Hello all,

In out ASTU class this week we began with a discussion of Saal’s article on Johnathan Safran Foer’s novel “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close”. From here we moved on to discuss Judith Butler’s novel “Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?” which is the main theoretical lens which Saal uses in her unpacking of Foer’s text. Not surprisingly, the blogs this week were in discussion of the questions raised by both Saal and Butler, and their applications in our community and our world.

In all the blogs this week, there was one strong motif of “us” vs “them” which really stood out. This idea of “us” vs “them” stems from Butler’s argument against our socially developed, western, mono-narrative understanding of the grievability of some lives over others. To quickly explain; Butler argues that due to our physical bodies vulnerability to destruction we are socially conditioned into fearing others that we do not see ourselves in (due to culture, values, media, etc.). These people’s lives, however similar to us in their own vulnerability, we see as “ungrieveable” due to our specific frames of “us” and “them” developed by our social nature. We see their lives as “that [which] cannot be mourned because it has never lived, that is, it has never counted as a life at all” (38). Throughout the blogs this thinking is taken apart in many different social circumstances to evaluate the problem and complications associated with this type of thinking, and how we may come to be more cosmopolitan in how we understand our place in the world.

If that made no sense to you, check out Nicola’s blog, her explanation of Saal and Butler is great, and she goes on to expand this idea of the “other” to language. She argues that how we speak about, and convey this “other” (or “them”) is reminiscent of our specific frame of thinking and therefore solidifies our separation of their humanity from ours. To help break out of this dichotomy of us and them, we must think about how and what we are saying, and what message this reinforces. Similarly, Kaveel in his blog talks about the connection of Butler’s argument of different “Frames” to Shazad’s article on interpretive communities. He says that these communities, being created through social interaction also act as ways in which Butler’s “frames” are shaped. These in turn shape our understanding of “them” and affect the ways that we act.

While the two blogs above discuss the frames (and the creation of these frames) used to shape Butler’s idea of “us” and “them”, I’d like to move to two blogs which present examples of this type of thinking in our community and internationally. Kihan, in her blog applies Butler’s lens to that of the c̓əsnaʔəm Musqueam burial ground incident in 2012. She argues that perhaps, there is a “mainstream Canadian view of Indigenous lives as “ungreivable””, which was present in the mistreatment of Musqueam burial ground, and still is in Canadian society. She also provides another example of this distinction of “them” in her community: The 26th Annual February 14th Women’s Memorial March for the missing and murdered women of the downtown eastside. Kihan argues that events such as this, and the 100 day vigil following the c̓əsnaʔəm Musqueam burial ground incident in 2012 are examples of social events that work to break down the barriers set up by our frames of grievability inside our community, city and our country.

While the classes’ blogs were mostly focused on the negative aspect of creating a “them”, Tzurs blog takes the discussion of Butler’s frame type thinking in a unique direction. While Kihan’s blog focused on two examples of “them”, and one example of the “us” type thinking (South Memorial Cemetery) in commentary with the “them”, Tzurs blog focuses on the negative results of including some people, or nation-states in this “us” type thinking. He argues that America’s foreign policy of mutual alliance with Saudi Arabia (which he says means including them in the “us” category) is negative in this thinking of “us” and “them”, as the Saudi’s long history of continuing human rights abuses do not fit with Americas values, and therefore it is dangerous to include them as part of who we frame as “us”. He justifies Americas decision to include them because “the primary factor for classifying someone as “us” or “them” is whether or not they consolidate power for our side.” A number of questions pop into my head following this example, which I think is a controversial, but also a creative flipping of situations that Butler might find intriguing.

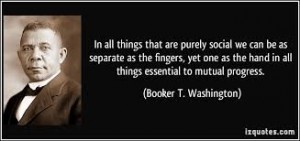

To make these questions of “whose life is grievable?” even more confusing and complex, I’d like to apply this thinking to something we discussed in Human Geography in order to think about the message of these blogs as a whole. In my discussion for Human Geography, we talked about social inequality of sweatshops in terms of global wealth distribution and how we should live inside this western, relatively rich frame with that issue in mind. Should we buy products produced in sweatshops, even if it seems everything is produced by them now? I think this issue can easily be viewed from Butler’s idea of “us” and “them” discussed I the blogs. Ignoring arguments that sweatshops improve people in certain situations lives, I would like to be able to give an ultimatum of saying no, and include them in a cosmopolitan understanding of people around the world. However, as Ina says in her blog, in our daily lives that idea of “us” and “them” is present everywhere, from our relationships with family and social circles, to those distinctions we make in an international context. So realistically, I think those people working in sweatshops we ignorantly and even unconsciously distinguish as in the “them” category, by buying things in massive quantities produced by their pain, for our material gain. With this in mind, how do we change our frame of mind if it is unconscious, and built into the very system we live in and are socialized to? How do we break out of this distinction of “us” and “them”? This is what Butler writes a whole book on, and so many of the blog this week were about, so I don’t have a definitive answer quite yet. However, like Nicola and Kaveel suggest, through the way we think, speak and interact with others this distinction is created. Therefore, we must break out of our ignorant and unconscious actions within this frame, and take on a conscious state of mind in which we analyze the way we act all the time to determine our actions effect on how we view others. This in its essence is the cosmopolite existence which Butler strives for, but which is intricately hidden within our daily social lives by the cloudy frames that have been placed in our minds and that we view the world through. To conclude, I’d like to leave you all with a quote from Booker T. Washington: