Hello readers!

Term 2 has started already, and we’ve already started buckling down in class. Recently, in my ASTU course, we’ve finished reading Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran Foer.

The book was intriguing to read, and a little different from what I am used to seeing. Many other students in my ASTU class has also found it an interesting experience, which led many to write about it in their blogs.

Joseph, has fascinatingly written about the use of Beatles’ songs and references throughout the book. He shows readers how song choices and their lyrics match the events in the novel, and the emotions felt at those times.

Others have focused on Oskar, a child and one of the narrators within the novel. Mostly, these people have explored how Oskar works to overcome his grief over his father’s death in the terrorist attack of 9/11. Isaiah examines Oskar’s attempts to seek closure by searching for the lock of the key he had found when going through his father’s things. Isaiah points out that Oskar’s journey to find the lock was an attempt “to stay close to his father just a little bit longer.” Indeed, Oskar acknowledges this within the novel, stating that looking for the lock “let [him] stay close to him” (304). In this way, we can see that Oskar’s journey could have been him seeking for a way to alleviate the grief he felt for his father’s death and absence in his life.

To extend this examination of Oskar seeking closure and trying to overcome his grief, Alex states that he believes that Oskar “serves as a motif or symbol for the thousands of people who lost friends and family” in the events of 9/11. Elizabeth examines the suddenness of death, and how deeply such tragedies can affect people in grief. She also makes note that during such times, there is a regret for not letting those lost know how much they mean to you. Characters within the novel are similar in this respect, because they wish to have let their loved ones know that they loved them before they died. Oskar and his grandmother are such examples. This aligns with Alex’s belief that Oskar represents the people who have lost their loved ones. It is common for those who lost someone to wish they had told their loved one what they mean to them. Oskar (and his grandmother) also wish to have been able to do that.

However, is Oskar only just representing those who are grieving for their losses after 9/11? What would happen if Oskar’s father had died in other circumstances? Ryan expands on this thought, looking into possible outcomes to Oskar’s father having died in an event like a car crash.

Despite this, it is still unclear if Oskar truly is a representation of those grieving in the aftermath of 9/11. Is the fact that the setting of this book was placed at such a time and that Oskar has such a personal connection to it what makes Oskar a representation of it? Or is Oskar, in parallel with his grandparents, meant to represent all who have lost loved ones in tragic events?

– Sandra Maglanque

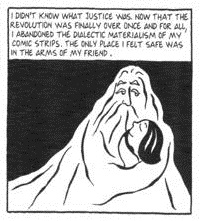

I especially love the panel immediately after Marji had cast God out of her life.

I especially love the panel immediately after Marji had cast God out of her life.