Hello fellow bloggers and curious readers,

This week I’m the class blogger so it’s my responsibility to summarize and find connections in my classmates most recent blogs. The blogs this week drew some impressive connections and had very intellectual insights.

In class we recently read the graphic narrative “Persepolis” written by Marjane Satrapi, this book is a common theme amongst the blogs. We also recently read and analyzed Hilary Chute’s article, “The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis” the connections that people drew from this article and Persepolis maintained a common theme in the blogs. The most prevalent theme, in regards to “Persepolis”, was the illustration style and the use of art as a literary tool. Joseph, Martin, Paolina, and Kennedy all tackled the topic of either black and white, or a different element brought into play through illustration.

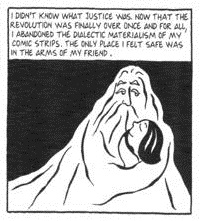

In Paolina blog she discusses how the graphic novel genre opens up a wide variety of interpretations for the reader. She writes on the unique style that adds a new level to the story by illustrating what there are no words for. She discusses the levels of interpretation that are allowed when illustrations are brought into the story, asking the important question “How much influence does the genre of “graphic narrative“ have on our subconscious view and interpretation of narratives though its visual and discursive storytelling?” Paolina also discusses how pictures provide a foundation for a unique style of thought processing, comparing pictures to “soil” that we are able to build and grow from.

Joseph’s blog was distinct in that he did not dwell too extensively on Persepolis, instead he draws connections from the theme of black and white to other directions of thought. He wisely compares black and white to good and bad. Drawing the connection that we, as a society, always attempt to interpret situations as good or bad, black or white, and how these rigid mentalities can cripple us and cause deep anxiety. He discusses perfectionism and how it leads to thoughts of intense anxiety, realizing that if we always seek to reach an extreme end of the spectrum of black and white, we will become burdened with an unrealistic responsibility on ourselves that is both unlikely, and unattainable.

I found this train of thought both eye-opening and humbling. In these early stages of University, when everyone is trying to figure out exactly how much effort they should be putting into each aspect of life, it’s easy to get weighed down by self-inflicted expectations. The realization that there is no perfect can bring people back to the present and enable us to actively engage ourselves in all parts of the University experience.

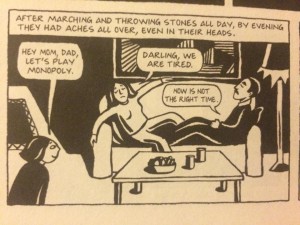

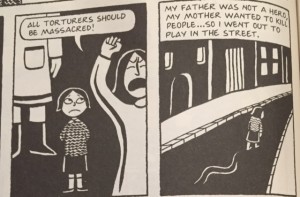

Both Martin and Kennedy discuss the topic of violence through abstract illustrations in their blogs. Martin writes about how the use of black and white creates an abstraction to the violence in the book by denormalizing it. He talks about how putting violence in colour in comic books makes it seem like just a normal everyday occurrence. When you put the violence in black and white and use abstract drawing styles, however, it makes the violence seem unsettlingly surreal and otherworldly. Kennedy touches on this as well, saying that Satrapis graphic work provides a “wow factor” that would not otherwise have been portrayed without the use of images.

Olivea also brings up denormalization through graphic images. She draws a comparison between Persepolis and the pulitzer prize winning graphic novel “Maus” by Art Spiegelman. In Maus, Olivea tells us, the author uses cats and mice to replace Nazis and Jews in an effort to show how absurd and unfathomable violence was in the holocaust. The use of minimization in Maus and Persepolis is similar in that both graphic narratives use this art form to induce interpretation and emotion from the readers.

Clara manages to construct a blog about Persepolis that focuses primarily on culture, specifically “symbolic culture” and the role that it plays in Persepolis. She draws from her personal experience with symbolic cultural and how it is active in her life. She discusses how symbolic culture is prevalent all over the world, but the difference is in material culture, “The difference in “symbolic culture” between where I live (Canada, part of the “western” world) and the Islamic state in Iran manifests itself visibly by a difference in “material culture””. Clara brings up the parallels between material culture differences numerous times in her blog, recalling time in Persepolis when Marji would be disciplined or persecuted for her progressive beliefs and lifestyle

Reading all of the blogs this week I was struck by how lucky I am to be in a class with so many advanced, and progressively minded people. It is really impressive to see how fast and adeptly people pick up on themes in the book, and the connections that people make to either their personal lives, or the lives and experiences of others. What I drew from the weeks blogs was a pronounced feeling of respect and humbleness towards my classmates. The ability to ask questions and critique culture and society is such a powerful ability, the way that Joseph was able to question the massive topic of good and evil in a single blog post was very powerful. The way that Clara was able to draw relations from her personal life experiences to that of a war torn Iran is quite a feat. It is very easy to get comfortable living on the west coast of Canada in a wealthy city at a prestigious university amongst friends and teachers. But through this comfortable bubble we must remember how important it is to always question, to always draw parallels and to always be curious and critical.

Have a wonderful week everybody, I hope you all continue to enjoy the euphoric bliss of studying for mid-terms

Isaiah

I especially love the panel immediately after Marji had cast God out of her life.

I especially love the panel immediately after Marji had cast God out of her life.