which it normally treats from an aerial perspective, with some attention to verifiable spatial distribution. Furthermore, a map relies on a combination of codes—particularly an iconic code—to construct that environment.” And particularly, I will be looking at what kind of coding is visible in the Chikyū bankoku sankai yochi zenzusetsu map from 1790.

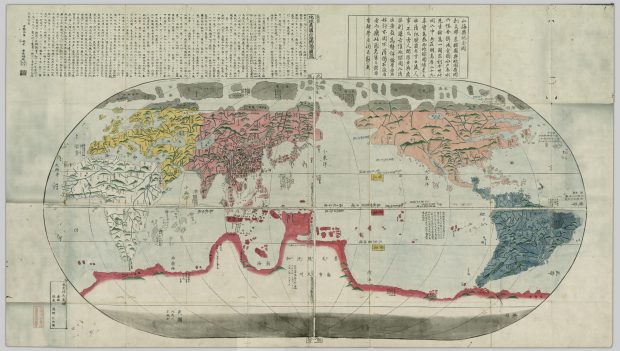

Most of the coding that we can see in this map is quite straightforward. First of all, I am not quite clear on whether this map would be considered topographical or topological. The map does not necessarily denote the different gradients of elevation as topographical would suggest. On the other hand, it also does not resemble the sort of symbolic representation that we associate with topological maps. That being said, the first bit of coding that is very obvious in this map are the mountains. I would assume that the green inverted W-shapes scattered across the land masses are meant to denote any regions that are mountainous. Do these generic symbols of elevated regions mean that the map is topographical? I am under the impression that legitimately topographical maps show much more detail in changes in elevation, while the mountains in this map seem to be more symbolic. That being said, this sort of coding is very effective for the reader, in that most likely anyone who saw this map, having no prior knowledge of the coding system, would recognize the green shapes as mountains. Another clear example are the blue lines that run through the land masses. These seem to denote rivers, and once again, most people would likely arrive at this conclusion upon first viewing this map.

Now, the more interesting bits of coding have to do with the visible biases(?) that we can see in the map. First of all, how do we know which sections of the map are meant to represent land masses and which are meant to be ocean? We know that the colored areas are land, but this is largely because we already have a pre-existing image of the world map in our minds. If not, we could potentially perceive the colored regions to be oceans, that the green hills are islands, and that the blue lines are simply common routes taken by boat. Furthermore, why are the different sections of said land colored differently? Using the knowledge we have about the world and from maps we’ve seen previously, we can assume that this is to separate the world into geopolitical regions. But is there a reason for the specific colours? That I can not answer for sure.

Finally, the most intriguing aspect of the “coding” that I saw in this map comes from the respective sizes of certain areas. Most blatantly, Japan is centred in the Map, which is to be expected. What is more interesting to me however, are the absolutely massive sizes of Europe and the Americas in this map. Particularly interesting to me, was that Europe and Africa were drawn to be relative in size, which we know is not actually the case. It may be important to note that this map was a copy of one brought to Japan by Matteo Ricci. To me, it seems as though there many have been a political agenda behind the depictions of certain areas being drawn larger than life, while others not so much. But then, why is Antarctica drawn to be literally a third of the entire earth, and a short boat ride away from the southern tip of Africa?